Spirit of Place: The Romance of Route 66

In which a reporter, just before taking off to seek romance in Paris, takes to the old road one last time.

If I told you that I once sat in a cafe in a dusty California town called Amboy and daydreamed about Paris, you might not be surprised. The City of Light has long been the stuff of American dreams. But what if I said that I sometimes sat in Paris cafes and mused about Amboy? At such moments the bustle of the Parisian streets faded briefly from my consciousness, replaced in my mind's eye by this desert town on a lonely stretch of road that was once U.S. Highway 66.

In 1988, after spending most of my life in California, I married an Englishwoman and ran off to live with her in France. At least, in the excitement of radically changing my life, it seemed as though I were running off. Actually, I had to wait three months for my French immigration visa to come through. As I went about the business of winding up my affairs, my impatience to leave was tempered with sadness. I knew that I might never live in California again, and I wanted to say a proper goodbye to the place where so much of my life had unfolded. It was this desire that landed me, shortly before I left for France, in Amboy.

Route 66 had been a major conduit of my passage to adulthood. In 1965, as a freshman at UCLA with a shiny new motorcycle, it was the main route out of Los Angeles to the flaming cliffs and spires of the American Southwest. This was the first part of the U.S. that I discovered for myself, rather than from the windows of the family car. Yet for me and many other members of my generation who had come of age during the turbulent sixties, Route 66 was also the most elemental manifestation of "the road," a place as important for what it led you away from as for where it took you. My friends and I, inspired by the novels of Jack Kerouac, J.D. Salinger, and other chroniclers of youthful alienation, took to the highway as a rebellion against what we felt to be the numbing mediocrity of everyday life. It was a romantic notion, even if the road sometimes offered little more than the certainty that we could make our way home again.

In its heyday, U.S. 66 was the main thoroughfare from Chicago to Los Angeles. It began at the intersection of Chicago's Jackson Boulevard and Michigan Avenue, fell in a southwesterly arc through Illinois, Missouri, and a tip of Kansas, and dropped down to Oklahoma City. The road then headed west into the Texas Panhandle and through New Mexico, Arizona, and California before ending at the Pacific Ocean near the Santa Monica Pier.

It was a highway shaped as much by mythology as by asphalt and concrete. Mention Route 66 to any adult American, and you will certainly get a reaction--its nature will depend on which generation you are talking to. During the Depression of the 1930s, 66 was the route of westwards migration out of the Dust Bowl. The trek of the Okies, Arkies, and Texans to California was immortalized in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. "66," Steinbeck wrote, is the path of a people in flight, refugees from the dust and shrinking land...66 is the mother road..."

Boomers might think instead of the 1960s CBS television series Route 66, starring Martin Milner and George Maharis, who cruised the old road in a Corvette convertible looking for adventure. That program, a curious blend of film noir and soap opera, did much to seal the highway's reputation as a place where romantic fantasies of restlessness and rootlessness could be indulged. (I'm not quite sure what Route 66 means to today's younger generations, especially as the old road becomes increasingly commercialized as a tourist attraction. Nostalgia, after all, is a taste normally acquired by the aging and not indulged in by the youthful.)

But in 1985, transportation officials revoked the U.S. highway status of Route 66. The decision was the inevitable finale to a process that had begun in the 1950s, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed legislation creating the interstate highway system. Some of the interstates that replaced Route 66 were simply poured right over the old highway, and many of the remaining segments became bypasses for local traffic or were demoted to the lowly status of frontage roads.

Yet California retains some of the longest stretches of the original route, where the highway breaks free of the interstate system and charges off into the countryside with its lost honor restored, sullied only by crumbling, long-closed cafes and gas stations.

As I sat at my desk in Los Angeles, sending out change-of-address forms and filling out French immigration papers, I felt a strong yearning to get out on that highway one last time. I was motivated in part by nostalgia, to be sure. But I was also driven by that alarm you sometimes feel when an important memory is fading, a memory that is a chunk of your being and threatens to take part of you with it when it goes. I longed to recapture it, to shore it up against time's erosion, before it was lost completely.

