The camera lies, but it also tells the truth: Photographs of the Catholic Church's sex crimes "scandal"

A powerful exhibition in Boston by photographer Lisa Kessler, "Heart in the Wound," probes the damage of crimes committed by priests, who abused their trust to hurt children.

“This is like a lot of photographs. It tells a lot of truth, and it tells a lot of lies.”

Of the 18 photographs currently on view at Lisa Kessler’s exhibition at the Howard Yezerski Gallery in Boston, titled “Heart in the Wound,” the one above struck me the hardest. On the left, smiling and seemingly self-satisfied, stand the lawyers for the Archdiocese of Boston and its Archbishop, Bernard Law; on the right, a small figure tucked into the corner of the frame, with body language suggesting a defensive crouch, is Mitchell Garabedian, attorney for victims of pedophile priests. The photograph seemed to have the same effect on some family members who had come to the exhibition with me, and who, also like me, have been friends of Lisa’s for many years. There is David on the right, and the Catholic Church’s Goliaths on the left, an image that powerfully evokes the social justice struggles many of us have fought for so much of our lives.

Lisa took this photograph in August 2002, after spending much of the 1990s working as a photographer for the Archdiocese, including for its official newspaper. The previous year, Law and the Archdiocese became defendants in more than 80 lawsuits for covering up the crimes of John Geoghan, a pedophile priest who was moved from parish to parish over many years as accusations of abuse followed him. The story, originally broken by Kristen Lombardi of the Boston Phoenix, was later picked up by the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” investigative team, whose investigations were the subject of two films which brought the scandal to a wide international audience: “Our Fathers” in 2005, and “Spotlight” ten years later (Ted Danson played Garabedian in the first film, and Stanley Tucci in the second.)

Lisa was no longer working for the Archdiocese newspaper when news of the crimes broke. (Lisa, rightly, prefers the term “crimes” to the neutral, non-committal fudge word “scandal.”) But her empathy for, and support of, the victims and survivors, and her close acquaintance with Law and other staff of the Church, allowed her rare access to most everyone involved. The Archdiocese allowed her to photograph Law and other key figures as long as the images did not become part of the daily news cycle.

Lisa took the photograph above during a break in a hearing on a proposed settlement of a lawsuit by more than 80 victims against the Archdiocese and Geoghan, who by then had been defrocked by the Church. The Archdiocese had initially offered $30 million to the victims, but had reneged on the agreement when its financial counselors said it could not afford it. Law was forced to testify during the hearing, and he bristled in anger and humiliation as Garabedian grilled him in front of a full courtroom.

“This is like a lot of photographs,” Lisa told me. “It tells a lot of truth, and it tells a lot of lies. People are seeing me, and they know I am there with the camera,” perhaps 10 to 15 feet away. “They all know me, and they are all comfortable with me.” Lisa worked with a small, unobtrusive Leica camera, quiet with no flash, using high speed film that gave a graininess to the image. “I always took a neutral stance.”

I told Lisa that the lawyers facing the camera, who included Law’s long-time attorney Wilson Rogers, Jr., on the far left, and his two sons who worked in the family law firm, appeared to me to be smirking arrogantly. But she saw it differently. Rogers had always refused interviews and kept a very low profile. Attorneys interviewed by the Boston Globe about him said he was a good man. Rogers had difficulty believing that these allegations were true, the Globe reported. But when he did, he was very careful not to re-traumatize people. He was torn up as well.

Nevertheless, Lisa agrees, the Church and its attorneys did huge damage to victims by covering up the crimes for so many years. In her photographs, despite her own uncompromising support for survivors and condemnation of the coverup of the abuse, Lisa tried to capture the nuances and ambiguities of what was at heart a human tragedy.

