Anatomy of a toxic lab: Global Biodiversity, Ecology & Conservation at Yale University [With critical update Apr 5, 2023 about Yale's long prior knowledge of the abuses]

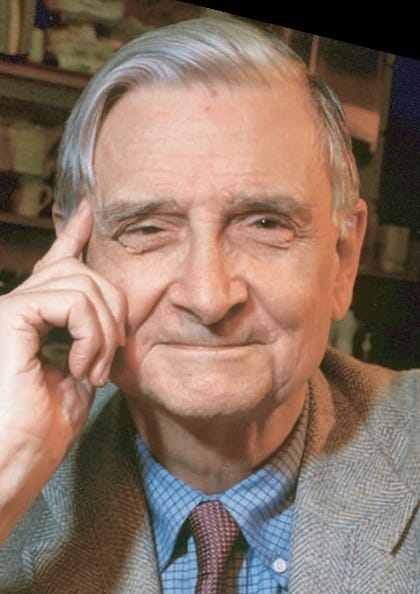

A lab run by ecologist Walter Jetz, and heavily funded by the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, has long been plagued by bullying and dysfunction. Yale has taken little serious action so far.

Introduction.

Beginning in fall 2015, when I was still a correspondent for the journal Science, I began reporting on what might be called the dark side of science: The abuses that powerful academics all too often visit upon students and young researchers. These abuses, which include sexual harassment and bullying but often take more subtle forms, have made the lives of thousands of would-be researchers miserable, driving some out of science entirely.

As I will discuss more below, they are not just due to the individual failings of the lab and institution directors who abuse their powers, but are symptomatic of an academic culture based on extreme power differentials and hierarchical structures, often infused with a profoundly anti-democratic spirit inimical to the spirit of free inquiry which scientists are supposed to live by.

After Science and I had a parting of the ways in early 2016, I continued this reporting for The Verge, Scientific American, and other publications. But the limitations of trying to convince editors to cover #MeToo and bullying issues—especially when a lengthy investigation was required to uncover and confirm many of the abuses—made me decide in the end that I had to go completely independent if I was going to be able to do the reporting I felt was required. I explained this decision in a September 2019 article for the Columbia Journalism Review, which is now a bit out of date but I think still very relevant.

I am now in my ninth year of doing this reporting. At times it has been thankless: I have been sued for defamation (unsuccessfully), had my reputation smeared with lies and other slander, and at times gotten thoroughly depressed at just how widespread the abuses are (some of them involved my own scientific heroes.)

At the same time, my reporting has involved dozens of investigations, and a significant number of those have resulted in either the termination or forced resignation of the abusers in question. They have also brought widespread attention to my reporting.

This past February, I was contacted by a former postdoctoral researcher at Yale’s laboratory of Global Biodiversity, Ecology & Conservation, led by ecologist and evolutionary biologist Walter Jetz. The lab, which is largely funded by the E.O Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and inspired by Wilson’s influential yet often controversial conception of these issues, has for many years been a magnet for young researchers in these fields. It has been under Jetz’s direction since 2016. Jetz, who is German but has spent most of his career elsewhere in Europe and in the United States, has also been scientific chair of the Wilson foundation since 2018. Many young scientists have come into the lab full of excitement about the research they might be able to do there; but as I was to learn, in many cases those hopes soon turned sour, due to a combination of bullying, micro-management, and alleged unethical conduct by Jetz, all in the context of a toxic lab atmosphere that drove many young researchers to leave earlier than they had intended.

One former lab member put me in touch with another, and soon a number of researchers had either contacted me on their own or responded to my messages. In the end, seven former members of the lab, most of them former postdocs, talked to me in detail about their experiences. What follows is based on their stories, although—to protect their identities, because these are fairly small and specialized research fields and fear of retaliation by Jetz or others is strong—I have kept the details vague enough so that any attempts to guess who spoke to me would only be pure speculation.

As I will discuss shortly, Yale University is fully aware of the toxic atmosphere in the Jetz lab, and has tried to mediate between lab members and Jetz in various ways. At the same time, the university has sought to keep the problems quiet, claiming that is to protect the young researchers and other staff. But in my discussions with sources, it was clear that their highest priority, after suffering from often very stressful experiences while in the Jetz lab, was to warn other scientists who might be thinking about working there what they might have to confront should they make that choice.