On a cold December morning I climbed into my gray Datsun and took the freeway to Needles, on the California-Arizona border. My plan was to drive slowly back to L.A., using old auto club maps to help me cover every inch of that California portion of Route 66 that I could find. I stayed overnight at a Needles hotel and started out early the next morning, stopping for breakfast in Goffs, a one-cafe town with a population of about a dozen people. After Goffs, the highway crossed Interstate 40 and began what, in California at least, is the widest divergence between the original road and the spacious freeway that replaced it. The interstate disappeared off to the right, and the last I saw of it was the gleam of the sun on the white sides of distant trucks.

Although the road had lost its U.S. 66 marker shields, there was no mistaking it. A thin ribbon of highway, two narrow lanes and a faded single yellow line down the center, climbing and dipping, curving widely for no apparent reason, cutting through the desert.

I stopped as often as I could along the route, talking with the people I met and trying to figure out why they were still out there. The opening of the interstates had wiped out most of the businesses along Highway 66, and I was surprised at the tranquility with which some people still hung on. In a forlorn place called Essex, which once had four gas stations but now had none, I spoke with Mary Howard, who grew up in the town and was still teaching in its single-story schoolhouse. Her husband, Jack, came to Essex from Oklahoma in the 1950s and later became the town's postmaster. I asked Mary what had kept her there for so long.

"I like the wide open space," she said. "I get disoriented when I can't see a lot of sky around. When I go to Oklahoma to visit my husband's family, all those trees make me nervous. I feel closed in. I like a lot of nothing."

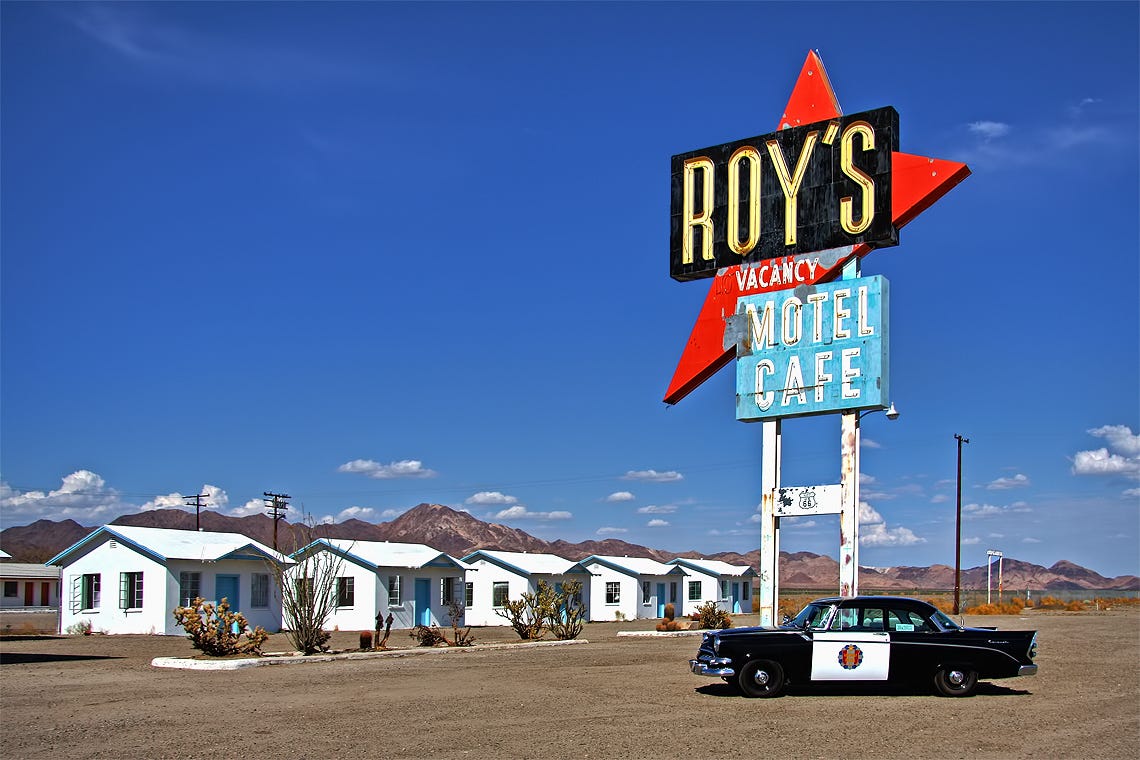

It was four o'clock in the afternoon when I got to Amboy. Almost everyone I had met along the road had told me to look up Buster Burris when I got there. Sure enough, as I walked through the front door of Roy's Cafe, Buster was sitting at the counter in an olive drab mechanic's jumpsuit. He half-looked as though he were expecting me. It was almost closing time, but Buster told the waitress to leave the coffee on.