As for Garabedian, Lisa said, even though he was definitely the underdog, we should not be fooled by his body language. In that sense, Stanley Tucci’s curmudgeonly portrayal of him in the film “Spotlight” was perhaps closer to the mark. “Garabedian’s approach was to put the victims out in the front of the press, try the case in the court of public opinion. That was a huge conflict between the two sides.” Law and the Archdiocese clearly thought that Garabedian was being unfair, because—in the case of Geoghan—the Church had sent the priest to doctors who certified that he had been rehabilitated. The truth, however, was that the doctors the Church employed had no qualifications regarding sexual predators. “The Church didn’t do its due diligence because they stayed within their own bubble,” Lisa said.

That’s what Garabedian was able to demonstrate. “This is again how photography lies and tells the truth.” Lisa said that she did not originally consider including this image in the exhibition, because she thought it was a very unflattering and inaccurate depiction of Garabedian—who, after all, had won the battle. But when the gallery owner, Howard Yezerski, saw it, he insisted that it had to be in the show.

“He saw this as a very important photograph.” David had beaten Goliath. I asked Lisa if, by finally agreeing to have the photograph in the exhibition, she was indulging what I and others saw in the image, even if it was not entirely accurate. “No photograph tells an exact truth. My photographs capture candid moments that are moving you towards an emotion, they are slices of a moment in time. I have to accept those ambiguities. I have captured them in a moment to create a metaphor. It’s been hard for me to accept it, but what I have to say in this body of work” is more important than the “scientific accuracy” of the images.

