Jeffrey Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, Julie K. Brown, Felicia Sonmez, and how the media has mucked up #MeToo coverage.

Survivors tell their stories, journalists win prizes. Are we setting the bar too high for victims of abuse to make themselves heard?

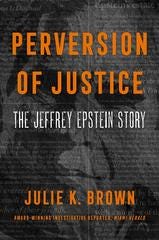

Until I read Julie K. Brown’s book about Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes, “Perversion of Justice,” I thought that “She Said” by New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey was the best I had read about how journalism is actually done—at least the kind of sensitively-sourced reporting required to write about victims of sexual abuse and tell their stories.

Now I think it’s a close call, even though they are two very different books. When Kantor and Twohey did their investigation of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse of actresses and others who worked for him, they had the mighty weight of the Times and its seemingly limitless resources behind them, plus the Times’ prestige. We never heard about Kantor and Twohey struggling to pay their rent or make ends meet, and they ended up sharing a Pulitzer for the book.

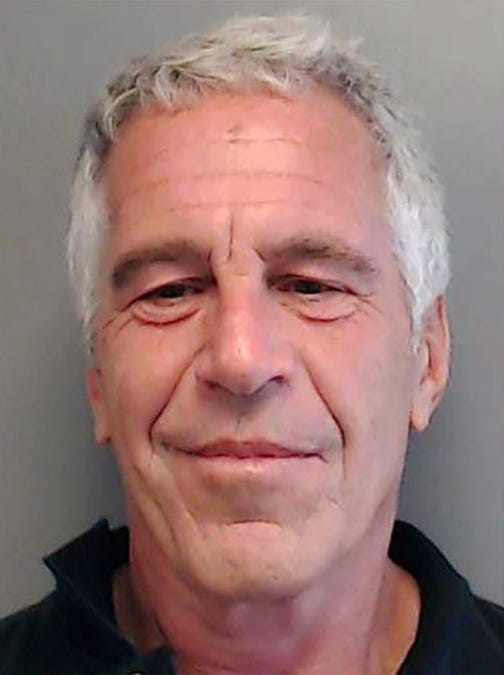

With Brown, we get that story, and a lot more besides, about what it is like to be a struggling reporter working for a struggling newspaper like the Miami Herald. Every time Brown’s editors let her get on a plane or pay for a hotel room, she was happily surprised. Fortunately, Brown did get the support she needed to do the stories that helped land Epstein in jail, even if he managed to escape justice in a way that still raises considerable suspicion (Chapter 39 of Brown’s book is entitled, “Jeffrey Epstein Didn’t Kill Himself.”)

While it’s clear from reading “She Said” that Kantor and Twohey were very empathetic with the victims of abuse they were trying to get on the record, and finally did in many cases, Brown had something else going for her: As a working class girl and single mother, she could identify closely with the once struggling teenagers whom Epstein and his accomplice Ghislaine Maxwell brutally exploited, and they with her.

Nevertheless, the two books do have something important in common: They tell the story of female reporters trying to get survivors to speak about their horrific experiences on the record, to satisfy the demands of their mostly male editors that the victims must be named—otherwise there is no story.

I will have more to say about my own experiences doing this kind of reporting lower down. But the main issue I want to raise here is, who is benefitting from this insistence that survivors must risk everything for their stories to be told? True, in some cases—Epstein, Weinstein, Cosby (at least for a while), et al.—abusers do get their just punishments, and the survivors get some kind of justice, but at what cost to the victims?

Successful abusers have power, expensive lawyers, and sometimes even prosecutors in their pockets.

I assume most readers have kept up with the Weinstein, Epstein, and Cosby cases, among others. The daily news coverage of those stories hit the basics of what happened. But one reason I recommend reading these books—including Ronan Farrow’s “Catch and Kill,” about the Weinstein case, which also won a Pulitzer— is that the devil is always in the details. There is no way to appreciate the great lengths that the abusers and their enablers—which in Epstein’s case included a bevy of state and federal prosecutors, including former Labor Secretary Alex Acosta—went to in their efforts to protect these powerful men from the consequences of their actions.

