Is Russell Brand "innocent until proven guilty"? In a court of law, yes; in the court of public opinion, probably not. Sometimes that's how justice must be done.

In a courtroom, presumption of innocence is critical for a fair trial. But outside the courtroom, in cases of rape or sexual assault, it implies the accusers are lying until proven otherwise.

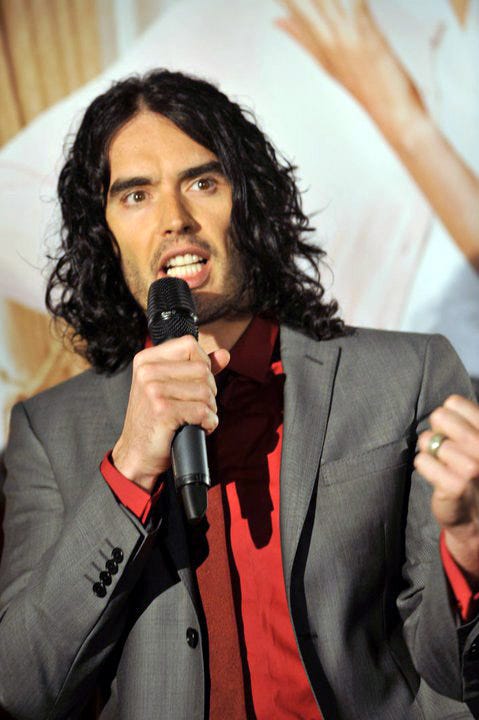

By now I assume the wise readers of “Words for the Wise” will be aware that comedian and actor Russell Brand has been accused by four women of rape, sexual assault, and related abuses. The allegations were reported after an investigation by The Sunday Times, Times of London, and Channel 4 Dispatches. These publications tend to be behind paywalls, but the details have been repeated by a number of other outlets, including The Guardian, The Independent, and the New York Post. The New York Times also reported the allegations, leading in both headline and first paragraph with Brand’s denials (more on that journalistic approach in a moment.)

Some of the most graphic details of Brand’s alleged abuses come from a woman identified as “Alice,” who is now about 30 but told reporters that Brand had abused her and groomed her when she was 16 years old. While that was technically within the legal age of consent, these details, if true, suggest a very exploitative relationship.

Brand has his supporters, of course. They notably include Elon Musk, who reportedly exposed himself to a woman on a private flight and paid her compensation; Andrew Tate, awaiting trial in Romania for rape and human trafficking; and Alex Jones, who among many other things recently lost a defamation suit filed by parents of Sandy Hook children killed by a shooter a decade ago (Jones had accused the parents of faking the deaths of their children.) Oh, and Tucker Carlson, whose credentials for truth-telling need no elaboration here.

Brand also has a significant number of supporters, almost all men, on social media, whose unsurprising refrain is that he is “innocent until proven guilty.” This presumption of innocence defense is often trotted out in such cases, especially when the accused abuser is someone famous and otherwise admired for other things they have done in life.

But there are at least two main problems with this defense.

First, the presumption of innocence is a legal concept that applies to court cases, usually criminal in nature, after the accused has been formerly charged and is undergoing trial. Juries are rightly instructed that prosecutors must prove their cases beyond a reasonable doubt. It is not a concept that must bind us outside that narrow context, and indeed it seldom does in real life.

Second, when “innocent until proven guilty” is invoked outside this context (or even wihin it to a more limited extent) it implies, heavily, that the accusers are lying. This is an unavoidable contradiction in the concept, and an unavoidable consequence of it. For that reason, as citizens, we sometimes draw conclusions based on evidence produced outside of the courtroom, often revealed in journalistic investigations just like the ones that Brand has been subject to in this case.

Brand has not (yet) been criminally charged, but London’s Metropolitan police have solicited complaints from the public, his agent and publisher have cut ties with him, and he is likely to suffer other consequences and reputational damage as time goes on. (For example, his ex-wife Katy Perry, along with Dannii Minogue, have been cited by reporters as sources for his past alleged bad behavior.)

