Are "conspiracy theories" always wrong?

The term is often used to try to discredit unconventional ideas. But there is a running debate among philosophers, psychologists, and social/political scientists about its proper and improper uses.

Let’s start with some definitions. Here is how Wikipedia defines the term “conspiracy theory:”

“A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.”

Since this definition uses the term “conspiracy,” we must also know what that means. Definitions vary, but a pretty straightforward one can be found in the Cambridge dictionary:

“The activity of secretly planning with other people to do something bad or illegal.”

As often or even normally used, the term “conspiracy theory” is considered pejorative, as indicated in the Wikipedia definition. Most of us, when we think of “conspiracy theories,” probably think of ideas for which there is either little evidence, lots of contradictory evidence, or both. The 9/11 “truther” theory, that the Bush administration (and not Al Qaeda) brought down the Twin Towers to provide an excuse for war in the Middle East, is one; the Alex Jones-associated theory that the killings of the Sandy Hook children and teachers were staged to bolster gun control efforts is another; the old chestnut that NASA faked the moon landings (either to save money or because they couldn’t really pull them off) is a third.

But we know there are real conspiracies, and sometimes the theories to explain them are well supported. Here are some examples, all of which were described one way or the other as “conspiracy theories” but turned out to be true.

Richard Nixon and his aides conspired to cover up hush money payments to the burglars who broke into the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate.

The FBI sent messages to Martin Luther King, Jr. urging him to kill himself.

The tobacco companies had scientific data that cigarettes were harmful but kept it from the public.

Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, conspired with other scientists to hide the fact that he personally wrote and organized a letter in The Lancet declaring that the lab origin hypothesis for Covid-19 was a “conspiracy theory.”

It won’t surprise regular readers of “Words for the Wise” to see this last one included, given that the controversy over Covid-19 origins is a regular feature of this newsletter. Is it really justifiable to throw the term “conspiracy theory” at any idea we don’t happen to like or agree with? Does the term really serve any purpose?

I’ve long been interested in this question. What prompted me to write this particular post was a story earlier this month in Scientific American, “Conspiracy Theories Can Be Undermined with These Strategies, New Analysis Shows.” The article is based on a new study published in PLOS ONE by Cian O’Mahony of University College Cork in Ireland and his colleagues. Sure enough, the study explored what “interventions” are most effective in countering conspiracy theories.

The author of the SciAm story, Stephanie Pappas, described four takeaways from the study: 1/ Don’t appeal to emotion. 2/ Don’t get sucked into factual arguments. 3/ Focus on prevention, before people are exposed to specific conspiracy theories; and 4/ Support education to put people into an “analytical mindset” and teach them how to evaluate information.

Let’s leave aside for now the apparent contradiction between point 2 and point 4 on whether facts are relevant, and the question of whether anyone should be using “interventions” to try to modify what others think. The basic problem here is that the term “conspiracy theory” can include conspiracies that are real and those that are not real. So who decides which is which before the “interventions” begin?

As my first step in this “deep dive,” I followed up with two of Pappas’s sources for her story, Joseph Uscinski, a political scientist at the University of Miami, and Karen Douglas, a psychologist at the University of Kent in the U.K.

Pappas cited a 2022 study by Uscinski and his colleagues finding that beliefs in conspiracy theories have not actually increased over time, using three different studies—one going back 50 years—to arrive at that conclusion. The authors looked at dozens of supposed conspiracy theories, including ones related to Covid-19, such as the belief that the seriousness of the pandemic was exaggerated by political groups that wanted to damage Donald Trump, and the “lab leak hypothesis” itself.

As we all know, both of these Covid-related “conspiracy theories” are still being debated today, including by scientists and other experts. While I personally don’t think the danger of the pandemic was exaggerated, such issues as the effectiveness of vaccines and masks are certainly subject to continued debate, as is, of course, the origin of the pandemic.

But what I found particularly interesting was the study’s listing of 37 other “conspiracy theories” going back many decades. To put it charitably, this list was all over the place in terms of plausibility and likelihood. For example, along with poorly supported (in my personal opinion) theories about fake moon landings, accusations that the AIDS virus was created and spread by a secret organization, and suspicions that Osama bin Laden is still alive, were allegations that Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone to kill JFK, that the “1%” control the U.S. government and economy, and that Donald Trump colluded with the Russians during the 2016 electoral campaign.