Buster grew up in San Antonio. He worked as a pilot and an aviation inspector, first in Texas and later on at an Air Force base near San Bernardino, California. It was there that he met his first wife. Her father, Roy, after whom the cafe was named, came to this area in 1925 to work at the nearby salt mines. Later he bought some 50 acres of land straddling the railroad tracks at Amboy, and he persuaded Buster to help him build an auto garage on the highway. Later they built a bigger garage and turned the first one into the cafe.

Buster's thick white hair was combed back from his leathery forehead. His hands were brown and rough, and the longer fingers ended in jagged nails. "We had so many cars coming in here we'd be working until midnight, and when we'd come back the next morning, they'd be lined up again. We worked 90 people here, running the cafe 'round the clock, three shifts, 24 hours a day, three and sometimes four waitresses, cooks, dishwashers."

As the business grew, so did Amboy. Buster and Roy built many of the town's buildings, including the church and the post office. When Roy died, Buster carried on. Then, in 1972, the interstate opened.

"It hit me the first day," Buster said. "There wouldn't be more than two or three cars coming by. There were thousands before. It's hard to believe. I figured I had a three or four million dollar investment, and that just killed it. They said, 'That's what you get for building on a highway.'"

Buster cut the cafe back to one shift. The restaurant had not closed its doors for almost 30 years, and when he went to lock it up, he couldn't find the key. He had to call a locksmith to come out and make a new one.

As we were talking, the desert sky began to turn dark. Buster pointed out the window to the road that led south to Twentynine Palms. "See those car lights?" he asked. "That one will be here in 10 minutes, and that one in 30. The nice thing about living here is that you can see a long way away. It was almost my desire, when I was younger, to start a town and stay with it, build it up, see if it could be done."

Buster drank the last of his coffee. "The moment this road was turned over to the county, all the Route 66 signs were taken off. But people still know it as 66. It'll always be that."

I stayed overnight in Buster's motel, and the next morning I drove out of Amboy. Before long, the interstate came into view again, a giant gray snake slithering through the desert sand. Route 66 had run free for a long stretch, but now there was no place to go. Feeling angry, and a little silly, I followed what was now a frontage road. Cars and trucks whizzed by me on the interstate. The moan of their engines filled my head and made it feel heavy.

I wasn't against progress, not really. I knew that the pulse of modern transportation couldn't flow through the slender veins of a two-lane highway. But the demise of Route 66 threatened the part of me that had grown up on that road, the part that needed to know there was an escape, a way out, when my life turned sad and troubled.

For a while I let my mind drift back to an earlier time, when I didn't know what the future held or what I really wanted. Out on Route 66 there was time and space to dream, and despite all that was awaiting me--life with someone I loved in a beautiful foreign country--it was still jarring to find the constraints of adulthood wrapped around me once again.

The next day, I was back in my Los Angeles apartment, packing boxes and planning a garage sale. The highway had served its purpose: It had brought me home again, which is all you can ask of any road. Even now, though the center of my universe has shifted thousands of miles away, I sometimes find my mind drifting back to Amboy and Buster's cafe and that little ribbon of road that wanders through the California desert. I suppose a part of me will always be driving down that highway, glancing in the rearview mirror now and then at the places I've left behind.

Afterword: Buster Burris died in 2000 at the age of 91. I'm still married to the Englishwoman.

Note: This article is adapted from an article I published in National Geographic Traveler in 1996. It was in turn adapted from an earlier and longer piece in the now-defunct L.A. Reader. Of course, many, many writers have tackled the subject of Route 66, and I cannot claim that my own take is any better (or worse.) But it is my take, and I hope it brings readers some pleasures. I expect the longer version of this story to be part of a book I am currently working on, entitled "Islands and Other Places: The Journeys of an American in Exile."