It's déjà vu all over again on Covid origins. This time, the much-maligned raccoon dog takes the rap. Was it framed?

Last week the media was ablaze about "new data" that allegedly pointed to raccoon dogs for sale in a Wuhan market as the source of the pandemic virus. But there's a lot they forgot to tell us.

(Note: This is an expanded version of a short piece I published today on Truthdig.)

Last week it looked like the long and bitter debate over Covid origins might be a wrap. The headlines came fast and furious.

First The Altantic and reporter Katherine Wu, which had the “scoop,” on March 16: “The Strongest Evidence Yet That an Animal Started the Pandemic.”

Close on its heels, that same evening, the New York Times and Science, with “New Data Links Pandemic’s Origins to Raccoon Dogs at Wuhan Market” and “Unearthed genetic sequences from China market may point to animal origin of COVID-19,” respectively.

Within 24 hours, headlines around the world echoed the same theme. The pandemic had begun, they declared, with one or more infected animals in the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, China. Raccoon dogs—canines closely related to foxes, but not to raccoons despite the resemblance-- were the “guilty” parties.

But there was a problem. The so-called “international team” of scientists pointing the finger at the raccoon dog had not published a paper. They had not even posted a so-called “preprint” online, a pre-publication manuscript that allows the scientific community to comment and makes suggestions on a study as it begins the arduous peer review process at a scientific journal.

To make matters worse, many of these major media outlets—with a couple of exceptions—told their readers that the group making the claims was made up entirely of vocal, well-known advocates for a so-called “zoonotic spillover” hypothesis for Covid’s origins, as opposed to the controversial “lab leak” hypothesis favored by some other scientists. One slight exception was the Washington Post, in a March 17 article by reporters Joel Achenbach and Mark Johnson, which pointed out that one member of the group “has long favored the market theory.” In reality, that was true of nearly everyone else the paper quoted, without telling readers that.

A Science story by Jon Cohen also identified the “allegiances” of members of the team.

This failure to identify the clear allegiances of the scientists being interviewed was journalistic malpractice, and a gross violation of journalistic ethics. Do you think I’m exaggerating? Imagine, if you will, that CNN had on an “expert” in warfare and geopolitics to talk about Russia’s war against Ukraine. The expert explains in detail why he thinks Russia’s aggression against its neighbor is justified. Only later do we find out that the “expert” was actually an active duty Russian general.

Is there any question that failure to properly identify the Russian general would have deprived CNN’s viewers of critical information they needed to judge the validity and objectivity of his views? Of course not. And yet the reporters who quoted well-known zoonosis proponents such as Michael Worobey, Kristian Andersen, Eddie Holmes, Angela Rasmussen and others involved in the “international team” knew full well, from their previous coverage of the Covid origins controversy as well as the voluminous social media production of these researchers, that they were fierce partisans.

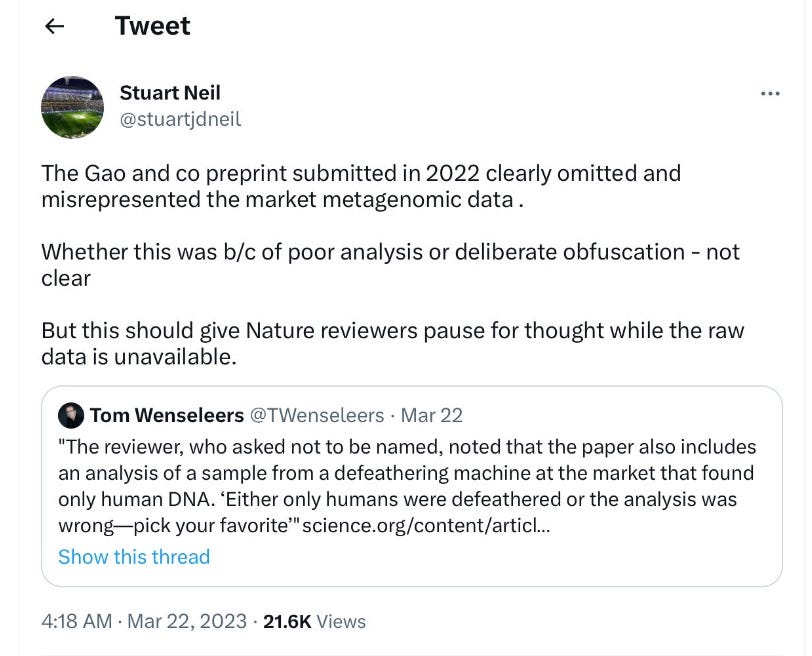

Helped by a compliant international media corps, the “international team” was coasting along to yet another public relations triumph for the zoonosis hypothesis. But then things got complicated and a bit nasty: It turned out that the data upon which the scientists were basing their raccoon dog conclusions actually came from a Chinese team, led by former Chinese CDC director George Gao, which had been trying to get its own paper published for a year (it is reportedly under revision for the journal Nature.)

The Gao team had recently deposited so-called “metagenomic” data in the GISAID database, a repository for coronavirus sequences, as a condition of its paper being published. The international team, either tipped off or through sharp-eyed diligence, had spotted the data and run with it.

Why would they do this, rather than wait for Gao et al. to publish?