That, too, is my main motivation in publishing this report. And I hope, before I am done, that readers will understand that this is not some kind of tempest in a teapot that has little relevance for anyone outside Yale or outside science. How our academic institutions operate, and how they treat scientists and other scholars eager to learn and contribute to society, is critical to the survival of our planet and our democracy, both of which are in grave danger.

“Every meeting with Walter was uniquely stressful.”

Toxic labs are many, and each is stamped with the personality of the scientist at the top. In talking to former members of the Jetz lab, however, I was struck by the near uniformity of their experiences, especially their many negative ones.

An overall theme was Jetz’s belittling attitude even towards postdocs who had come into the lab with quite a bit of prior research experience. One former colleague, who gave me permission to quote liberally out of their comments, described this in detail. I am quoting at length because this reflects what so many others told me.

“I only maintained any grip on reality thanks to the (unusually) large number of other postdocs working with me at the time (4 or 5 of whom were hired at the same time as me). This espirit de corps allowed us to sanity check each other, vent, plan collaboratively, and provide each other with positive feedback. The latter is something that Walter is particularly lacking on. Effectively we (to a greater or lesser extent) negated Walter’s ability to gaslight each of us by verifying expectations between each other. Many of our group conversations, as well as my one-on-one talks with colleagues were commiserating about Walters inability to communicate fairly or empathetically or set expectations rationally. In particular Walter will give you one set of goals and then demand an entirely different set of outcomes at a moments notice, often being disinterested in the expected results and instead focus on your inability to complete something entirely different concurrently and unexpected. Every meeting with Walter was uniquely stressful and he would interrogate you mercilessly leaving no doubt that you were inadequate and responsible for his displeasure that ‘nothing was being achieved’ or ‘deliverables were well behind.’ He has an ability to completely destroy any self confidence or sense of accomplishment by being unimaginably cold and scathing in explaining your lack of ability and productivity. This was regardless of my attempts to set firm and more achievable targets. He was disinterested in hearing that the work we were each undertaking was more than many entire labs produce in a year and he expected it in a couple of months. It took me a good 24 hours to recover from each meeting.”

Another former postdoc agrees that the biweekly meetings were “a roller coaster of anxiety.” Like many others in the lab who already had earned their PhDs from other institutions, this scientist thought they would “have a lot of freedom” to design their own research strategy and carry it out. Instead, in nearly every meeting, Jetz would lay out “a list of tasks to be done” and then, in following meetings, demand a detailed accounting of what had been accomplished. This researcher and others told me that “there was a lot of yelling” by Jetz not only at the lab meetings, but also in individual meetings.

(The overall atmosphere, complete with the yelling, was similar to that in an Australian ancient DNA lab I investigated at the University of Adelaide, led by ancient DNA pioneer Alan Cooper; in that case, the university fired Cooper after the story went public.)

Nearly all of the sources told me that Jetz showed very little interest in the individual careers of the researchers in his lab. Rather, no matter what research projects had brought them to Yale, Jetz was largely concerned with the data they could contribute to one of the lab’s key projects, the Map of Life, a global database of planet and animal species. Moreover, some told me, Jetz pressured them to collect data from other researchers not affiliated with the lab so they could be plugged into the database.

This imperative led to ethical issues in a number of cases. Early on, Jetz had gained a reputation in the biodiversity community for using the data of other scientists without permission. According to some lab members, this behavior has continued at least up until recently, as Jetz, in his apparent determination to make the Map of Life as complete as possible, instructed some researchers to “strip” data from the Web sites of other scientists and refused to consider signing data-sharing agreements with potential collaborators.

Several former lab members told me that their efforts to persuade Jetz that such data stripping was unethical, and that outside researchers should at least be offered co-authorship on papers resulting from this data, either fell on deaf ears or encountered stiff resistance from the senior scientist.

The Jetz lab in crisis: Accusations of racism against E. O. Wilson.

