History of Place: The year a socialist almost became governor of California.

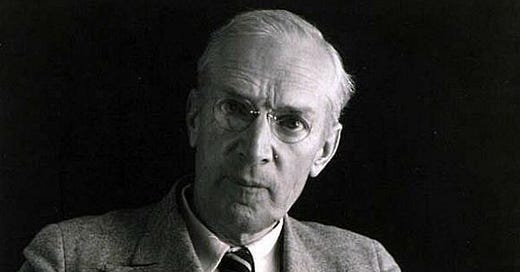

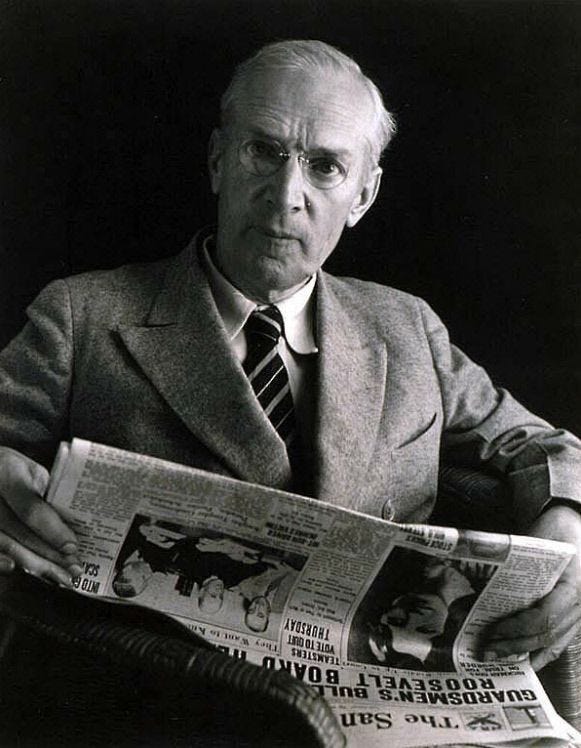

Muckraker Upton Sinclair's campaign changed the political face of the state.

THE Great Depression had hit hard in California. By the early 1930s, 700,000 people were out of work in the state, almost half of them in Los Angeles County. Hundreds of thousands were on relief. Bread lines formed in the larger cities, while in the fields produced rotted for lack of buyers in the East. Families that had lost their homes slept in tents out in the open. Young men rode the rails up and down the state, searching for work.

Those lucky enough to have jobs were going on strike by the thousands, fighting--in what must have seemed to their employers a tasteless show of ingratitude--for union recognition and higher wages. Fruit pickers, furniture workers, meat packers, garment workers, and backlot crews at the movie studios joined the exodus. In May 1934, sailors and longshoremen brought the entire Pacific Coast maritime industry to a halt, leading to a general strike in San Francisco. It was a time of unprecedented social strife in the state and the nation.

On a summer night in 1933, a small group of Los Angeles Democrats met at the California Hotel in Santa Monica. Joining them was Upton Sinclair, who had been invited by Gilbert Stevenson, a Democratic Party activist who had owned Santa Monica's ritzy Miramar Hotel until the Depression had given it to the bankers. As the group discussed the future of their party, Sinclair became increasingly uncomfortable at the realization that he figured heavily in their plans.

While Franklin Roosevelt's election to the United States presidency had given Democrats firm control of the White House, the party was in disarray in the midst of the convulsions shaking California. Republicans out-registered Democrats in the state 2-to-1, and it had been 40 years since a Democrat had occupied the governor's mansion. Moreover, the relief programs of the New Deal had yet to have an effect on California's rising rolls of unemployed and homeless.

Sinclair listened reluctantly as Stevenson and the others prevailed upon him to register as a Democrat and run for governor of California the following year. Although best known for his books--the most famous among them, "The Jungle," was a searing expose of conditions in the Chicago stockyards and had led to the first pure food laws--politics, at least politics of a sort, was nothing new to Sinclair. Twice before, in 1926 and 1930, he had run for governor on the Socialist Party ticket. Yet at first he resisted the group's entreaties, telling them he'd promised his wife he'd quit politics and stick to writing. As the meeting wore on, however, he promised to think it over, and agreed to draft a program for them.

