Places in history: Where Nazis tried to hide the murderous truth

At the Terezin concentration camp, in former Czechoslovakia, child drawings and writings survived the Holocaust

TEREZIN--It is a custom for visitors wandering the thicket of tombstones in Prague's Old Jewish Cemetery to place small rocks on top of the markers, a practice said to date from when the Jews lived in the desert and there were no flowers to be had.

Sometimes people tuck folded pieces of paper between the rocks, perhaps directed at whatever unseen spirit they think resides there. I picked one up at random. It read: "Peace of mind, peace of heart, for me, for everyone."

Of the 12,000 tombstones in the cemetery, the first was placed in 1439 and the last in 1787. Most of these deaths, though not all, were from natural causes. Yet the somber reverence revealed in the faces of visitors reflects a more contemporary history, in which the death of a European Jew is all too likely to have been a murder.

As if to underscore this point, a former ceremonial house at the entrance to the cemetery has for some years been given over to an exhibition of drawings and writings of children who were imprisoned at Terezin, a town about 37 miles northwest of Prague. During World War II, the Nazis evacuated Terezin's population and turned the town into a concentration camp.

Between November 1941 and May 1945, when Czechoslovakia was liberated by the Soviet Army, more than 80,000 Jews passed through the camp on their way to Auschwitz and similar destinations. An additional 33,000 never made it any farther, dying at Terezin of starvation, disease or torture.

Despite the harsh conditions, the Germans tried to create the illusion that Terezin was a "model" camp. Many artists and intellectuals were imprisoned there, including the writer Karel Polacek and the young composer Viktor Ullmann, and the Nazis tolerated a considerable degree of artistic freedom. The prisoners put on operas, concerts, and plays, including a number of original works.

The Germans used this artistic activity to try to convince a delegation of the International Red Cross in 1944 that the Jews were being well treated. The following month, however, the Nazis discovered that a number of paintings depicting the brutality of life at Terezin had been smuggled out of the camp. Several artists were moved to a nearby prison. One was beaten to death on the spot. Others were sent to Auschwitz.

Few of the works created by the adult artists of Terezin survived. One that did was an opera composed by Ullmann that did not get beyond the rehearsal stage at the camp. Ullmann died in Auschwitz, but the score was discovered many years after the war and was finally performed in Amsterdam and elsewhere.

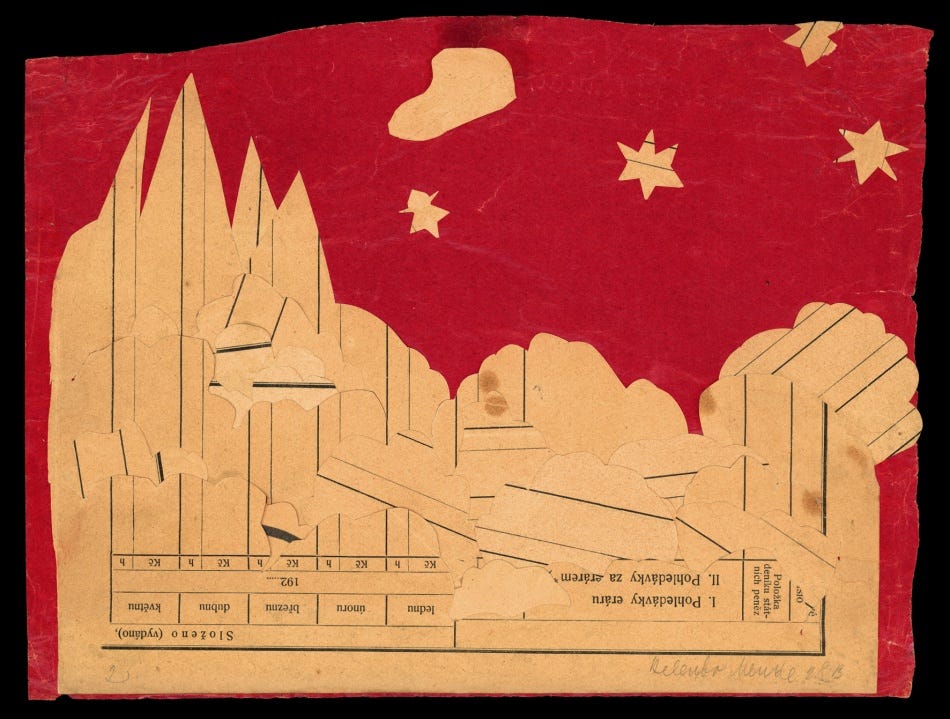

Yet among the camp's inmates were 15,000 children. Most of them were separated from their parents and housed in various buildings in the town. The Nazis forbade formal schooling, but did allow art classes. Some 4,000 drawings have been preserved, as well as poetry and copies of magazines and other publications that the children produced secretly with the help of adults assigned to live with them.