The Jetz lab, as a major project of the E.O. Wilson foundation, not surprisingly lived in the shadow of Wilson and his ideas about biodiversity, which have been challenged by other scientists (I will not be able to get into this complicated subject here, other than to flag it for readers who are interested in pursuing the issues; Wilson’s ideas about preserving half of the earth are contested by some other scientists. )

But anyone who follows Wilson’s scientific ideas must also contend with the legacy of his 1975 book “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis,” which brought claims from critics that Wilson was at best a biological determinist and at worst a racist (one of the most interesting critiques was written by the late anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, and a group of scientists at Harvard and other institutions launched a blistering critique of Wilson’s ideas that has resonated over many decades.)

Nevertheless, both Wilson and his supporters fought hard, and usually successfully, against the accusation that Wilson was personally racist. That defense, however, fell apart shortly after Wilson’s death, when two groups of researchers, digging into archives, found clear evidence that in fact Wilson was an enthusiastic supporter of the late scientific racist J. Philippe Rushton, whose ideas about race and intelligence had long been notorious.

I wrote about this episode myself in this newsletter a little over a year ago. As I said then:

This new evidence matters greatly, because over all these years the conceit of Wilson and his defenders has been that they were champions of scientific truth, and their critics were driven by politics and ideology. Indeed, the term “race realism,” used by Rushton and other scientific racists as a bludgeon against anti-racists and an attempt to depict them as cowards who cannot face what science allegedly tells them, can now clearly be seen as evidence of Wilson’s own attitudes and biases (Wilson was no shrinking violet in defending his ideas, as even the hagiographic retrospectives make clear.)

As might be expected, many members of the Jetz lab were sent into a crisis of anguish over these revelations, since the lab was so closely associated with Wilson and his legacy. And most of the sources I talked to saw Jetz’s reaction to these concerns—and to the desire by many lab members to discuss them in collegial meetings—as a serious examples of his apathy, if not disdain, for the welfare and concerns of the younger scientists working under him.

Jetz did circulate the Wilson foundation’s statement on the revelations, in which the organization quickly distanced itself from the clear racism Wilson had displayed in his correspondence with Rushton. But several former lab members told me that he tacitly discouraged discussion of the racism allegations, leaving the younger researchers to discuss it privately amongst themselves rather than in the entire group.

At the same time, Jetz sent the entire lab a series of emails “that got progressively unhinged,” as one postdoc put it, describing the accusations as “fringe or extreme views.” (I have been provided with the email thread.) Jetz argued, in essence, that sociobiology did not have any relationship with race science, and that in any case sociobiology had nothing to do with the research agenda of the lab.

While at times in the email threads Jetz seemed to be inviting discussion of these issues, I was told by several colleagues that—due to what they called Jetz’s “passive-aggressive” approach to any disagreements in the lab—they did not feel comfortable doing so.

Yale gets involved, tries to mediate, with limited success.

By 2020, several lab members had made their unhappiness known to the Yale administration, both formally and informally. Around that time, the university began a review of the “climate” in the Jetz lab. This effort was initially carried out by Yale astronomer Debra Fischer, who was formerly a dean of academic affairs in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. According to sources, a number of lab members met with Fischer, and Jetz was also asked to meet with Fischer so he could be “coached” on ways develop a more convivial lab atmosphere. Other university officials also got involved in the meetings, and later, Yale psychologist Margaret Clark.

(Both Fischer and Clark declined to discuss the matter with me, citing confidentiality concerns.)

Former lab members report that after these meetings things would get better for a time, but Jetz would then relapse into his prior behavior. As of this writing, according to sources, the lab climate remains tense and stressful for many scientists currently there, many of whom are just trying to get their work done and “keep their heads down,” as one put it to me.

The Yale administration refuses to discuss the problems in the Jetz lab, or even to admit there are any. Karen Peart, Yale’s director of media relations, asked me to publish the university’s statement in its entirety, which I agreed to do:

“Yale is committed to preserving the confidentiality and integrity of its complaint processes. This commitment helps encourage our community members to participate and is consistent with state and federal privacy laws. Accordingly, we do not comment on or even confirm the existence of specific disciplinary cases.”