A week or two later, Sinclair declared his candidacy for governor. Shortly afterward, he published his campaign manifesto, "I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty." Subtitle "A True Story of the Future," this slim volume outlined Sinclair's view that the unemployed should be put back to work in the idle factories and fields using credits supplied by the state. Production would be for "use" rather than for "profit," and an elaborate barter system would be set up to distribute goods to the populace. Sinclair called for state support for those unable to work, and for payment of $50 per month for widows, the aged, and the physically disabled. The whole scheme would be financed through drastic changes in the state's tax structure: A state income tax would be introduced, inheritance taxes would would be greatly increased, and unused land would be taxed at a steep rate.

Sinclair's program to "end poverty in California" was soon dubbed the "EPIC" movement, and socialists and non-socialists alike rallied to the cause in droves.

Kay Burton, then a young social worker, recalls how she and her circle of friends were swept into the EPIC movement. "A lot of us who thought we had no future as young people were caught up in that campaign," she said. "We wanted a future and we wanted to help bring about the change that was necessary. Those of us in the Sinclair movement who believed in socialism believed that this was something we could accomplish now. You didn't have to wait for a social revolution to make a fundamental change."

Jim Burford, who became a key EPIC campaign staffer in the Los Angeles area, got involved after going to hear Sinclair speak at a local church.

"We were sitting in the first row of the balcony, and this kind of dried-up, nasal little man comes out on the stage," Burford said. "Yet he had an electric quality to him. He said, here we have fields with rotting tomatoes and rotting potatoes, and here are people without food, why don't we put them together? It made sense to me."

While Upton Sinclair seemed a beacon of hope to many victims of the Depression, the incumbent governor, Frank Merriam, was hardly an inspiration to his Republican supporters. Merriam, who had been elected lieutenant governor in 1930, had fallen into the top job when Governor James "Sunny Jim" Rolph had died in office in 1933. He was a bland, unimaginative politician, and "Hold your nose and vote for Merriam" would later become the unofficial campaign slogan.

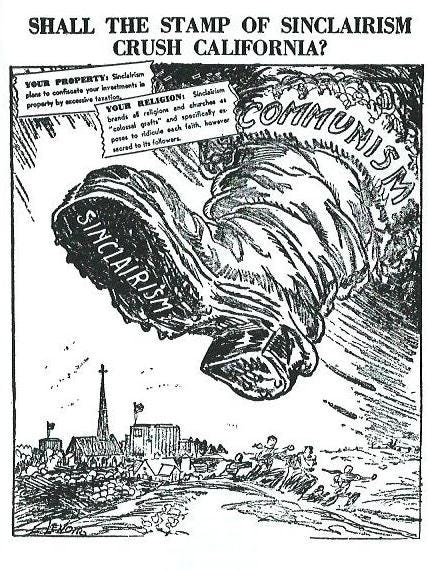

Sinclair swept the field to take an easy victory in the August 1934 Democratic primary, and the threat of an avowed socialist in the governor's mansion sent chills through California's business elite. Meeting at the California Club in Los Angeles, a group of business leaders--led by Harry Chandler, owner of the Los Angeles Times, and including Chamber of Commerce president Byron Hanna, Asa Call of the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company, and Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher lawyer Sam Haskins--devised a strategy to ensure Merriam's victory by attacking Sinclair at every opportunity.

In an editorial titled "Stand Up and Be Counted," the Times declared war on Sinclair:

"Underneath the sheep's clothing of pleasing euphemisms is the same red wolf of radicalism and destructive doctrines that Sinclair has preached for 30 years, and which, given the opportunity, he has scores of times pledged himself in writing to carry out."

The Times, joined by such leading newspapers as the Oakland Tribune and the San Francisco Chronicle, was soon given the opportunity to do Sinclair some real damage. During a trip to Washington, Sinclair stopped off to meet with Federal Emergency Relief Administration chief Henry L. Hopkin and other officials. According to an Associated Press account of the meeting, "Sinclair said he expected an influx of unemployed in the event of his election, and it was concerning that condition that he wished to talk to Hopkins. He said the Federal Relief Administration would be asked to help support these people until they could be taken care of by his program."

