Pandemic Politics: How Much Does it Matter if the Lab Leak Hypothesis is Right or Wrong?

The debate turns more on politics than on science; we may never know; and it shouldn't change what we do in the future. As for fighting racism, that's a given.

“A phrase much used in political circles in this country is ‘playing into the hands of.’ It is a sort of charm or incantation to silence uncomfortable truths. When you are told that by saying this, that, or the other you are ‘playing into the hands of’ some sinister enemy, you know that it is your duty to shut up immediately.” — George Orwell, June 1944

So, even before I began writing this commentary, I had a dilemma and a conflict of interest. Last week, a U.S. senator publicly attacked a friend and colleague of mine, and of course my natural instinct was to jump to her defense. The senator was Ted Cruz of Texas, a Trump lackey, one of the most dishonest men in American politics, and, pardon the profanity, a disgusting racist fuck.

The friend and colleague was Apoorva Mandavilli, a former colleague of mine at the New York University science, health, and environmental journalism program. Apoorva is an award-winning, stellar science journalist; founding executive director of Spectrum, a leading source for accurate coverage of autism; and currently a reporter for the New York Times, where her reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic has brought her well-deserved respect and praise.

Apoorva is also a passionate anti-racist, uncompromising in her opposition to bigotry of all kinds. Ted Cruz, on the other hand, like his friend Donald Trump, is uncompromising in his exploitation of racism, including the anti-China, anti-Asian racism that allowed Trump and other Republicans to deflect responsibility for the hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 deaths that their negligence directly caused.

So it pains me greatly to say that Apoorva’s righteous anti-racism led her to make a very big mistake: She expressed a major bias in a legitimate debate over the origins of the virus that has caused this deadly pandemic. In a May 26 Tweet, now deleted, Apoorva said:

“Someday we will stop talking about the lab leak theory and maybe even admit its racist roots. But alas, that day is not yet here.”

Apoorva’s mistake wasn’t that she was too anti-racist, although Cruz’s opportunistic remark seemed to suggest he thinks so when he referred to her “tender feelings” (as a woman of color, no less.) The mistake, of course, is that we don’t judge the veracity of a scientific hypothesis by the politics of those who support or oppose it, much as we are sometimes tempted to.

Later, Apoorva deleted the Tweet, explaining:

This Tweet seems to suggest that her colleagues, but not her, will be covering the pandemic origins story going forward. If so, that would be the right journalistic call by the Times, because Apoorva’s original Tweet demonstrated a bias that unfortunately goes far beyond what is acceptable in journalism today, even as reporters are called upon to abandon false “objectivity,” both-sides coverage, and pretending that blatant lies are just opinions—a lesson we have learned, at least I hope, during the four nightmare years of the Trump administration and its assault on truth, science, and reality itself.

So what was my dilemma and my potential conflict of interest as a journalist? For days, I debated with myself about how I was going to deal with Apoorva’s Tweets and their significant fallout: Would I discuss them at all, even though they were a good example of what I plan to discuss in this commentary? Would I bury this lede in the middle of this piece, so that Apoorva and our mutual friends and colleagues would not be mad at me for seemingly making an example of her? Would I use this example but not name her and just say “a New York Times reporter” or some such?

In other words, would I engage in prior restraint and self-censorship and avoid potential peer pressure to withhold what I really thought, to avoid embarrassing a friend and colleague? Would I risk colleagues thinking that I was an advocate of the lab escape hypothesis for COVID-19 origins, or worse, a “conspiracy theorist” for entertaining that as a possibility?

(I think it likely that Apoorva is already sufficiently embarrassed about this episode. CNN’s Oliver Darcy reported that her colleagues at the Times were none too happy about her Tweet, especially since they were actively investigating—or re-investigating—the lab leak hypothesis.)

Obviously I decided not to let those considerations stop me from commenting on the Tweet and the fallout from it. But I struggled with the question, which is part of the problem I will be exploring below. Clearly, Trump et al. have exploited the apparent origins of the virus in China for racist purposes, and fostered an atmosphere where Asian-Americans (and Asians around the world) are killed and violently attacked. What should be a purely scientific question—where did the virus come from and how did it infect humans—has become a big political question, because both sides of the debate think they have a political dog in the fight.

I will claim one advantage in the discussion: I don’t have an opinion about whether the lab escape hypothesis, the natural transmission (animal to human) hypothesis, or some other alternative (bioweapons research, etc.) is correct. But I do think that the clear efforts of many scientists and science journalists to avoid “playing into the hands” of Trump and the reactionary right, to quote George Orwell from above, not only biased their views and the media coverage, but has made it easier for the right to claim some kind of victory—as many of the same scientists and science journalists now have to explain why some were too quick to dismiss the lab escape hypothesis in the first place.

For my thoughts on all this, please read on.