The problem with this statement, of course, is that a number of former members of the Jetz lab have talked with a reporter, precisely because they are not confident that Yale will actually take any decisive action to either solve the oppressive climate in the Jetz lab or get rid of Jetz, a tenured professor who brings a great deal of grant money and prestige to the university. Unfortunately, this leaves it to members of the lab to try to warn possible recruits to stay away, which they have been doing over the past several years (I am told that the Jetz lab’s bad reputation has now spread far and wide.)

In other words, Yale’s lack of transparency, typical of the wagon-circling most institutions engage in when bad behavior could mean bad publicity, actually exacerbates the problem and ends up protecting no one except the institution itself.

One former postdoc summarized the problem in a particularly eloquent way, and I would like to close with what they had to say. The bottom line is that the problems in the Jetz lab are, as this colleague says, “a symptom of a broken system.” (I also recommend “How bullying becomes a career tool,” published in Nature Human Behaviour last year.)

“…if there is nothing else that I would like to stress in the Jetz saga it is this: Walter is a symptom of a broken system. The academic model as it stands prioritizes and rewards exceptional output at any cost. It rewards those who are willing and able to claw their way over the bodies of colleagues and employees to achieve results, a pile of bodies provided thanks to an astounding oversupply of incredibly talented and over-qualified people willing to throw themselves into the breach at the likely non-existent prospect of achieving success in their own careers. As long as the machine continues to produce, there are too few consequences and too great a reward to mistreating others, this will continue. In fact the system selects for this. The more successful you become, the fewer tangible rewards there are for being a more empathetic and humane researcher – as Walter’s prestige has ascended, so have the number of people willing to risk a large known cost for a small chance of reward. I think that if we ever expect to replace the Walters with more humane leaders we will need to tackle the innate structures and reward feed-backs that academia imposes on itself. Until then the system will continue to fail the vast majority of us who try to achieve what is considered success, and while it will allow Walter to succeed at the detriment of others, it has ultimately failed him also.”

Important update April 5, 2023

Since publication of the original post, sources directed me to Stephen Stearns, emeritus professor at Yale who was intimately involved in earlier developments concerning the promotion of Walter Jetz. Dr. Stearns has kindly prepared a timeline of events, which I have posted below with no edits of any kind (with his agreement and permission.)

The timeline, which I would invite other Yale faculty and researchers to confirm, makes it very clear that the university ignored many warnings about Jetz’s behavior beginning no later than 2011. I will leave it to Dr. Stearns, at the end of his narrative, to give his own interpretation and why and how this happened.

This annotated timeline of Walter Jetz's promotions at Yale was provided by Stephen C. Stearns, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Emeritus, Yale University.

At Yale tenure and promotion works like this:

1. The department solicits multiple letters from independent experts, evaluates the case, and sends its recommendation to the tenure and senior appointments committee for the biological sciences, the Divisional Committee.

2. The Divisional Committee evaluates the case and if its ruling is positive - the critical step - the case is sent to the joint board of permanent officers (JBPO), a body consisting of all of the full professors in the faculty of arts and sciences.

3. In the JBPO, a positive vote of 2/3 of those present is required to approve the appointment, with a quorum of at least 41 needed to make the decision valid. Normally this is a rubber stamp of the decision of the Divisional Committee. Failure at this stage is rare.

4. If the vote of the JBPO is positive, the case goes to the Yale Corporation for final approval. Failure at this stage is exceedingly rare, although conceivable.

At each stage of the process, only those at or above the rank of the person under consideration have the right to vote.

Fall 2008: Jetz applies for a tenure-track position, is offered the job, gives up tenure at UCSD to come to Yale with a promise from the EEB department that he will be rapidly evaluated for tenure. The department promises to recommend him for tenure when hiring him and feels obligated to hold to its promise.

