Biden approves cluster bombs for Ukraine: A moral failure on multiple counts.

The Convention on Cluster Munitions has been signed by 123 nations. The U.S., Ukraine, and Russia are not among them. Giving them to Ukraine endangers civilians, which is inherently a war crime.

According to numerous press accounts, the Biden administration has approved the shipment of “cluster munitions” to Ukraine from stocks maintained by the U.S. military. This is wrong on so many levels that’s hard to know where to start. But I will.

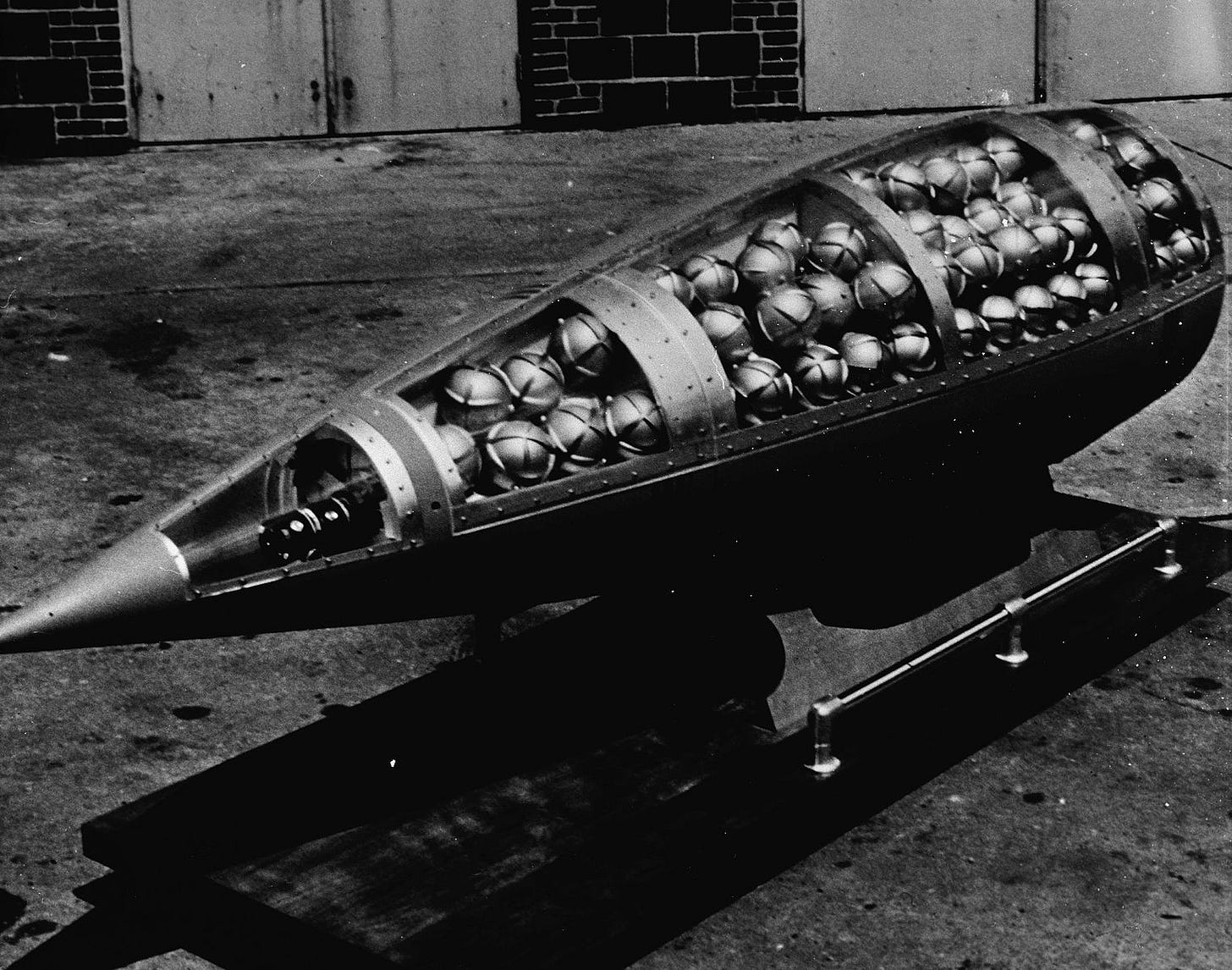

First of all, even calling these weapons—which endanger civilians not only at times of war but sometimes for decades after they have been dropped—”cluster munitions” is one of those euphemisms often employed when someone is trying to sidestep moral issues. They are bombs, as I rightly call them in the headline of this piece. The only difference is that instead of packing one big explosion, their casings can hold 2000 or more “bomblets” which spread out over a fairly large area. For a very good history and description of these weapons, I suggest the Wikipedia entry, which appears to be very good and very detailed.

