The Covid-19 pandemic: Failure to predict, failure to report. Part Two -- Attack of the killer preprints (I)

More than a half dozen studies have been put online challenging key claims of the natural origins hypothesis for Covid-19 origins. In this installment, we take a look at them.

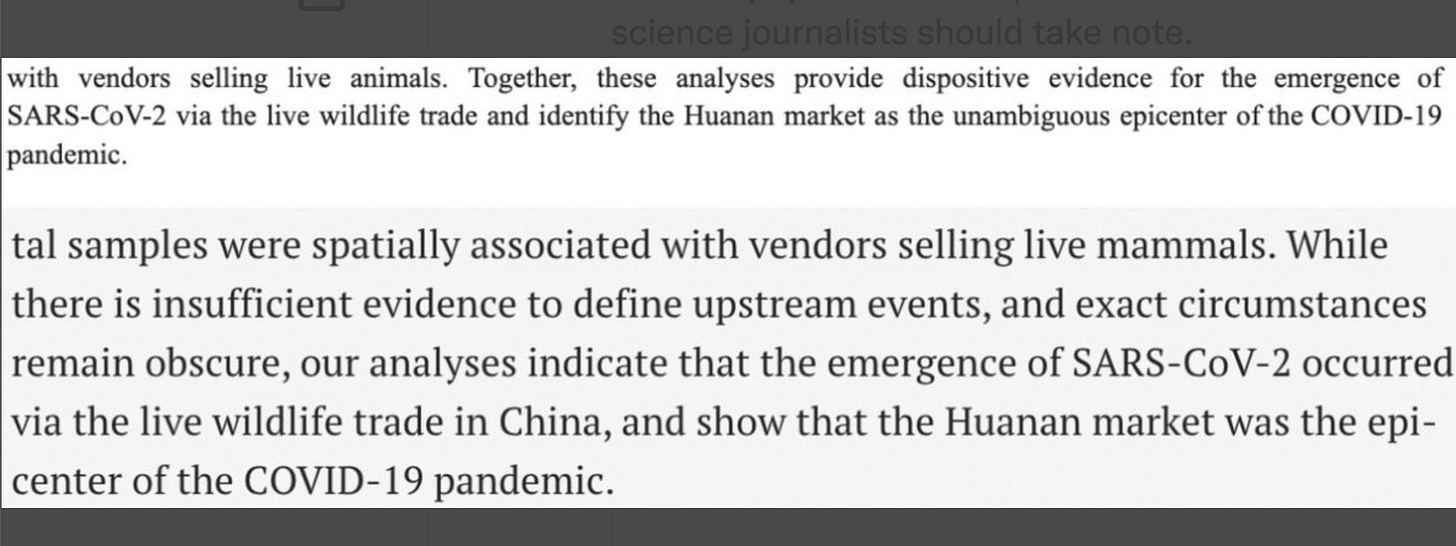

Last February, two research teams with overlapping sets of authors posted online two “preprints”—scientific studies not yet peer reviewed—arguing that the Covid-19 pandemic began at the Huanan “seafood” market in Wuhan after a coronavirus jumped from one or more animals to humans. One of the studies concluded that there had been not one, but two, such “zoonotic transfers” at the market. The authors stated that they were very sure of their findings: Indeed, one of the preprints declared that the evidence for the conclusions were “dispositive.”

But last month, a number of research teams posted their own preprints about these conclusions, critiquing them from a number of angles. Some argued that the statistics used by the two research teams may have been flawed. For example, researcher found that when alternative statistical approaches were employed, the “epicenter” of the pandemic shifted to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which some scientists think was the actual source of the pandemic after a lab leak or other accident. Another team concluded, using the original authors’ own data and computer code, that the origins of the pandemic were more closely localized in the toilets at the Huanan market (used by humans and presumably not by animals) than with stalls where wild animals were sold, as the original studies had found.

At about the same time, yet another team posted a preprint arguing that the Covid-19 virus, SARS-CoV-2, had genetic signatures suggesting that it had been engineered in a lab. And on October 28, molecular biologist Alina Chan of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, a leading critic of the natural origins hypothesis who has called for a thorough investigation of the question, posted a preprint of her own study critiquing the market origins hypothesis, which she had been trying to get published for more than two years.

In this post, I will go over all of these preprints—most of which have yet to receive media attention or much social media discussion—in some detail. I hope this will be a service to readers who are still trying to figure out not just what scientists are saying, but what the science might be saying. But first, a little history and context.

“Breaking news:” The debate over Covid origins is over (maybe.)