This mix of theories with various degrees of likelihood and plausibility suggests to me that the term “conspiracy theory” is so fluid it has little meaning. Indeed, Uscinski sent me another of his papers, “What is a Conspiracy Theory and Why Does it Matter,” which argues that acceptance or rejection of conspiracy theories is almost entirely subjective: “…what is obviously false to one person can be common sense to another” and it “tends in large part to be determined by partisan, ideological, and other priors.”

I pursued this with Uscinski in an email exchange, in which we did not entirely agree that the list mixed apples and oranges in terms of the likelihood certain conspiracy theories were true or false. But he did say the following which makes sense to me:

“…I do not equate conspiracy theory with false, crazy, irrational, or delusional. It simply means, when I use, that it has yet to be adopted by the appropriate bodies. The lab leak cover up theory could be true. Should that theory be adopted by appropriate bodies with appropriate open evidence, then I would then call it a conspiracy, and not a conspiracy theory.”

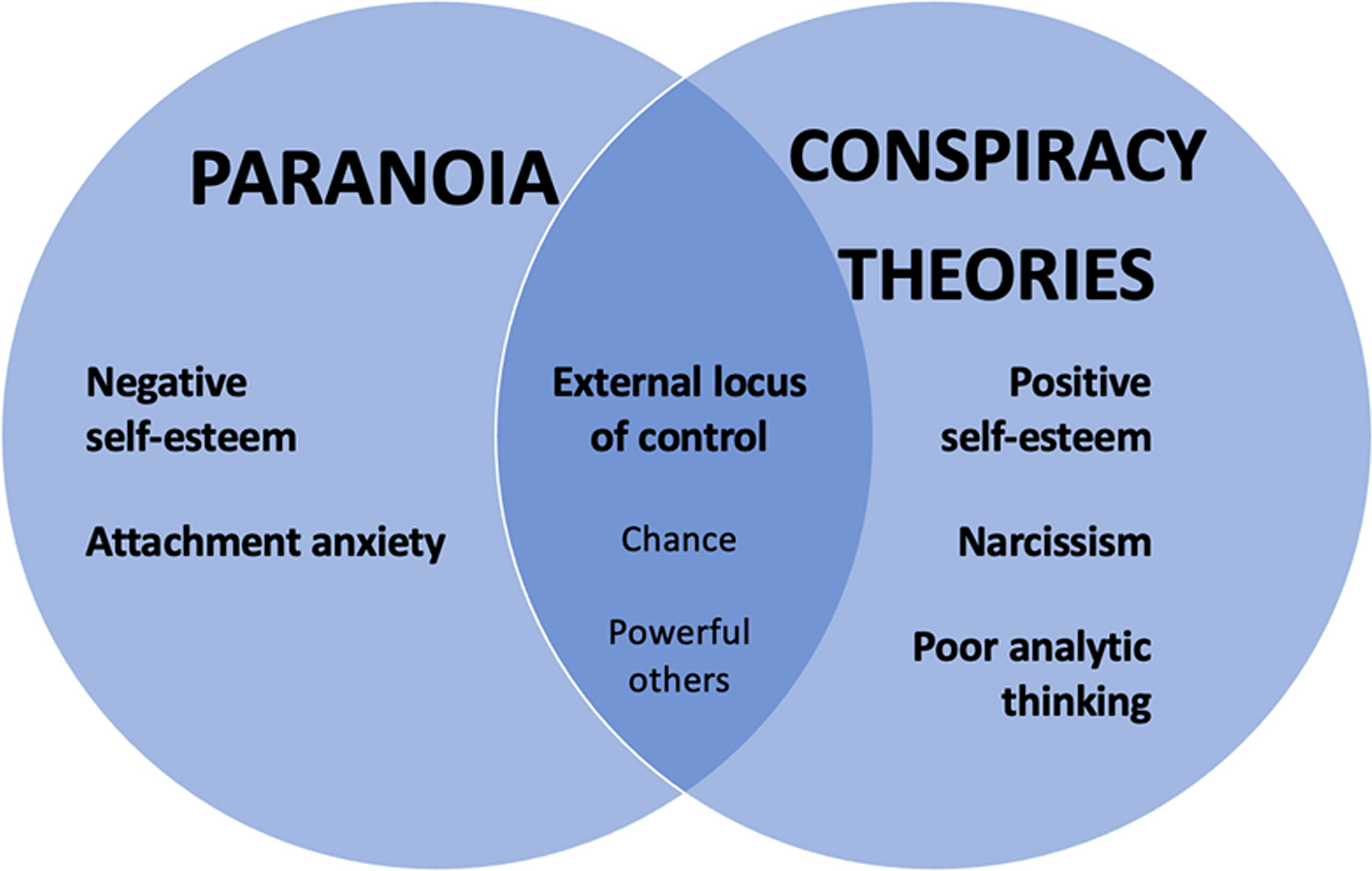

On the other hand, the papers I read by Karen Douglas of Kent were a bit of an eye-opener. For Douglas and her colleagues, “conspiracy theories” were clearly considered aberrations to be explained by psychological analysis, as illustrated in papers such as “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories” and “COVID-19 conspiracy theories.”

I can understand how psychologists might be tempted to look at some conspiracy theories that way, such as the Sandy Hook false flag theory or the Pizzagate theory that Hillary Clinton was running a pedophile ring out of a pizza parlor in Washington, DC.

In the latter case, the gunman who walked into the pizza parlor with an AR-15, Edgar Maddison Welch, has apparently now come to accept that he had it wrong; that is, he no longer believes the theory, realizing there was no evidence for it and he had been misled.

In the case of Sandy Hook, it is obviously outrageous (or should be, unless one believes that particular conspiracy theory) for the parents of the slain children to have to convince anyone that their children were really dead. But in her excellent book about the aftermath of the killings, “Sandy Hook: An American Tragedy and the Battle for Truth,” New York Times reporter Elizabeth Williamson described the campaign of one parent who spent years arguing online with Sandy Hook “truthers,” trying to convince them, with documentation and other evidence, that his child was really dead.

In some cases, as Williamson describes in painful and empathetic detail, he managed to succeed, despite a vicious campaign of lies and smears against him and the other parents by diehard conspiracists. What fascinates me is that this parent had every right to say, “How dare you question that the murder of my son really happened?” Instead, to the extent that he could, he tried to use logic and evidence to fight this particular conspiracy theory.