2009: arrives at Yale, sets up his lab, submits his tenure package. The department gathers letters from independent experts evaluating Jetz, which the senior faculty read, together with his tenure package. They meet to vote in Spring 2011

Shortly before they meet, the chair receives a letter from a distinguished professor at Stanford requesting that he not be tenured because he had stolen data from a Stanford graduate student, Cagan Sekercioglu, and published it without acknowledgement. The chair regards this as an unjustified external interference in an internal matter. Most, but not all, of those voting agree. (Jetz later apologizes in print in what appears to be the only public apology he has made:

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(11)00216-8.pdf)

The case proceeds through the subsequent committees with positive majority votes and he is tenured effective July 1, 2011. He is thus tenured before serious concerns about his behavior at Yale surface.

January 2013: Stearns notices that a postdoc in Jetz's group has disappeared from their workplace. On a visit to another university, to which they have moved, Stearns meets and talks with them. They tell him why they left - corrosive atmosphere in the group - and give him the names of several graduate students and postdocs who can provide more information on the abusive environment in his lab. They request anonymity because they fear retaliation. In interviewing those whom they suggested, Stearns discovers that one of Jetz's graduate students has left science completely, going into a career in the foreign service, and that some of Jetz's postdocs report being humiliated in front of distinguished visitors. The spouse of one postdoc describes their time in New Haven as a living hell. Jetz is quoted by a postdoc as saying that they should not have children because engagement with children reduces their productivity. Stearns takes his evidence to the administration, who tell him they are taking over, and he should step back.

Other senior faculty members talk to and support Jetz's graduate students and postdocs, none of whom want to bring complaints because of fear of retaliation by Jetz. Those faculty discuss options for reporting abuse and provide space and equipment for their research. Thus, not all of the senior faculty turn a blind eye to the abuse, although some influential ones do so. One of them repeatedly requests a full review of Jetz's behavior in addition to reactions to particular incidents. No action is taken.

None of the faculty junior to Jetz at the time are involved in the decisions.

September 2014: Jetz requests promotion to full professor, a departmental committee is formed to evaluate his case, and letters are requested. When the senior faculty of the department meet to evaluate the case, Stearns presents his findings and recommends against promotion, pointing out that Jetz had stolen data (as he later admitted), removed graduate students and postdocs from co-authorships previously agreed upon, and kept some of them from entering interesting research collaborations with other scientists. He argued that Jetz had damaged the department and that if he were encouraged to stay, there was a serious risk that he would do more damage. The senior faculty vote to deny his promotion, but one of his strongest senior supporters is on sabbatical and not present for the vote.

Spring 2015: When that person returns, he requests that the department revisit the case. This time, with his strong recommendation, the department votes to promote Jetz to full professor, but the vote is not unanimous. The Divisional Committee, suspicious about the weak support, turns him down. Jetz takes his case to the provost, who writes the department, instructing them that they should not use faculty conduct as a criterion in voting for promotions, only scholarship and teaching. The senior faculty of the department vote again, this time more positively, send it to the Divisional Committee, and the Divisional Committee votes approval, sending it to the JBPO.

Several members of the department are incensed at the provost's letter. Stearns sends a strongly worded written response to the provost and has a private meeting with the president of the university alerting him to the situation. The most senior administration is fully informed of the situation. The only action taken is to refer the matter to committee.

At the meeting of the JBPO, when the senior faculty member, a Jetz supporter, who is standing in for the department chair, absent on other business, makes his presentation, he mis-speaks about the evidence the department had available that might account for negative votes. Stearns rises to correct that misimpression. The JBPO vote does not reach the 2/3 majority required for promotion, a rare occurrence.

Jetz protests the decision and notes that he has not been allowed to respond to all accusations. At Yale any faculty member accused of misconduct is allowed the opportunity for a written response. Jetz writes a clear, eloquent response in which he blames the graduate students and postdocs for their problems and absolves himself. Some faculty believe him.

The provost forms a senior committee to review the accusations, and Stearns provides them with written testimony submitted to the department and leaked to Jetz. It contains one accusation — a single phrase, not a full sentence— to which Jetz had not been able to respond in writing. The provost's committee concludes that his rights had been violated and the case is sent back to the department.

A deputy provost and a representative of the Office of General Counsel (the university's lawyers) visit the meeting of the senior faculty and instruct them that they must vote again. Some found this unusual intervention humiliating. The department votes positively, but not unanimously, for promotion, and the case again progresses through the Divisional Committee and the JBPO, where Jetz's promotion to full professor finally receives approval.