When Sinclair returned to California, he held an open house for reporters at his Pasadena home. The discussion ranged over a wide variety of topics. As Sinclair recalled it later:

"They asked me every question they could think of about the EPIC plan, and I answered freely and humanly. One said: 'Suppose your plan goes into effect, won't it cause a great many unemployed to come to California from other states?' I answered with a laugh. 'I told Mr. Hopkins that if I am elected, half the unemployed of the U.S. will come to California, and he will have to make plans to take care of them.'"

The newspapers had a field day with Sinclair's joking remark. "HEAVY RUSH OF IDLE SEEN BY SINCLAIR" and "TRANSIENT FLOOD EXPECTED" cried the next day's headlines. A few weeks later, one of the L.A. papers printed a photograph allegedly depicting "bums" boarding freight trains bound for California in anticipation of a Sinclair victory. But a New York Times correspondent later identified the photo as a still from the Warner Bros. picture "Wild Boys of the Road." The film's juvenile star, Frankie Darrow, was clearly visible sitting on top of a boxcar.

Despite the fakery and exaggeration, the EPIC movement was hard put to counter the media campaign against its candidate. Shut out of the mainstream press, the Sinclair forces had to rely primarily on their own publication, the EPIC News, and on radio broadcasts. The EPIC News was the backbone of the campaign, reaching a circulation of almost 1 million at one point. It was distributed by grassroots campaign workers who were organized in 800 "EPIC Clubs" spread over the state. Many of the clubs had their own special editions, into which they folded advertising circulars paid for by sympathetic local merchants.

"The campaign was like an army that lived off the land," said Jim Burford. "At one time Sinclair was appearing on six to eight statement broadcasts per day. There were appeals for money, and the money came in through thousands of letters a day. People sent in the gold out of bridgework that they didn't use anymore, they sent dimes and quarters. These broadcasts generated enough money to finance themselves. It was like a religious crusade and Sinclair was the guru."

Among the most vociferous opponents of Sinclair's candidacy were the barons of the young movie industry. The studio bosses were still smarting from the raking over they'd gotten in a book called "Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox," which exposed Hollywood's financial wheeling and dealing. Moreover, Sinclair had suggested a series of reforms viewed as anathema by the studios, including nationalization or federal regulation of film-making.

The studios, particularly MGM and Fox, now enthusiastically pitched in to help defeat Sinclair. They enlisted the aid of Kyle Palmer, a Los Angeles Times political writer, who took a leave of absence to help the movie industry organize its part of the campaign. (Palmer later became the Times political editor and a kingmaker in his own right, helping to send a young Richard Nixon to Congress in 1946.)

A series of anti-Sinclair newsreels were produced and shown in theaters during the weeks before the November election. Taking a tip from the newspaper campaign, some of the short films depicted the familiar hobos boarding trains for California. Others featured interviews with respectable looking Merriam supporters, while Sinclair boosters were shown as shabbily dressed, unshaven, and uneducated.

Not everyone in Hollywood rode the Merriam bandwagon, however, especially after the studio bosses tried to pressure screen artists into contributing to Merriam's campaign. According to a number of accounts, studio workers earning more than $100 a week were docked one day's pay for the Merriam campaign. Screenwriter Alan Rivkin, who wrote "The Farmer's Daughter" and numerous other films, was under contract at MGM at the time.

"We were asked in small meetings, and then later individually, to contribute money to the Merriam campaign," Rivkin recalled. "After the meetings, we got together privately and decided not to give any money. We faced the possibility of having our contracts cancelled, but that didn't happen."

If anything, the producers' support for Merriam induced many Hollywood artists to go in the opposite direction. The fledgling Screen Writers Guild passed a resolution charging that studio canvassing for funds amounted to "coercion and intimidation," and a number of writers, including Morrie Ryskind, Gene Fowler, and Dorothy Parker, formed the California Authors' League for Sinclair. While today the political activism of celebrities is somewhat taken for granted, the Sinclair campaign was the first experience in activism for many in that creative community.

Hollywood in the mid-1930s found itself in a strange political contradiction. While major film producers like Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner were businessmen with conservative political outlooks, they presided over the production of numerous socially conscious films during the Depression. Films like Warner's "I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang" were great commercial successes and proved to the producers that a film could have a message and still make money. With the advent of talking pictures in the late 1920s, writers from New York, Chicago, and other cities made their way to Hollywood to prepare the scripts that let the actors talk. The new screenwriters brought a political and social point of view that challenged the provincialism of Hollywood.