Is it possible that Sandy Hook was a false flag and that the parents were part of a huge conspiracy to pretend their children had been killed? Yes, it is possible, as absurd as it may sound and as unlikely as it may be. But the history of conspiracies includes a lot of seemingly crazy events (like J. Edgar Hoover approving sending suicide notes to MLK Jr.)

Calling these “conspiracy theories” does not change the facts; only the facts do that.

At this point in my investigations, I discovered something I should have suspected all along: For decades, philosophers have been debating the meaning of the phrase “conspiracy theory” and whether it should be regarded as a pejorative term or not. And this is where it gets really interesting, as often happens when philosophers get involved. (I like to think of them as the cleanup crew for all of our misconceptions; as I have suggested a number of times, I think every science PhD candidate should be required to take courses in the history and philosophy of science.)

It turns out the philosophers are divided into two camps: The Generalists, who think that conspiracy theories are on the whole either highly suspect or usually false; and the Particularists, who insist that each conspiracy theory must be evaluated on its own merits, and that no generalizations can or should be made.

Full disclosure: I find the arguments of the Particularists more persuasive, and so I am going to feature a few of their leading lights in what follows.

A good place to start is with Matthew Dentith, a philosopher based in New Zealand who has worked all over the world, as philosophers have the luxury of doing. In his 2017 paper, “Conspiracy theories on the basis of the evidence,” Dentith argues that so-called “conspiracy theories” should be evaluated in the same way other theories are evaluated, by a careful examination of the evidence.

“…[T]here is no prima facie justification for suspicion of the kinds of evidence conspiracy theorists are alleged to rely upon,” Dentith writes. “Indeed,” he adds, “if we are worried about conspiracy theorists selectively presenting their evidence, then we should also be worried about non-conspiracy theorists doing the same.”

Dentith continued his arguments in a 2018 paper, “The Problem of Conspiracism.” Here he offers a definition for “conspiracy theory” that differs from the dictionary definitions given above:

“Conspiracy theory: any explanation of an event which cites the existence of a conspiracy as a salient cause.”

When defined in this more neutral way, as a number of philosopher have done, the possibility (or even likelihood, in some cases) that a true conspiracy exists in some circumstances is included in the mix. As Dentith puts it,

“The analysis of this broader class of conspiratorial explanations shows that belief in conspiracy theories is explicable—if not outright rational—in a range of cases.”