Of course, the enablers will never admit that is what they did, but this conclusion is inescapable once you read the details that Brown and the other reporters lay out. The Jeffrey Epstein case was especially egregious, and Brown provides so much evidence of the collusion of prosecutors with Epstein’s lawyers that she leaves little doubt. I am not naive, at least I hope not, but it really was a shock to this reporter of 43+ years’ experience to read about Epstein’s attorneys basically being given a veto by prosecutors on what he was going to be charged with and what not.

As might be expected, this was mostly the doing of men, although Brown’s story does feature some heroes in law enforcement, men who tried to nail Epstein and were thwarted at every turn. There are also a few female heroes, but the pressure on them was even greater to let Epstein off with what turned out to be a sweetheart deal. It is almost certain that Epstein continued to abuse teenage girls while supposedly serving his sentence in Florida.

Brown is also uncompromising about the famous men who either enabled Epstein or quite possibly benefitted from his trafficking of underage girls: Harvard linguist Steven Pinker, who helped Epstein’s defense with “linguistic” advice, and went on to be part of Epstein’s genius club at Harvard; Bill Clinton, who, Brown shows, flew on Epstein’s private jet more times than he has been willing to admit; Prince Andrew, who, if Virginia Roberts Giuffre is to be believed, had sex with Giuffre at Epstein and Maxwell’s invitation; and attorney Alan Dershowitz, who vigorously and viciously defended Epstein, and whom Giuffre insists did the same. (And there are others, of course, whose names may be waiting to be revealed.)

Let me pose a question to readers: Whom do you believe, Alan Dershowitz or Virginia Roberts Giuffre? Who has the most reason to lie? I have my own answer ready, if anyone is interested.

The occupational hazards of being a #MeToo reporter, and the occupational hazards of being a #MeToo reporter’s source. Are survivors the bait in the clickbait?

On July 21, Washington Post reporter Felicia Sonmez sued her own employer, along with several of its editors including recently departed top editor Marty Baron, in the D.C. Superior Court. I suspect that Sonmez will write a book about her experiences one day, but in the meantime I strongly—strongly—recommend reading the 63 page Complaint in the case, which is shocking reading in many ways.

Sonmez contends that the Post and its editors violated her rights under the D.C. Human Rights Act, by subjecting her to “unlawful discrimination and a hostile work environment based on her gender, and her protected status as a victim of a sexual offense and retaliating against her for engaging in protected activity by protesting Defendants’ unlawful practices.” Sonmez is also asserting a claim for “negligent infliction of emotional distress.”

Sonmez relates in her Complaint that she was sexually assaulted in September 2017 in Beijing by Jonathan Kaiman, then the Beijing bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times. Sonmez was also not the only victim, and Kaiman was forced to resign his position the following year. In her Complaint, Sonmez provides a detailed timeline of how the Post treated her as a result of this experience, especially whenever she said something public about it or about other #MeToo cases. In essence, she was told that she could not be “objective” about sexual misconduct and was twice banned from doing any coverage that touched on it in any way.

As one Post editor, Cameron Barr, allegedly told Sonmez, by speaking out publicly she had “taken a side on the issue” of sexual assault. This rather amazing position was repeated, in effect, by most of her other editors, nearly all of whom were men. I don’t want to patronize my readers, but can one imagine that a Black reporter would be told they could not cover the George Floyd case, an Asian-American reporter told they could not cover China objectively, or a woman told she could not cover AOC’s re-election campaign? (I’m sure readers could think of even better examples.)

But Sonmez, a sexual assault victim, was told repeatedly that she could not cover #MeToo issues, as if there are really two “sides” and a reporter is biased if they think that sexual assault is wrong. (Imagine also a crime reporter getting kicked off their beat because they say out loud that they think murder is wrong.)