One screenwriter active in the Sinclair campaign was John Bright, a young Chicago newspaper reporter who had come to Hollywood in 1929 when Warner Bros. bought his book about the Chicago underworld and turned it into "Public Enemy," starring Jimmy Cagney. Bright went on to share screen credit for several other Cagney gangster pictures before moving to Paramount, where he worked on Mae West's "She Done Him Wrong."

Bright was later blacklisted for his left-wing political activities when the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) swept through Hollywood in that late 1940s and early 1950s, but he recalled that in the early years producers tolerated the growing activism in Hollywood.

"I was a successful screenwriter, and Warner Bros. wasn't too concerned with my extracurricular activity. They were only concerned about my influence on Cagney, in whom they had a narrow vested interest. I had involved Jimmy in the Mooney case (a frame-up of a union leader for a bombing in San Francisco) and when he spoke at a mass meeting on behalf of Mooney, Warner raised hell."

Although Sinclair lost the election, involvement in his campaign convinced some Hollywood artists that they could have a significant influence on political affairs.

On the eve of World War II, Hollywood was caught up in a whirlwind of social and political causes, and few could have guessed that in 10 short years the cold winds of McCarthyism would sweep through the town.

"THE Governor made a last speech over radio, saying that he had caused a careful investigation to be made throughout the State of California, and that the only poor person he had been able to find was a religious hermit who lived in a cave. Therefore he considered his job done, and he proposed to go home and write a novel."

Thus did Upton Sinclair prophesy about his final days as governor in "The True Story of the Future." But November 1934 came and went, and Sinclair was defeated. The final tally:

Merriam, 1,188, 020 votes; Sinclair, 879,537; and Haight, the Progressive Party candidate, 302,519. EPIC supporters were quick to point out that if Haight's votes had gone to their candidate, Sinclair would have won.

Looking back, however, some of those active in the campaign questioned whether Sinclair would have become governor under any circumstances. Kay Burton asked, "How many votes would have been counted for Sinclair even if Haight hadn't been in the campaign? We had no way of being sure that the ballots were being properly counted. The system then was far from what it is today. There was no telling who was really controlling the ballots. There was no telling who was really controlling the polling places. How many watchers could we have at the polls?"

Ruben Borough, who ran the EPIC News during the campaign, told a UCLA oral history interviewer that "Sinclair knew that he didn't have any business in the world trying to administer the state; it was something that was utterly alien to him. He had a naive idea. He had a friend... to whom he was going to turn over the whole state administration. Maybe he would have made him an office manager, but he was going to do the work."

Sinclair himself related, in his autobiography, the mood at his home on election night. Sinclair and his wife Craig sat listening to the returns with a small group of friends, when "very soon it became evident that I had been defeated, and Craig, usually a most reserved person in company, sank down on the floor, weeping and exclaiming, "Thank God, thank God!"

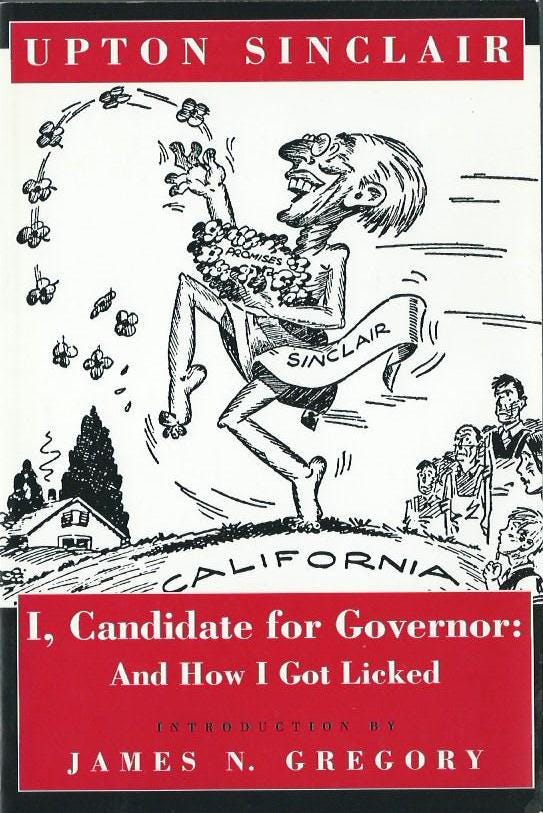

As soon as the election was over, Sinclair retired to write his memoir of the campaign, "I, Candidate for Governor, and How I Got Licked." His abrupt departure left the campaign staff confused and disconsolate.