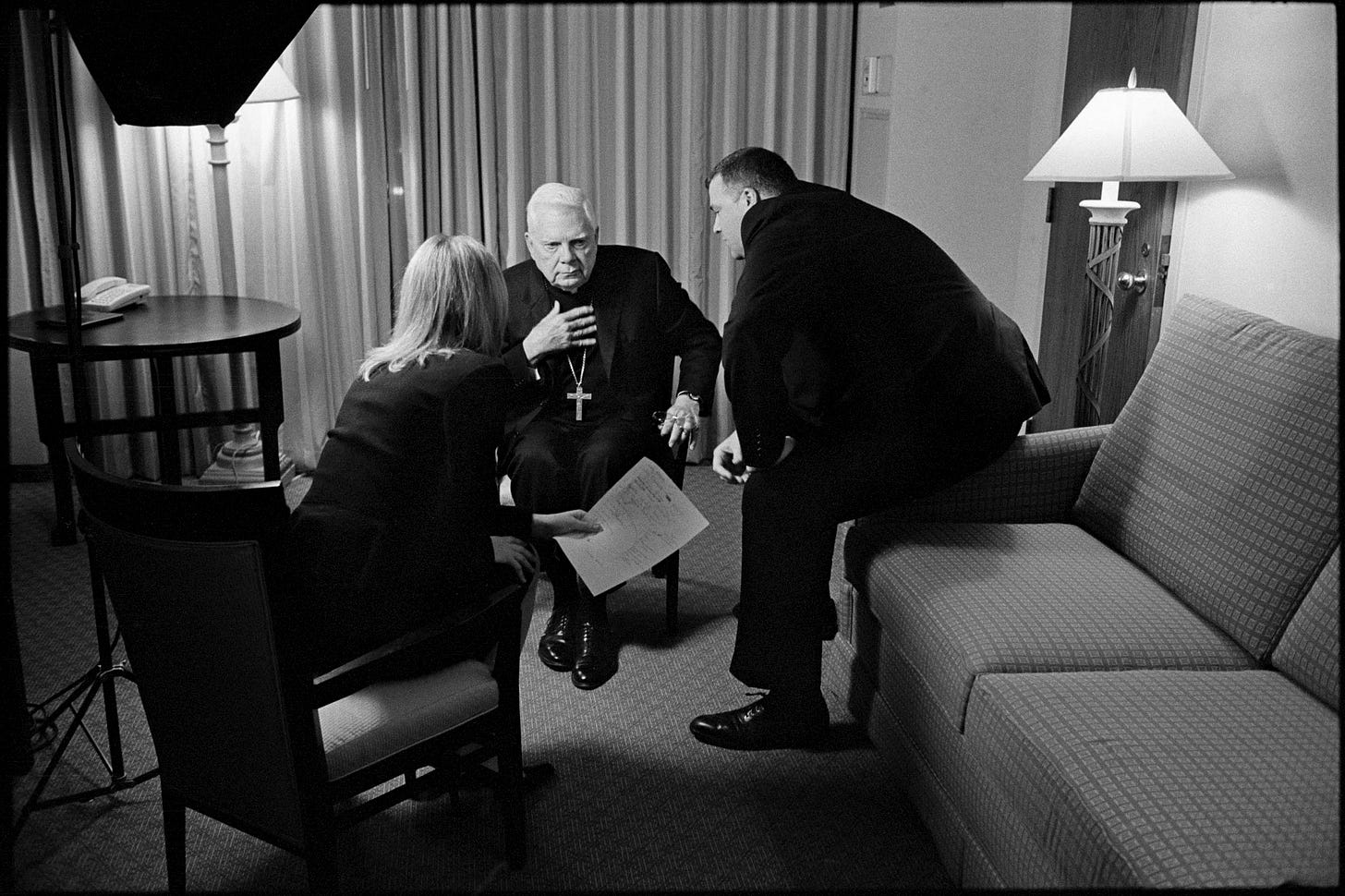

This photograph was taken in November 2002 in Washington DC, at the National Bishop’s Conference, the second one that had taken place after revelation of the crimes. Law, like the rest of the Catholic Church, protected his priests and not the accusers. “The survivors coming forward and being believed, and people accepting that priests had hurt children,” Lisa said, was a huge breakthrough. “The documents had revealed over and over that Law had reassigned, sent them to be treated, the stories were grotesque. It was not a few bad apples.”

By this time, the story was all over the national media, but Law was still surviving intense pressure to resign. He had been to the Vatican, which supported him staying in office; but by the time of the conference, reporters were insisting on interviews and photos. Here he is in a room in the hotel where the meeting was held, huddling with his advisors either in between the interviews or just before (Lisa does not recall which it was.) The press were coming in one at a time, and Lisa was allowed to be there. A month later, he resigned.

“They are talking about the message, and keeping him on message. It was a very intense moment. He is struggling, he is in bad shape. He’s trying to hold it together and be father of the Church, but people are not happy.”

When I first saw this photograph, I jumped to the conclusion I think a lot of other viewers may have as well: This was a grown man, holding a photograph of himself as a boy, when he was abused by a priest.

But Lisa told me that she didn’t know if that was the case. The man was participating in a demonstration against clergy abuse, and this was a quick shot that captured a moment in time. “The activists had these posters, sometimes victims carried them themselves, or sometimes an activist would give them the sign.” This one might depict the man as a child, but there is no way of knowing.

And what about the look of determination on his face, the set jaw, the pain he is showing, along with a certain resigned acceptance that there is so much evil in the world?

“He’s there,” Lisa said. “Whether he is a victim, or he knows victims, or he is an activist, I feel that it doesn’t matter now. Maybe he’s pained because this was his fucking Church and he had no idea that this was happening. He was there and out in public taking a stand, holding a photograph of a child who was abused by a priest. That’s the bottom line.”

The exhibition is on view until March 26. If you are in Boston, or can get to Boston, I urge you to go see it. It’s a small show, in a small space, but its themes and concerns are as big as humanity itself, and the desperate, terrible pain we are capable of visiting upon each other. I am hoping that these photographs, and more of the thousands that Lisa took during a “scandal” that has only grown bigger over the past 20 years, will soon find an even wider audience.

This post provides a powerful and moving perspective on a disgraceful and saddening issue. While individual priests who exploited their positions to commit such crimes are seemingly rare, it beggars belief that the Catholic hierarchy did not act swiftly and decisively to protect their flock from such dreadful transgressions.