Another paper I found particularly good for understanding the Particularist view was published in 2021 by David Coady of the University of Tasmania in Australia, entitled “Conspiracy theory as heresy” (It also has the advantage of being short, for busy readers.) To me, Coady is just being reasonable when he comments:

“The bad reputation of conspiracy theories is puzzling. After all, people do conspire.”

And I have to agree, in many cases, when Coady adds, on the next page:

“Although the term ‘conspiracy theory’ lacks any fixed definition, it does serve a fixed function. Its function, like that of the word ‘heresy’ in medieval Europe, is to stigmatise people with beliefs which conflict with officially sanctioned or orthodox beliefs of the time and place in question.”

Finally, for those interested in further reading on this subject, I would also recommend the papers of Kurtis Hagen, an independent scholar formerly at SUNY Plattsburgh. In “Conspiracy Theorists and Monological Belief Systems,” published in 2018, Hagen takes on the psychological view of conspiracy theories as a manifestation of aberrant thinking:

“In alliance with other social scientists, it seems that psychologists have invented a problem so as to posit a psychological explanation for it…[but] rather than focusing on conspiracy theorists, many of these lines of investigation could be turned on people who believe official stories.”

Given my declared biases, I have obviously not done justice to the Generalists in this discussion. But for a good treatment of their counter-arguments I can recommend “Some problems with particularism” by Keith Raymond Harris of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, as well as references in all of these papers. (I was able to access all of the papers discussed here online.)

The argument that so-called conspiracy theories, even the ones that turn out to be wrong, are not necessarily irrational but often have their own logic should not be that shocking. I recall the first time a colleague, for whom I have a lot of respect, told me he thought that the Covid-19 pandemic was the result of a lab accident in Wuhan. I thought to myself, this guy is so sensible about other things, how could he go off the deep end on this particular topic?

Of course, over the past few years I, and many other sensible, scientifically oriented individuals (many with PhDs in highly relevant fields, despite persistent smears on social media) have come to think that the lab origin hypothesis is highly plausible and maybe even the most likely.

So, the bottom line, for me, is that the term “conspiracy theory” is to be distrusted as much as the wildest so-called conspiracy theories, especially when those throwing the term around have a clear motivation for doing so. For some time, I even advocated for getting rid of the term, as one that did no useful work and was actually an impediment to finding the truth in many cases.

I was convinced to change my mind, however, by the muckraking journalist Sarah Kendzior, whose latest book, “They Knew: How a Culture of Conspiracy Keeps America Complacent,” was published last year. As Sarah has argued, there are real conspiracies, way too many of them, so we need conspiracy theories to help explain them. Not all conspiracy theories may be right, and some may turn out to be really crazy in the end, but that is a matter of evidence, not of disdainful hand-waving and dismissal. In that sense, then, the term conspiracy theory is not, and should not be, regarded as pejorative.

I will close with some of Sarah’s thoughts on the matter:

“A conspiracy theory is not the same thing as a conspiracy. Conspiracies are portrayed as elaborate and rare, but they are common and often simple in their basic goals, if not the execution. A conspiracy is an agreement of powerful actors to secretly carry out a plan that protects their own interests, often to the detriment of the public good. The mafia is a conspiracy, the drug trade is a conspiracy, white-collar crime is a conspiracy. War and espionage operations rely on conspiracy. The American Revolution was a conspiracy. Conspiracy is baked into the founding of our nation.

“Conspiracies depend on obfuscation and insularity. Conspiracy theories, on the other hand, are morally neutral and easily accessible. They can be weaponized as propaganda by conspirators, or they can be sincere expressions of the search for truth. Conspiracy theories are group projects open to all: they are perversely democratizing in a country that has lost transparency and trust.”

This is a good one, too.

https://www.start.umd.edu/publication/political-paranoia-versus-political-realism-distinguishing-between-bogus-conspiracy

It's also worth noting that (aspects of) the October Surprise "conspiracy theory" were recently proven true in a confession printed in the NYT.

The lab leak hypothesis doesn't require a conspiracy. Fauci misrepresented the risks versus benefits of gain-of-function research, kept funding it and did not keep oversight of what was happening in Wuhan. When a leak actually happens, everybody acts out of self interest.