"Sinclair went into seclusion, Jim Burford recalled. "Nobody could reach him after he lost. Here was the campaign staff, here was a movement that had been built around this single personality, and Moses suddenly went back up on the mountain and crawled into a cave."

Sinclair had gone. In the years before his death he wrote several dozen more books, but he would run for office no more. Yet he left behind a permanent mark on California politics. By the end of the election registered Democrats slightly outnumbered Republicans, and by 1938 the Democratic Party had an overwhelming majority.

While Sinclair lost, many other EPIC-supported won in later campaigns. Culbert Olsen, elected to the state senate on the EPIC slate, went on to defeat Merriam for governor in the next election. Sheridan Downey, EPIC's losing candidate for lieutenant governor, soon found his way to the United States Senate. Jerry Voorhis, who lost his race for state assembly in 1934, made it to the House of Representatives in 1938, where he stayed until he was unseated by a youthful Richard Nixon eight years later. And Augustus Hawkins, who in 1934 became the first African-American ever elected to the California Assembly, went on to represent the 29th District in the House of Representatives.

Looking back on the EPIC campaign, it is tempting to dismiss this ill-fated movement as the delirium of a hopeless Utopian. Yet in the midst of a devastating depression, the nearly 1 million Californians who voted for the EPIC slate must have found a voice in Sinclair's plea from the powerless to the powerful:

"Is it altogether a Utopian dream, that once in history a ruling class might be willing to make the great surrender, and permit social change to come about without hatred, turmoil, and waste of human life?"

Note: The above article is adapted from a piece I wrote for the July 15, 1984 issue of the Los Angeles Daily News Magazine, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Sinclair's run for California governor. It could happen again!

As readers of “Words for the Wise” will have noticed, the newsletter so far is a mix of “old” pieces updated for the present day and new, original material which I hope everyone will find topical and interesting. As time goes on, the mix will shift to more of the new and less of the old; but I hope subscribers will understand my desire to save some of my earlier work from oblivion by finding new readers for it.

Please read on for more about the Sinclair piece, and a dedication to a wonderful friend I lost not long ago.

Dedication and afterword.

In 1984, after three years working at the ACLU of Southern California on a lawsuit against the Los Angeles Police Department for spying on peaceful political groups, the case was settled with generous terms for our plaintiffs and a huge award of attorney's fees to the ACLU. My work was done, but the ACLU generously bestowed me with six months of severance pay as compensation for the 80 hours/week I (and the attorneys) had worked on the case. With that grub stake, my career as a freelance journalist was launched.

I began writing for the L. A. Weekly, thanks to my friend and colleague Marc Cooper, who was news editor there at the time; and also for the Los Angeles Daily News. My editor there was the wonderful Linda Perney, who had moved to L.A. after a long career in New York to edit the paper's Sunday magazine. Linda took me under her wing, and I must have written at least a half dozen features for her in the mid-1980s. Sadly, some time after moving back to New York, Linda died, in 2010. We kept in touch from time to time, and if I recall right, she died of cancer.

Also instrumental in my early journalism career, and in the perspectives I brought to the Upton Sinclair piece, were my supervisors at the UCLA Oral History Program, where I worked part-time from the early 1980s until I moved to Paris in 1988. Ron Grele, who later became director of Columbia University's oral history program, and Dale Treleven, who took over from Ron, where my oral history mentors. I have used those skills in many articles I have written since the early days of my writing career, and continue to do so today.

As is evident from the Sinclair piece, I interviewed a number of people who had been involved in the EPIC campaign. The most memorable interview was with John Bright, once a star screenwriter who had fallen on hard times when I caught up with him in a dingy, smoky L.A. apartment, where he was living alone and largely forgotten. But from my research I knew he had been a brave and legendary political activist in earlier days, despite the pressures of the McCarthy era. That interview was one of the first glimpses I had of the adventure that journalism could be, and continues to be, all these decades later.