Jetz appears to be the only person in the history of the institution who first failed, then succeeded, at each of the three major stages of evaluation - in the department, in the Divisional Committee, and in the JBPO.

These details of the steps in the bureaucracy of promotion are important because they document that although his bullying and dishonesty were known to the department and to the administration early on and were discussed in detail several times over a period of several years, he was tenured and promoted to full professor—after the department was explicitly admonished by the provost, in writing, that faculty conduct should not be considered in such cases.

How could this happen? Apparently the department and the university value the money he raises in grants and the fame generated by his publications in high impact journals more than the emotional and professional damage done to the lives of graduate students and postdocs. That damage lasted more than a decade and may be ongoing. Administrative procedures are weighted to protect the interests of tenured faculty, who are at the institution for a long time, over the interests of postdocs and students, who come and go relatively quickly.

There are perverse incentives embedded in a competitive academic system that rewards professors for exploiting graduate students and postdocs to increase their productivity and bring money and fame to themselves and their institutions. Where there are tradeoffs between costs and benefits, when the benefits are very large, the costs that will be tolerated are also very large. Cases like Jetz's reveal how costs and benefits are perceived and weighted by university departments and administrations.

Instead of firing him, which might have led him to bring lawsuits and would have generated a lot of negative publicity, the university required that he undergo counseling aimed at changing his behavior. That counseling has been carried out by competent people with good hearts and good intentions for several years. They have intervened strongly. One could ask his current postdocs and graduate students how successful that has been. One might also ask whether the current negative publicity is worse than what might have been generated earlier.

When informed of the initial substack story, the senior faculty who voted in favor of hiring, tenure, and promotion, two of whom have now retired, took no responsibility. Such behavior is both normal and discouraging.

In 2015 Yale began to upgrade its standards of conduct. For example, the current version of the Faculty Handbook contains this paragraph for postdocs who encounter misconduct:

" A Grievance Procedure for Postdoctoral Appointees is available for individuals who believe they have been treated in a manner inconsistent with University policies, or that they have been discriminated against or have been inappropriately disciplined for misconduct. This procedure can be found in University Policies for Postdoctoral Appointments in the Office for Postdoctoral Affairs. Complaints of academic or scientific misconduct must be brought under the “Policies and Procedures for Dealing with Allegations of Academic Misconduct at Yale University.”

The increased emphasis on standards of conduct was at least in part a reaction to the university's experience with Jetz.

Given the publicity the case is now receiving, and the damage done to more than a few young people by not correcting the situation at the time, it is clear that sometimes it is wiser to listen to one's conscience than to lawyers, for eventually truth will out. So far, Jetz — a highly cited and well-funded full professor at a major research university— has reaped the rewards of his bad behavior, those whom he bullied continue to suffer, and those who tried to prevent the damage largely failed.

A thank you to Michael for the reporting and the brave souls who shared their stories to bring the unethical behavior of Jetz to light. I was someone bullied by Jetz as a young faculty member at another institution. A trend that was, and likely still is, common for him. I want to emphasize that Jetz’s toxicity and unethical scientific practices reach beyond his lab. He bullies and belittles junior faculty probing for situations where he can exploit individuals for their data, ideas, and forced collaboration. Beyond individual cases, he influences and gathers scientific output of other researchers in his positions of power through the broader scientific enterprise. He reviews grants for the National Science Foundation, other funding agencies and foundations. He is an editor at multiple high-profile journals and reviews (very harshly with long delays) manuscripts that he later publishes on very similar topics. I no longer submit papers to journals at which he is an editor despite these journal’s statements on confidentiality, because Jetz does not adhere to ethical practice. Not only has behavior like this damaged individual lives and careers, but it has led to a general distrust of our scientific institutions from funders to publishers as they struggle to protect the less powerful or even acknowledge the potential for internal injustices.

Many around the community in which Jetz works have long suspected that his lab would be quite a toxic place. So sad to see that those suspicions are indeed true, and that Jetz’s ego is damaging the careers of young scientists.