One person’s “conspiracy theory” is another’s gospel

A couple of days ago, the “conservative” New York Times columnist Ross Douthat published a column entitled, “Why the Lab Leak Theory Matters.” If you are a liberal or a progressive (like me) your first reaction might be to decide that if Douthat thinks it matters, then it probably doesn’t. We will get to that soon. But my real point is that if everything gets politicized, which is probably unavoidable, then Job One for journalists and other thinking citizens is to figure out how to separate the wheat from the chaff when an important issue—such as how a pandemic that has killed millions got started—is under debate.

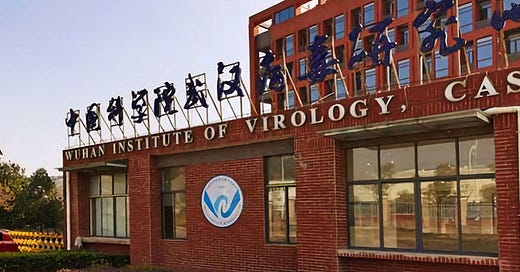

But whether through “liberal bias” or just not wanting the Trump racists to win the argument, too many journalists failed to do that, from the very beginning of the pandemic. From the start, reporters began referring to suggestions that the virus emanated from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which had been studying bat coronaviruses for years, as “conspiracy theories.” At first, the term was restricted to claims that the released virus was manufactured in a Chinese bioweapons program, and either escaped accidentally or was deliberately released. But before long, “conspiracy theory” also came to include an accidental release of a virus that was being researched and perhaps had been genetically engineered to study its properties, such as its virulence and transmissibility.

Last week, in an excellent analysis, New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait examined some of these early mistakes, and I highly recommend reading his piece (“How Twitter Cultivated the Media’s Lab-Leak Fiasco.”) As Chait pointed out (it’s worth quoting at length):

“Not everybody who dismissed the lab-leak hypothesis as a debunked crank obsession was this indifferent to the facts of the case. Far from it. The problem is that the people with the strongest views had the weakest interest in the truth. An asymmetry of passion between their insistence that the lab-leak hypothesis was false and racist and the weaker feeling of others—who, at most, believed the hypothesis was only possibly true—created a stampede toward the most extreme denial.”

Chait also briefly discussed the role that Senator Tom Cotton played in fanning the flames of prejudice against China and the Chinese, when he endorsed the lab-leak theory:

“Some progressive journalists insisted that since the lab-leak theory was favored by some people who also endorsed different conspiracy theories, it was itself inherently tainted by racism… To other progressives, the fact that Tom Cotton had endorsed the lab-leak theory inherently proved its falsity…”

But my favorite quote from Chait’s article, which I will discuss myself towards the end of this piece, slices through what the stakes are and are not in this debate:

“I don’t know if this hypothesis will ever be proven: I don’t care, and I’ve never cared. There’s no important policy question riding on the answer riding on the answer, nor would confirming the thesis in any way vindicate former president Trump’s horrific mismanagement of the pandemic.”

I also recommend a recent piece by Matthew Yglesias, “The media’s lab leak fiasco,” in which Yglesias argues—convincingly, I think—that Cotton did not really claim the virus came from a Chinese biological warfare program. Again, the conflation of that allegation with the lab-leak hypothesis would end up creating a lot of confusion among average citizens and provide fuel to the most extreme and racist charges against the Chinese.

(It also hasn’t helped that recent articles urging that we take another look at the lab-leak hypothesis, by former New York Times science reporters Nick Wade and Donald McNeil, Jr, were penned by two men who have themselves been accused of racism in various contexts. On the other hand, serious scientists with real PhDs are also coming forth to say that we need to seriously investigate and keep an open mind.)

The campaign against blaming the Wuhan Institute of Virology as the main culprit in starting the pandemic got a big boost in February 2020, when a group of public health scientists published a now famous statement in The Lancet pushing back against the lab-leak hypothesis and attacks on China by Trump and other right-wingers. The statement provided unabashed support for China’s scientists:

“We sign this statement in solidarity with all scientists and health professionals in China who continue to save lives and protect global health during the challenge of the COVID-19 outbreak. We are all in this together, with our Chinese counterparts in the forefront, against this new viral threat.

“The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation around its origins. We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin.”

In my view, expressing solidarity with Chinese scientists, and trying to work with them, was laudable and sensible—especially in those early days of the pandemic when international cooperation was critical to figuring out what had happened and how to control the virus. But to label suggestions that COVID-19 might not have a “natural origin,” when scientists knew so little about the virus at the time (and still know so little about its origins), as “conspiracy theories” was an act of scientific malpractice.

Moreover, buried among the author list on this statement was Peter Daszak, president of the New York City-based EcoHealth Alliance, a non-profit organization that has received millions of dollars in U.S. funds for work on viruses in China, including at the Wuhan institute. Daszak, who, emails obtained by the anti-biotech group U.S. Right to Know show, actually organized and wrote the statement while trying to hide his key involvement, has come under fire for conflicts of interest—a subject I will discuss in a future post. But in the early days of the pandemic, especially, he was a key go-to guy for reporters trying to get their bearings on what to think and what not to.