I found out about the February preprints, which have had such a major impact on the discussion over Covid origins, because, as a New York Times subscriber, I receive “breaking news” alerts both by email and text. I can’t recall the last time that the Times issued such an urgent alert for research that had not yet been vetted by other scientists; perhaps this was the first time ever, but I hope readers of this newsletter can help out with the question. Any any rate, the article, by reporters Carl Zimmer and Benjamin Mueller, heavily implied that the long-running debate over the origins of the pandemic might be drawing to a close.

“When you look at all of the evidence together, it’s an extraordinarily clear picture that the pandemic started at the Huanan market,” said Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona and a co-author of both new studies.

Several independent scientists said that the studies, which have not yet been published in a scientific journal, presented a compelling and rigorous new analysis of available data.

The first version of the story (see below) was very short and allowed little doubt that the researchers had nailed the origins of the pandemic. In a later expanded version of their report, the two reporters did go on to discuss some reservations expressed by a couple of scientists, and gave some attention to a third preprint, posted online just before, by a Chinese team led by the then-head of China’s CSDC, George Gao. That study concluded that the market was not the original source of the pandemic, but the site of a “super-spreader” event. The conclusion of the Chinese scientists was that the virus had been brought into the market by one or more humans, not by animals.

The Gao preprint has received little to no attention from mainstream media reporters since. Instead, word of the two preprints (referred to as Worobey et al. and Pekar et al.) spread rapidly throughout the news media, along with the message that the origins question was largely solved.

In July, after five months of peer review, Worobey et al. and Pekar et al. were published in Science. (The Gao study, reportedly in submission at Nature, remains unpublished. Gao told me in an email a few weeks ago that it was “still under submission” and that he could not tell me more.

In their published form, the Worobey and Pekar papers had undergone some important revisions. Most notably, the “dispositive” language had been removed, and the papers acknowledged—as is standard scientific practice—that they had limitations and were not necessarily the last word on Covid origins.

Here is an example of the changes (courtesy of, and thanks to, @HansMahncke. The top image is of the preprint language, the bottom the final published version:

(I will do a couple of posts about the media’s coverage of the Covid origins story later, but suffice to say for now that the Times did not update its story after the two papers were published with significant revisions.)

Alina Chan, who along with other scientists has raised many questions about the natural origins hypothesis, published a commentary on the papers on Medium, entitled “Evidence for a natural origin of Covid-19 no longer dispositive after scientific peer review.”

Chan began with a critique of the initial media coverage:

“The NYT journalists who covered these preprints were so eager to report the then not-yet-peer-reviewed findings that the first online version of the story was only a dozen sentences long and only quoted the lead author of the preprints. The story was featured as front page breaking news on the NYT website just as the Ukraine war was unfolding.”

As for the scientific conclusions, Chan commented:

The peer-reviewed paper has an entirely new section on “Study Limitations” which acknowledges that the scientists do not have access to the early Covid-19 case data or locations, lack direct evidence of a market animal infected with the pandemic virus, and lack complete details of how the market had been sampled for the virus.

Despite lacking access to data, Worobey et al. 2022 surprisingly claim in their preprint and the peer-reviewed paper that “positive environmental samples [were] linked both to live mammal sales and to human cases at the Huanan market.”

Nevertheless, since they were published in July, the two papers have been cited repeatedly, in articles about Covid origins and on social media, as a supposed final rejoinder to any doubts that the pandemic was due to a zoonotic transfer, and any suggestions that the lab-leak hypothesis continued to be a viable hypothesis. Indeed, some natural origins proponents have developed the habit of posting the papers on Twitter in response to posts from lab-leak advocates, without comment. It’s as if they have become more than just scientific papers, subject to debate and criticism just like any other research, but some kind of magic amulets with the power to banish the evil spirits of contrary views.

I will discuss those evil spirits (ie, preprint challenges) to the Worobey and Pekar papers shortly. But first, let’s begin with the latest breaking news: The media flap over claims that the virus shows signs of genetic engineering. I will keep this section fairly short, since there has been a lot of media coverage and it’s the topic readers of this newsletter are most likely to be already familiar with.

The tell-tale restriction sites: Did a genetic engineer leave their signature behind?

The Tweet above is by Kristian Andersen, a Danish evolutionary biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. In March 2020, just as the deadly pandemic was rearing its ugly head, Andersen and four other scientists published a now famous (or infamous, in the view of some) paper in Nature Medicine entitled “The proximal origins of SARS-CoV-2.” The paper, following an equally famous letter published the previous month in The Lancet branding the lab origins hypothesis a “conspiracy theory,” helped set the scientific and political tone for the origins debate. (The behind the scenes role of Anthony Fauci, Francis Collins, and other public health leaders in the publication of the “Proximal origins” paper has been discussed extensively elsewhere.)