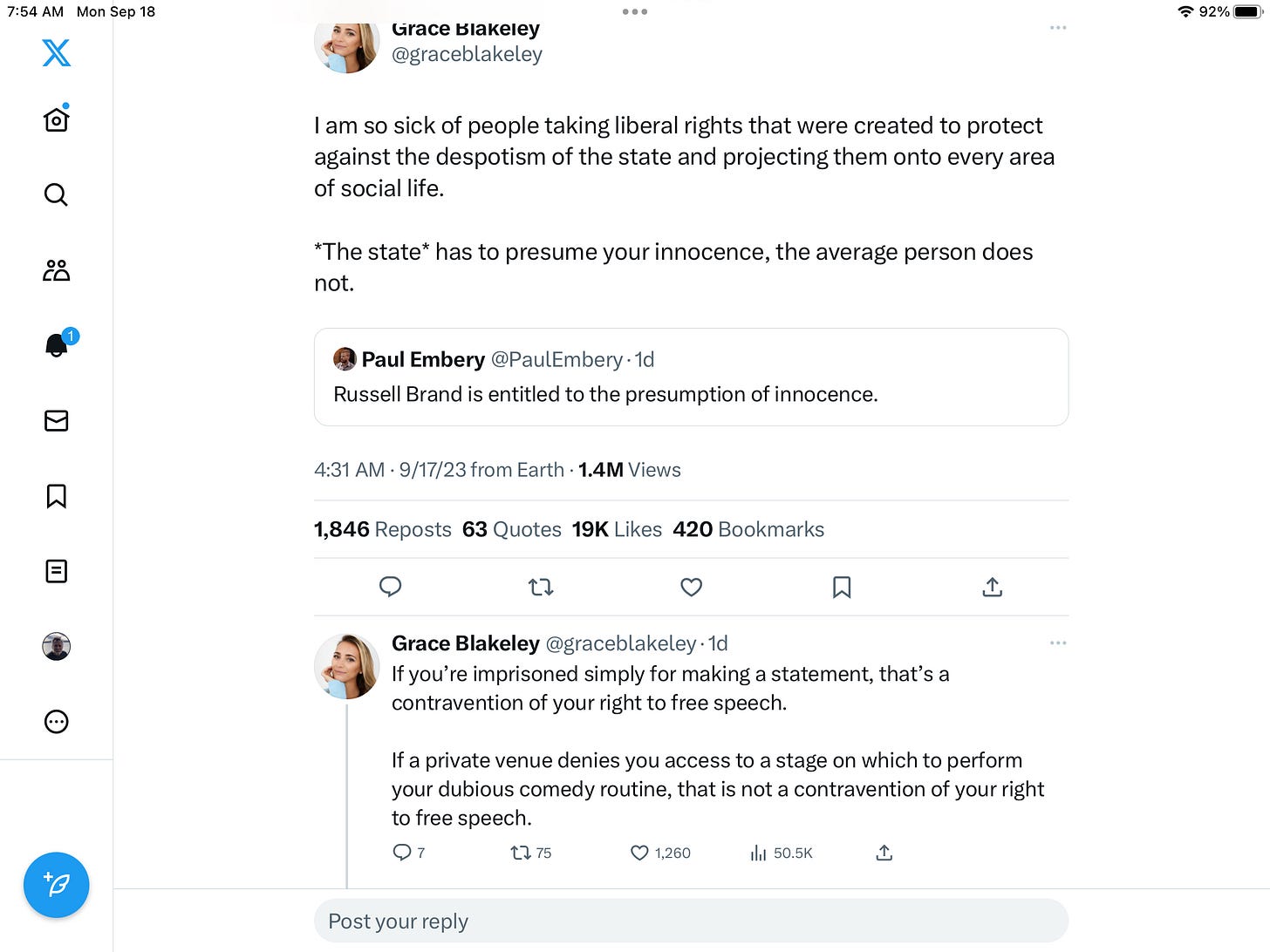

A passionate statement of the misuse of the presumption of innocence concept was expressed today by journalist and commentator Grace Blakesley on Twitter:

Also, regarding the framing of the New York Times story cited above, feminist writer Jessica Valenti penned a Twitter thread that also criticized the privileging of Brand’s denials over the claims of the alleged survivors:

Of course it’s possible that all four women who spoke to reporters about Brand are lying, misremembering, or otherwise getting it wrong. It’s also possible that the dozens of actresses and other victims of Harvey Weinstein’s abuses got it wrong when they told their stories to reporters at the New York Times and The New Yorker. But given how many there were, and the existence of corroborating witnesses, most of us (I would say all honest people) believed the survivors long before Weinstein stepped into a courtroom and was found guilty by multiple juries.

Likewise, many people believed Christine Blasey Ford’s accusations against Brett Kavanaugh even though they were long ago and there was minimal corroboration. (Liberals and Democrats did not believe Tara Reade’s accusations against Joe Biden, however, although she had more contemporaneous corroboration than Ford, but that’s a matter for another post.)

I’ve been a #MeToo reporter myself for the past eight years, and have investigated the claims of dozens of survivors of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and bullying (the victims and the abusers have been both men and women.) Not one of these cases, all of which had academic settings, has ended up in a criminal court, although there have been quite a few Title IX proceedings and other institutional investigations. A number of accused perpetrators have been fired or forced to resign as a result of these journalistic investigations, which—one might argue, and I certainly would—are a form of trial in which evidence is evaluated and presented to the public and to officials. And in nearly every case, that I or other reporters have investigated, the survivors have approached journalists because all other avenues to justice (or even acknowledgement of their stories) had failed.

Russell Brand may never be charged or face a jury, although it’s certainly possible that he will. In the meantime, insisting that he must be considered innocent until proven guilty is not only an insult to the alleged victims, but a negation of them and their stories. Listen to what they have to say, follow the new allegations that are likely to arise now that the first brave survivors have spoken out, take their stories seriously even if you want to ask for more evidence before deciding—but do not declare Russell Brand “innocent” based on a formalistic phrase that has little meaning in real life.

The courtroom is not necessarily the only venue where justice is done. We all know, or should know, about the tiny percentage of rape cases that actually make it to trial. There are many ways to seek out the truth and achieve justice. When survivors of abuse talk to the media, it’s usually because they can find no other way.

Comment removed that was highly offensive to women and especially insensitive to survivors of abuse.

I'm on the fence about how the media are allowed to expose high profile people regarding accusations before they have been charged legally. I'm in no doubt there is some truth in what is said but the publicity alone will be highly damaging.

Of course if he is found guilty he should face the consequences but i do wonder how many other stars have used their status to exploit people but somehow escaped public judgement. Rock stars and groupies for example.