Remembering Mike Davis: On the front lines

The famed L.A. historian combined intellectualism with activism in a way we seldom see. I had the fortune to know him in the middle of a struggle that is still raging today.

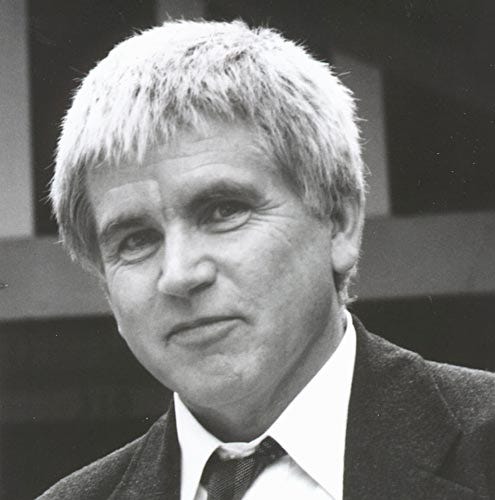

Ever since Mike Davis—the famed activist, L.A. historian, author of “City of Quartz” and many other books, and MacArthur Foundation award winner—died in October, I have been thinking about what I wanted to say about him. Meanwhile, of course, the tributes have gone flying by—perhaps the most an avowed socialist has received since the death of Eugene Debs or Norman Thomas (or, in L.A., Dorothy Healey.) I’ve got a tidy pile of obits here from the mainstream New York Times, the liberal New Yorker, the left-wing Jacobin, and of course the Los Angeles Times, whose very existence over most of its history depended on the minimum number of people reading the kinds of things Mike had to say about Los Angeles history.

Then, just today, news struck that jolted me out of my procrastination and made it clear what I needed to say about Mike. Today, Monday November 14, some 48,000 teaching assistants, postdocs, researchers and others employed by the University of California system walked out on strike. According to union leaders quoted by the Washington Post, it’s the “largest academic strike in higher education in U.S. history…”

So, I first met Mike Davis in 1975, when I was a graduate student and teaching assistant in the biology department at UCLA, and Mike was the same in the history department. What brought us together was a teaching assistant union organizing drive, that culminated in a one day symbolic strike. We got few of our demands, and teaching assistants have been trying to organize at UCLA and other UC campuses ever since, to various degrees of success (and lack thereof.) Compared to what we were able to achieve, the current strike looks like the real thing, a biggie.

Then as now, UCLA was divided into North Campus (humanities, history, languages, etc.) and South Campus (the sciences.) Mike was working on his PhD thesis about the history of Los Angeles, the famous PhD the history department would famously refuse to award him. When he finally published the thesis as “City of Quartz” in 1990, it became a “surprise” best seller, the media wrote (and still writes.) Yes, I suppose it’s true that for a book that tells the truth about any city to become widely read is a “surprise.” But Mike’s book was a sensation, and that made the attacks on it from the right-wing all the more vicious.

In 1975, however, we vaguely knew that Mike was working on a PhD on L.A. history, but I don’t recall that we knew what it was really about. What we did experience, and what I recall so well, is when Mike would show up to meetings of the TAs in the Royce or Haynes Hall auditoriums, leading a phalanx of fellow history grad students, make modest but wise speeches about the hard tasks that faced us, and toss off anecdotes here and there about the labor organizing he had done before he arrived at UCLA. He was the sort of working class philosopher of the kind we so keenly admired in those days.

I have other memories of our organizing efforts, and so do some others I tracked down and consulted about their recollections of that TA organizing drive. I recall a fiery French grad student in the French department, Francesca, who would strut up and down the auditorium aisles making snide but apt remarks against the administration (I also recall my disappointment on learning that she was married, to another militant in the strike effort); I recall the determination of the grad students and their disdain for compromise with the administration, which thought it could just wait us out until we folded; and I recall being the only TA from all of the relatively conservative South Campus who actually participated in the one-day strike we finally pulled off (my fellow science grad students covered for me and taught the parasitology lab I was responsible for.)

In the years after we left UCLA, I saw Mike from time to time, running into him at political events in L.A. (As the chief organizer/paralegal/investigator/spokesperson for the ACLU’s 1980s lawsuit against the Los Angeles Police Department for spying on peaceful political groups, I knew everyone on the left in the city, including a community activist named Karen Bass, who was one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit.)

But it was only years later, when “City of Quartz” was published, that I fully understood what Mike’s legacy would turn out to be. Critics accused the book of being “negative” about Los Angeles, but in reality, it was a very optimistic book. It told us what we needed to know about how the city worked, who really ran it, and what we needed to do to change it. Mike set an example of how being an intellectual and being an activist were not mutually exclusive, and how knowledge could be a weapon in the struggle against racism and injustices of all kinds—which Los Angeles, like so many American cities, would allow to fester until they periodically boiled over in historically violent upheavals.

All these years later, Mike still represents to me the quiet confidence that things really can change if you organize and fight and just keep at it until it makes a difference. Oh, and that a socialist can write a best seller and win a MacArthur Foundation grant even if he never got his PhD. Now that’s the kind of thing that can really set an activist to dreaming.

Mike just missed this new academic strike that, perhaps in some small ways, he and I and so many others helped to bring about by just moving the gears on the giant capitalist machine a little tiny bit, such that decades later they would give way enough to make a difference. Maybe it will take 1000 years before the kind of just society so many of us have dreamed of all our lives comes to be. But I know that Mike died still believing it would happen, one day.

I just wish he were here to see this big monster TA strike. He would have enjoyed it greatly.