(Yes, USRTK has its critics, but they did not fabricate the emails.)

Nevertheless, the Lancet statement was very influential, and served as a bludgeon against anyone who might, as Orwell puts it above, not know that their duty was to shut up immediately. Today, it is a given that China and its scientists were not fully forthcoming about what they knew about the virus, a problem that brings us straight to where we are today—with the lab-leak hypothesis once again getting close scrutiny, while a shrinking number of reporters and scientists continue to insist that it should not. (Thus disagreeing with President Joe Biden, who has called for making such inquiries a priority over the next 90 days.)

Of course, more in the background, serious research was going on, and that too contributed to skepticism about the lab origins theory. A key paper by Kristian Andersen of the Scripps Research Institute in California and his colleagues, published in Nature Medicine, took a close look at the genome of the virus and concluded that its features were most consistent with a natural origin rather than “a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.” And while some scientists took issue with these conclusions—pointing out, among other things, that the lab escape hypothesis could envision a wide variety of ways SARS-CoV-2 could have ended up at the lab—those scientists and science journalists who wanted some real research to hang their conclusions on greeted the paper with enthusiasm.

Before leaving this section, I think it’s important to point out that President Donald Trump did not start out blaming China for the pandemic. Yglesias, in the piece cited above, quotes a number of statements that Trump made in the early days of the public health crisis:

“Great discipline is taking place in China, as President Xi strongly leads what will be a very successful operation. We are working closely with China to help!” enthused Trump in a February 7, 2020 Tweet.

“I think they’ve handled it professionally and I think they’re extremely capable and I think President Xi is extremely capable and I hope that it’s going to be resolved” he told Fox News.

Of course, all this was before Trump fully realized that he was going to (rightly) take the blame for the pandemic raging out of control in the United States. Only then did China become the enemy, and the anti-Asian racism campaign kick into full gear, as the “Wuhan virus” or “China virus” eroded his presidency (all that Trump cared about, as we would find out.)

How much does it matter?

Before we can answer this question, we need to take a sober look at whether we will ever be able to distinguish between the competing hypotheses. Moreover, there are almost certainly more than two, although the lab-leak vs. natural origins hypotheses have come to stand in for a whole host of possibilities ranging from biological weapons research gone astray or biological weapons research deliberately released (the latter seems the most unlikely, given the relatively low fatality rate of the virus); to a scenario in which Chinese scientists had already isolated SARS-CoV-2 from animals or people and were in the early stages of working with it when it escaped; to the natural origins theory, which in itself can encompass a number of scenarios including or not including the Wuhan market where wild animals were slaughtered and sold.

Indeed, many scientists are troubled by the fact that an “intermediate host” between bats, widely thought to be the natural host of a virus ancestral to SARS-CoV-2, and humans—probably some other wild animal, such as a pangolin—has still not been identified, despite a lot of searching by Chinese scientists. As the months go on without identifying that intermediate host, the lab-leak hypothesis has gained new legs. (Critics of the hypothesis continue to insist that there is no new evidence for the lab-leak scenario and that the current discussion is mostly concocted by the media and right-wingers like Tom Cotton and Ted Cruz; but the truth is, sadly, that there is not much new evidence for the natural origins theory either.)

Moreover, some now acknowledge, the current investigations, by WHO and The Lancet, into COVID-19’s origins continue to be compromised by conflicts of interest, including the involvement of Peter Daszak in both of them. For an excellent review of these issues, I recommend a piece last January in Wired by Roger Pielke, Jr., “If Covid-19 Did Start With a Lab Leak, Would We Ever Know?”

So, does it matter, and should we care, or is Jonathan Chait right in saying that there is no important policy question riding on the answer?

Personally, I think both views are partly right. If we knew that this deadly pandemic was due to a lab escape, perhaps we would have a greater incentive to beef up the containment of high-security labs to avoid future such episodes (this is not the first time there has been such a lab leak, and it probably won’t be the last.) And if the virus springs from natural origins, we might spend more money looking for so-called zoonotic diseases before the pathogens responsible get to jump from animals to humans.

But shouldn’t we be doing all that anyway? It’s not that we have not been warned. Back in 1995, my friend and colleague Laurie Garrett, the science journalist and award-winning author of “The Coming Plague,” told us that we would one day face a pandemic of the kind we are facing now. Moreover, she and others have pointed out, this is very unlikely to be the last one, even in our lifetimes. (Laurie, I must add, was one of the first to see that what was happening in Wuhan in the earliest days of the coming pandemic, while some “experts” much in the media eye today were expressing skepticism.)

If there is something to be gained from a scientific or public health perspective from knowing the details of how this pandemic started, then by all means let’s try to study that question. But while we are doing that, let’s begin preparing for all of the worst-case scenarios, not just the one(s) that fit best into our preconceptions.