Sinéad O'Connor, we hardly knew ye

The Irish singer is gone, but what she stood for lives on--and her music, of course.

When Sinéad O'Connor tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live” in 1992, I had been living in Paris for four years out of the total 30 I would end up spending there. There was no YouTube back then, and I don’t have a clear memory, but it seems that French news stations would probably have shown a clip from the live broadcast—especially since France was, and still is, a quasi-official Catholic Country. I certainly knew about it—how could one not?—and I know that my reaction was very favorable.

That was not because I knew much of anything about the Catholic clergy’s sexual abuse of children in Ireland or anywhere else for that matter. By the late 1980s, reports had begun to surface in the Irish media about clergy abuse, in many cases committed by priests who had been raping children for decades. But Sinéad O'Connor certainly knew about it, and all the other abuses that the Catholic Church in Ireland and elsewhere was guilty of. But it was still a dirty, guilty secret; it would take another nine years before John Paul II acknowledged it at all, and it was not until 2010 that Pope Benedict XVI would apologize to the Irish people.

But to me, O’Connor became an instant hero. First, as a long-time lefty, I was anti-religion and saw the Catholic Church as one of the most oppressive institutions on Earth. (The famous chapter in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, “The Grand Inquisitor,” in which Jesus comes back to Earth and is immediately arrested by the Inquisition, was always one of my favorite works of literature.)

And second, as a life-long rebel, I admired anyone with the courage to flaunt authority and make a statement based on conviction, no matter what the consequences. And that’s what O’Connor did: Tore up a photo of the Pope on live TV, when no one could stop her, no one could edit it out, no one could revoke the act, no one could make us forget it or pretend that it never happened.

I wish I could say that I was a big fan of O’Connor’s music back then. But I wasn’t, really. I thought her version of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” was very pretty, and that she sang it beautifully, but I didn’t buy her albums or go out of my way to listen to her songs. That only came much later.

In more recent years, as O’Connor’s mental health struggles became highly mediatized—often in very gross ways, including disgusting expressions of schadenfreude—I began to pay attention to her again, because I knew she was having a very rough time and I sympathized. I think many of us secretly realized that when her son, Shane, killed himself in January of last year, it was an open question whether O’Connor herself was going to survive the loss. Obviously, she did not. Although the cause of her death is being kept private by her family (including her three remaining children) I think it’s natural to speculate about it. You don’t get over the loss of a child, ever.

I don’t know about you, but often I don’t really discover an artist until they are gone. And I sometimes find myself grieving much more than would be expected in such circumstances, although the reasons can differ. When Leonard Cohen died, I didn’t feel as badly as I thought I might, because I had spent all of my adult life listening to his music, had gone to one of his last live concerts in Paris, and had most of his albums. His memory was safe with me.

But I think there is another reason we grieve for people we have lost. It’s our way of keeping them alive, of holding onto them for as long as possible. There’s nothing original about this insight, of course, but recently there was an uproar when the American Psychiatric Association last year added Prolonged Grief Disorder to its diagnostic manual.

Bullshit. My best friend died in 2004 and I am still grieving for him, I will always grieve for him, and I don’t want to stop grieving for him. If someone wants to call me crazy, fuck them.

Okay so back to Sinéad O'Connor.