But one of the most remarkable aspects of Sonmez’s story is that her editors were constantly changing their minds about what she could and could not cover, instituting a ban and then lifting it not once but twice. In other words, these guardians and gatekeepers of journalism, at one of the nation’s most important and prestigious newspapers, really did not have a fucking clue what they were doing and what the rules should be.

The Post and its editors have 60 days from the filing of the Complaint to file their Answer, that is, their defense to the allegations. It will be very interesting to see what they have to say.

My own career as a #MeToo reporter began six years ago, when I was a correspondent at Science magazine, for which I had then worked for a quarter of a century. My first investigation involved Brian Richmond, curator of human origins at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who was accused of sexually assaulting a colleague and sexually harassing students. After the museum performed its own inquiry (actually the third it carried out, as the first two swept the matter under the rug) Richmond was forced to resign. I well recall a conversation with Science’s news editor, in which he told me that it was journalistically okay to be against sexual assault.

I have followed that principle ever since, and become what might be called an “advocacy” or “movement” journalist on the #MeToo beat. Over the years, I have conducted dozens of investigations, for Science, The Verge, and most recently on my own blog. Like all advocacy journalists (a proud tradition in the U.S. and other countries) I make sure I have the facts right, but I don’t pretend I don’t have an opinion on where those facts lead.

But Science and I did have a parting of the ways after it published the Richmond story. There is a long back story to why that happened, but for me the triggering event was when my editors put pressure on me to in turn put pressure on a victim of sexual assault to name herself in my story, despite a carefully worked out agreement I had with her that she would not have to do so. The editors backed off when I refused to even approach her about it—it would have been a serious breach of trust—but it was the final break in a long-simmering breakdown of mutual trust, as the news editor himself put it publicly (and correctly.)

After a similar experience later on, in which editors (and lawyers) again wanted me to urge (read pressure) survivors of abuse to go on the record despite their fears that they would be retaliated against, I decided to go independent with my #MeToo reporting (I explained this decision at length in a piece a couple of years ago for the Columbia Journalism Review.)

In the old days of reporting on sexual assault and rape, reporters and victims were not put under this kind of pressure. It was understood that victims did not have to be named for their stories to be told, and often they were not—it was left to them to make the choice.

But we are in a different era now. As their books reveal, Brown, Kantor, Twohey, and Farrow spent a huge amount of time trying to talk victims into going on the record. Why? In many or most cases, it was because the publication’s lawyers and editors insisted on it. Despite my differences with Science’s editors, they allowed me to publish the Brian Richmond story without that condition; but that was probably the last time. The journal, in step with most other publications, now requires its reporters to get at least some victims on the record before they will publish their stories; and, very important, they insist on documentation, the results of an institutional investigation, before they will go to press.

In other words, the words and stories of the survivors are not enough, nor are the assurances of reporters that they are talking to real people whose accounts they have attempted to verify in various ways, using standard journalistic methods.

Over the past 13 months, I fought a defamation lawsuit brought by an academic I had written about. The case was settled in a way I found favorable to the best interests of freedom of the press and the survivors (for details, please read the numerous entries on Balter’s Blog.) But the pressure was enormous.

Fear of legal action and other kinds of retaliation—for example, damage to their careers—is constantly on the minds of survivors who want to tell their stories, but fear the consequences. Journalists and their editors need to be careful that, by urging victims to go on the record (and thus mollifying the lawyers as well as the business side’s desire to generate as much traffic as possible), they are not adding to the trauma and exploitation that the victims have already suffered.

Survivors usually do not have lawyers or the money to pay them. They should not have to worry that they might need to keep their stories hidden away if they don’t please those with the power to help tell them.

There is some research indicating that people, who acquire power, wealth, and/or influence, sometimes fall victim to self-affirmation fallacies that reduce their empathy with others, especially subordinate or relatively powerless others. This is explored int he work of Paul Piff and others. It may be that this is not just a class problem, justifying exploitation of the poor, but also an issue among men and women, even in places like academics and other places of employment. With exploring, perhaps.