Before we even get to the moral issues, as the Washington Post article I link to above reports, the sending of cluster bombs to Ukraine is illegal. That’s because Congress has mandated that cluster bombs with a fail rate of more than 1% (the so-called “dud rate”) cannot be produced, used, or transferred to other countries. But the Pentagon has said that its latest testing shows failure rates of up to 2.35%. There are no exceptions to the law, but the Post tells us that Biden administration is getting around it by invoking “a rarely used provision of the Foreign Assistance Act,” which allows the president to circumvent the law if he thinks it is vital for U.S. national security.

The U.S. may also justify its actions because it is not a signatory to the Convention on Cluster Munitions of 2008, along with Ukraine, Russia, and some other countries—even though currently 123 other nations have signed the Convention.

But just because the U.S. has not signed the Convention does not provide the Biden administration with any moral authority to take this action, despite possible legalistic arguments. That’s because international law requires that all nations take every precaution to avoid civilian casualties. The evidence that the use of cluster bombs violates international law in just that way is voluminous.

A number of examples are given in the Wikipedia article. Among them: During the Vietnam War, the U.S. dropped 260 million cluster bomblets on Laos during 1964-1973. Since 2009 alone, 7000 people have been killed or wounded by unexploded bomblets in one Laotian province alone (Ref. 14)

Other examples involve use of cluster bombs by Israel in Lebanon, Morocco in Western Sahara, the Soviets during their Afghan war, the British during the Falklands War, the U.S. in its invasion of Grenada, the U.S. and others during the wars in former Yugoslavia, the U.S. and NATO in Afghanistan, the U.S. and the U.K. in Iraq, Russia in Ukraine, etc. etc.

In addition to outright deaths, civilians are continually being maimed by current bombings and munitions left by conflicts years earlier (similar to the well-known problem with land mines; see the photo at the top.) Handicap International has recorded more than 13,000 cluster bomb casualties, of which 98% are civilians and 27% are children (Ref 90 in the Wikipedia article.)

To make matters worse, Human Rights Watch has reported that Ukraine is already using cluster bombs in its war with Russia.

The deployment of cluster bombs compounds the moral failures of Ukraine’s allies.

Earlier this year, I published a post on this newsletter entitled “Putin is engaging in nuclear blackmail over Ukraine. Do we secretly appreciate it?” In that piece, I tried to argue that fear of nuclear war has already led us to compromise with our moral imperatives to defend Ukraine against the aggression and partial occupation of its territory by Russia. Of course, there is no better example of situational ethics than arguing that avoiding nuclear war invokes the greater good: preventing a nuclear World War III that could kill many millions or even render the planet more inhabitable than it already is. I think the argument can be made, and an argument can be made that it too is a moral argument, as I argue in the piece. But we have to be honest with ourselves: In terms of any kind of absolute morality, it is a compromise of conflicting principles. As I wrote about the failure of the U.S. and other members of the “international community” to get rid of nuclear weapons:

“The message I take away from this is that many of us, deep down, are not really all that keen to get rid of nuclear weapons. And, in response to those who want to do more to help Ukraine, many of us also have the correct and prudent response on the tips of our tongues: We can’t get much more involved because that risks a nuclear war.”

I also wrote, at more length:

“I think most readers are familiar with the famous “Trolley Problem.” It has several versions; all of them, in this thought experiment, pose the ethical dilemma of whether it is okay to sacrifice one or a small number of people to save a larger number (usually by throwing a switch that will re-route a runaway trolley onto a smaller number of people on the track, or, in a more grotesque and body-shaming version, to throw a fat man over a bridge to stop the trolley.)

I would argue that we are currently engaging in a trolley problem solution by not intervening more directly in Ukraine, as Western nations did when they went to war against Nazi Germany or imperial Japan. (Unlike many fellow leftists, I do not blame the U.S. and NATO for Russia’s brutal attack on Ukraine, but that is a discussion for another time.)

In fact I would argue that we are morally compelled to do much more to stop the war, by confronting Russia militarily and halting the killing.”

I think that the last paragraph of what I wrote represents a moral position. I would argue further that the decision to send cluster bombs to Ukraine, which already appears to be using them according to Human Rights Watch, is mainly due to the failure of Ukraine’s allies to do more than they have to stop the Russian invasion. So instead of helping directly, the U.S. is giving Ukraine the weapons it needs to engage in the kind of dirty war that a beleaguered nation receiving less than full support from its allies needs to resort to.

And we may not have much choice than to invoke a higher kind of morality soon, for example if Russia began using troops from Belarus to attack Ukraine. Personally, I do not think that kind of thing can be allowed. But I’m sure there would be all kinds of arguments put forward as to why Ukraine should have to fight on yet another front.

I don’t take these moral dilemmas lightly, of course. They are tough choices, a lot is at stake, and honest people can and do disagree. But we don’t have to compound the moral compromises by engaging in behavior that is clearly and arguably immoral—such as sending cluster bombs to Ukraine.