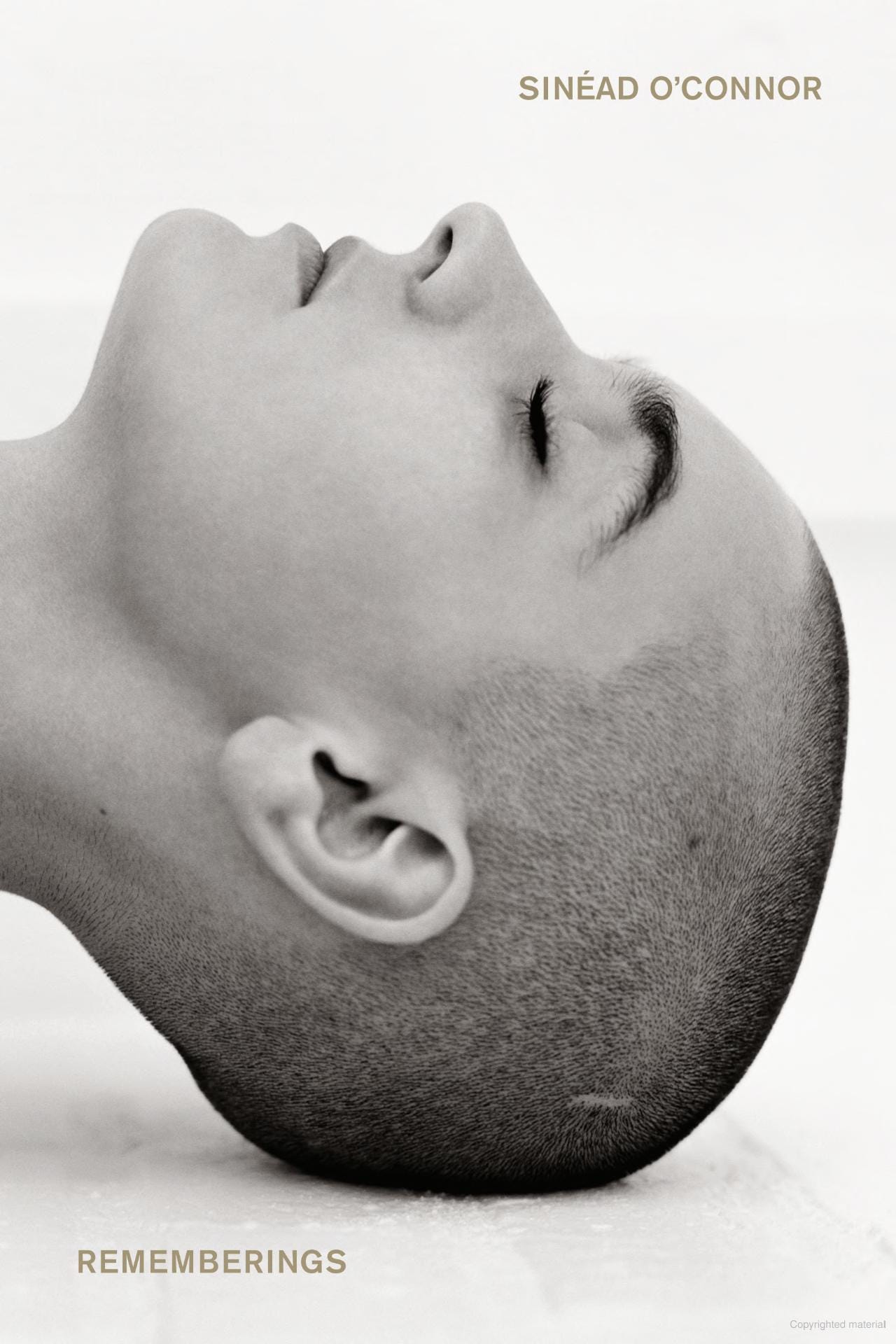

“Rememberings”

When O’Connor published her autobiography in 2021 it became a best seller and got lots of positive reviews. It’s a great book, which I only read now that she is gone. As I suggest above, there is probably no better time. And obviously it’s the best way to get to know her and to understand, from her perspective at least, why she did so many of the things she did.

O’Connor writes a lot about her early childhood and how she was abused by her mother, physically and emotionally, which obviously helps explain a lot of the struggles she faced throughout her life. Her mother was killed in a car crash in 1985. (The same year my mother died from complications of breast cancer.) This was before she was famous, before she became a star. I don’t need to tell anyone the effects of unresolved issues with a parent who dies before peace and forgiveness can be achieved.

In the beautiful video for “Nothing Compares 2 U,” there is a brief moment when a tear rolls down O’Connor’s cheek. In the book, she explains that this was not staged.

“…I just sang the song along with the track, sitting in a chair wearing a black polo neck. But in the part where it was ‘All the flowers that you planted, Mama, in the backyard, all died when you went away,’ I cried for like twenty seconds.”

One of my favorite chapters is called, appropriately, “Shaving My Head.” O’Connor describes how her first producers thought she needed to look more feminine and stop wearing her hair short. So she went to a Greek barber the next day and asked him to shave it all off. The barber begged her not to do it. “He held his hands as if in prayer,” and beseeched, “Yourh beeeeyoootheefil hayerh.”

“After I’d convinced him that I was the sole author of my own destiny, despite being female,” the barber agreed. “When he finished I stood up to face him, and one tear rolled down his right cheek.”

O’Connor’s account of how and why she ripped up the photo of the Pope on “Saturday Night Live” busts a few persistent myths. The photo had been on the wall of her mother’s home, she explains, and when her mother died O’Connor took it with her and kept it everywhere she lived.

“My intention had always been to destroy [it]… It represented lies and liars and abuse… I never knew when or how I would destroy it, but destroy it I would when the right moment came.” That right moment finally did come, the evening of October 3, 1992, on a very live SNL. She made the decision to do it just hours before the show aired.

She had been angry for a few weeks, O’Connor writes, because she had been reading a brutally honest history of the early Church, but also she was “finding brief articles buried in the back pages of Irish newspapers about children who have been ravaged by priests but whose stories are not believed by the police or bishops their parents report it to.”

And, she makes clear, she knew what she was doing.

“I know if I do this there’ll be war. But I don’t care. I know my Scripture. Nothing can touch me. I reject the world. Nobody can do a thing to me that hasn’t been done already. I can sing in the streets like I used to.”

Obviously, tearing up the photo of the Pope changed O’Connor’s life, how she was regarded in the music industry, by her fellow performers, and pretty much every way possible. But how others viewed it and how she viewed it herself were, on the whole, very different.

“A lot of people say or think that tearing up the pope’s photo derailed my career. That’s not how I feel about it. I feel that having a number-one record derailed my career and my tearing the photo put me back on the right track. I had to make my living performing live again. And that’s what I was born for. I wasn’t born to be a pop star. You have to be a good girl for that. Not be too troubled.”

There’s a lot more in the book, including a lot of setting the record straight. No, she did not refuse to perform if the “Star Spangled Banner” were played before the concert. She was asked how she felt about it and said she preferred it not be. No, a protest against her that included bulldozing her albums was not a success. The only two people who showed up to it were O’Connor in disguise (a long black wig) along with a friend.

Most of the rest of the book is about her albums, how they came about, commentary on the songs, and a lot about her children. And that’s what O’Connor leaves behind, really. A number of great albums, a few maybe not all that great, and three surviving children. The songs will endure, and with luck, the children as well.

The president of Ireland came to her funeral. There were lots of tributes. Assholes like Madonna and Miley Cyrus, who gave her a hard time when she needed love and support, have been silenced. She spoke out about her struggles, and was sometimes exploited when she was most vulnerable (here’s looking at you, Dr. Phil.)

I will die one day, and you, dear reader, will die too. But generations to come will still be listening to her music.

Sinéad O'Connor will live on.