As I walked through the exhibition, it struck me that the drawings fell into two categories. Many depicted monsters and grisly scenes of hangings and disease--scenes drawn from the depths of children's nightmares. Yet others were elaborate fantasies of flowers and butterflies, kings and queens. An explanatory note in English captured the essence of things with the ingenuousness of a clumsy translation:

"Their reminiscences and their dreams, which did not always come true, are alive in their drawings even nowadays."

One section was devoted to the boys who lived in building L417-I. With the help of their adult supervisor, Valtr Eisinger, they secretly published a magazine called Vedem (We Lead.) It appeared weekly until the autumn of 1944, when the entire group was sent to Auschwitz. The editor was a 14 year old boy named Petr Ginz. A photograph of Petr showed an awkward adolescent with a shy, bucktoothed smile, a cowlick of dark hair falling over his forehead.

The following morning I made the hour-plus trip to Terezin, taking the bus from the Fucikova station in Prague. The town was founded at the end of the 18th century on the order of the Emperor Joseph II, who named it Theresienstadt, after his mother, Maria Theresa. At that time Bohemia and Moravia were part of the Habsburg domains, and Theresienstadt was built as a fortress against the Prussians. Two sets of fortifications were constructed: a larger one, which became a free royal town, and a smaller outpost called Little Fortress.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Theresienstadt had fallen into insignificance, but the Little Fortress was converted into a military prison. Its most notorious inmates were the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip, who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo in 1914, and two of his confederates in the plot. By the end of the war they helped to launch, all three had died in Theresienstadt of tuberculosis.

Today, the Little Fortress is the site of a national cemetery and memorial for the victims of Terezin. During the Nazi occupation, the Gestapo used the fortress as a prison for political prisoners. Most of the inmate were Czechs, but in the course of the war, resistance fighters from Slovakia, Poland, France, Italy, Yugoslavia, and other countries were brought there, as well as Jews in the Terezin ghetto who had been accused of petty offenses.

Roaming through the prison blocks, I felt like a voyeur peering into the misery of other people. Yet some things are almost impossible to imagine. A tiny cell, with a single wooden bunk--where did the 12 people who were once imprisoned in it stand, where did they sleep? A long underground tunnel emerged onto a quiet patch of grass. Here, on May 2, 1945--six days before Soviet troops arrived--51 boys and girls, members of a clandestine youth group, were put up against the fortress wall and shot. I ate lunch in a small restaurant near the entrance to the prison, and learned later that this building had been the SS officers' canteen.

A bridge over the river Ohre leads from the Little Fortress to the town of Terezin. Before the war, the population was about 7,000, but by 1942 almost 60,000 Jews were crammed into the ghetto. During the autumn of that year, the camp was hit by epidemics of various diseases and almost 100 people died each day.

But the Terezin that greeted me was a quiet, dusty provincial borough, a place of little laughter and much forgetting. The only reminder I could find was an unobtrusive plaque on a Neo-Classical building just off the main square, the former L-417-I, where Petr Ginz and Valtr Eisinger spent their last months before being sent to die at Auschwitz.

At first the dead of Terezin were buried in a hollow outside the town walls. But in October 1942, at the height of the epidemic, the Nazis forced the prisoners to build a crematorium nearby. From the outside, the building vaguely resembled a church; but inside, in place of pews, were four massive black ovens.

An elaborate system of pulleys operated their heavy doors, which had once received bodies rolled in on long iron trolleys that still sit, rusting, in the building. While I gazed at one of the trolleys, my imagination drifted back to the children's drawings at the museum in Prague, and to one watercolor in particular, by a girl named Helga Pollakova. She would have been about 14 when she came to Terezin. It was a haiku of a painting: Brown twigs, green stems and leaves, a red splotch for the sun, set down in vivid brush strokes against a white background. The composition was strikingly light and airy. I thought that perhaps, while painting it, Helga had briefly floated above the reality that would soon claim her.

The image evaporated, and I was left staring at the cold black iron of the trolleys.

Note: This piece is adapted from two stories about Terezin I published, in November 1990 in the International Herald Tribune and in the Los Angeles Times in April 1991. At that time, soon after the fall of Communism, Terezin was not that well known in the West, but I believe that in the years since much more has been written about it. Some of the details might now be out of date, but probably not much.