Gao’s team had concluded that the pandemic did not begin in the Huanan market, but that the market was the site of a human to human “super-spreader” event, similar to what might happen at a rock concert. Other researchers have suggested the virus might have been transmitted in toilets and mahjong rooms at the market.

This apparent attempt by another group of researchers to pre-empt the Gao paper made some folks mad, although in different ways. The World Health Organization immediately blasted China for withholding data that held clues to the pandemic’s origins, and which it only learned about when the Gao team deposited it as part of the requirements for publication (most journals require researchers to post such genomic data in a publicly available database upon publication.)

And GISAID blasted the international team for using the Gao et al. data to “scoop” the Chinese team before it had a chance to publish, in violation of the database’s terms of use.

This week, the international team finally posted a 22-page report on its interpretations of the Chinese data on a preprint server. As a number of scientists have pointed out, the report does not prove that raccoon dogs transmitted the pandemic virus to humans in the Huanan markets. At most, it confirms what we already knew, that raccoon dogs were sold in the market, along with many other wild animals, in the period leading up to the pandemic.

Among the most important commentaries on the matter came from Jesse Bloom, a highly respected virologist at the Fred Hutchison Cancer Center in Seattle. Bloom has remained assiduously neutral on the Covid origins question from the beginning, and when he does speak out it is always in measured, strictly scientific terms. Indeed, Bloom waited until there was an actual manuscript to review before issuing a Twitter thread giving his views. Pointing out that the data was still not available, he offered what he called a “partially informed assessment.”

Bloom started off with a description of the original Gao et al. preprint, which appeared to contradict the conclusions of two papers published in Science last July—on which a number of members of the international team were coauthors—that the pandemic had started with two zoonotic spillovers in the Huanan Seafood Market. (A new paper challenging the multiple spillover conclusion has just been published, one of several studies that take issue with the Worobey/Pekar findings.)

Bloom cites at least two caveats about the Gao et al. study. One is that no raw data from sequencing of the samples was available; and two, since it is well established that human infections with SARS-CoV-2 began in Wuhan “no later than Nov 2019,” Bloom writes, that “limits how much can be concluded from either positive or negative samples collected on Jan 1.” (That is obviously a problem with the Worobey/Pekar findings as well, which are based on cases reported well into December 2019 and thus cannot represent the origins of the pandemic.)

Bloom also points out, as have others, that samples taken from the market and positive for the virus were not associated with any particular kind of market vendor: There were “similar positivity rates” for stalls selling wildlife, seafood, and vegetables.

The new study, which had the benefit of analyzing the underlying data, found samples possibly indicative of animals that had been sold in the market before January 2020, including the mitochondrial DNA from a raccoon dog. One sample in particular included both traces of SARS-CoV-2 and raccoon dog DNA, a lot of it. But, as the team itself acknowledges in its new preprint, in Bloom’s words, “the fact that [mitochondrial] DNA is found in a sample doesn’t mean that species was infected with SARS2. It just means material from that animal ended up in the same place as viral RNA, which was widespread in the Huanan Market by Jan 2020.”

A number of other scientists have also made this point, leading some to call the new study a “nothingburger.” Bloom doesn’t go quite that far, pointing out that the new analysis does tell us something about what animals were being sold, and—if the zoonosis hypothesis is going to be pursued—”knowing more about animals could help trace supply chain, which is a valuable line of investigation.”

Nevertheless, Bloom concludes, we will not learn much more about Covid origins unless we have information about cases prior to December 2019—which China has steadfastly refused to provide to WHO or anyone else.

And, unfortunately, there is little evidence that Chinese scientists have continued to pursue leads to what a purported “intermediate host”—whether a raccoon dog or other animal—might be. That’s probably because China’s official position is that the pandemic started outside China, possibly in a U.S. bioweapons facility or frozen food that had been imported into China.

In many ways George Gao and his colleagues are in a tough spot, no doubt engaged in delicate negotiations both with Chinese officials about what data they can release publicly, and with the editors and peer reviewers of Nature about how much data they must release to get their paper published. It’s bad enough that publication of the Gao paper has been delayed more than a year now; it’s even worse when a team of partisan scientists inserts itself into the process and interferes with it, as GISAID has charged.

(The international team has denied the accusations it violated the GISAID terms of use, and the database has rescinded a ban on the group accessing the data despite continuing controversy over what really happened.)

Bottom line here: Despite all the initial media hype (the New York Times and some other publications have already issued updates considerably more modest in their claims), the new study, now that we can read it and see what it really says, does not move us closer to knowing how this killer pandemic began. Perhaps the Gao et al. paper, if and when it is finally published, will help.

Meanwhile, the lesson is clear: Believe the science, not the headlines.

"strong evidence" raccoon dog story also appeared in Belgium:

https://www.demorgen.be/tech-wetenschap/genetisch-bewijs-gevonden-wasbeerhond-gaf-mensheid-coronavirus~b5e1d74bc/

and the Netherlands:

https://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/genetisch-bewijs-wasbeerhond-gaf-mensheid-coronavirus~b5e1d74bc/

(same text by same authors)

Very nice summary! So good to read some non-lemming journalism on SARS2 origins.

I wrote this substack going into a few more details in case you are interested:

https://vbruttel.substack.com/p/the-strongest-evidence-yet-that-major