For our purposes, the important part of the “Proximal origins” paper is its conclusions about the possibility that the pandemic virus could have been engineered. Here is the salient passage:

“It is improbable that SARS-CoV-2 emerged through laboratory manipulation of a related SARS-CoV-like coronavirus. As noted above, the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 is optimized for binding to human ACE2 with an efficient solution different from those previously predicted7,11. Furthermore, if genetic manipulation had been performed, one of the several reverse-genetic systems available for betacoronaviruses would probably have been used19. However, the genetic data irrefutably show that SARS-CoV-2 is not derived from any previously used virus backbone20.”

[Note: RBD = receptor-binding domain. ACE2 = the receptor to which the virus binds before entering human cells. Betacoronaviruses = the genus of coronaviruses to which SARS-CoV-2 belongs]

From the very beginning, the logic of this argument had been challenged by some other scientists, on a number of grounds. One of the most important, in my view, is the authors’ assumption that they know which virus backbones were “previously used.” As many have pointed out, the Wuhan Institute of Virology has refused to divulge exactly what work they were doing leading up to the pandemic, including precisely what virus backbones they had on hand or had engineered (it is indisputable that researchers at the WIV had a large store of SARS-like virus samples and were creating recombinant and chimeric versions to study their properties.)

Moreover, to their credit, Andersen and his colleagues did not claim their analysis of the virus was the final word, despite the vitriol of Andersen’s recent Tweet pictured above:

“More scientific data could swing the balance of evidence to favor one hypothesis over another.”

On October 20, three researchers—Valentin Bruttel, Alex Washburne, and Antonius VanDongen, posted a preprint that might be seen as the opening shot in the grand reopening of the Covid origins debate: “Endonuclease fingerprint indicates a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2.” I think the “Lay summary” of the paper is very clear, and so I will quote it entirely here:

“Lay Summary To construct synthetic variants of natural coronaviruses in the lab, researchers often use a method called in vitro genome assembly. This method utilizes special enzymes called restriction enzymes to generate DNA building blocks that then can be “stitched” together in the correct order of the viral genome. To make a virus in the lab, researchers usually engineer the viral genome to add and remove stitching sites, called restriction sites. The ways researchers modify these sites can serve as fingerprints of in vitro genome assembly.

We found that SARS-CoV has the restriction site fingerprint that is typical for synthetic viruses. The synthetic fingerprint of SARS-CoV-2 is anomalous in wild coronaviruses, and common in lab-assembled viruses. The type of mutations (synonymous or silent mutations) that differentiate the restriction sites in SARS-CoV-2 are characteristic of engineering, and the concentration of these silent mutations in the restriction sites is extremely unlikely to have arisen by random evolution. Both the restriction site fingerprint and the pattern of mutations generating them are extremely unlikely in wild coronaviruses and nearly universal in synthetic viruses. Our findings strongly suggest a synthetic origin of SARS-CoV2.”

For readers who want more details and context, I would also highly recommend this very clear and well done piece by Karolina Corin and Emily Kopp for the advocacy group U.S. Right to Know.

As noted above, the study has come under virulent attack by scientists who strongly favor the natural origins hypothesis, although some researchers have expressed their reservations in more collegial terms. The authors, while defending their work, have also clearly been open to input, and to the possibility that their findings are wrong—although in recent days they have performed a number of additional calculations that make them even more confident in their conclusions.

An interesting side story to this preprint is how it managed to attract the significant amount of media attention it has. Coauthor Alex Washburne, who was emerged as the spokesperson for the group, managed to convince science writer Natasha Loder and her editors at The Economist to do a story. That this venerable publication would lend its prestige to the idea that the study should be taken seriously not only helped give it legs, as it were, but also contributed to the somewhat frantic over-reaction of natural origins proponents (the Tweet from Kristen Andersen above was just the first in a series of posts that were highly insulting to the authors. Another example:

One good result of these over-the-top (and, I would argue, highly unscientific) reactions to the preprint has been a renewed discussion of the need for civility in scientific discourse, a principle that both sides of the argument often ignore (with some notable exceptions, Washburne and Alina Chan being among them.)

Another part of the side story is that Washburne has emerged as a sort of gentleman philosopher of the Covid origins dispute, with a series of posts on his Substack newsletter, “A Biologist’s Guide to Life.” His post from September 27, before the war over his preprint broke out—entitled “How to investigate SARS-CoV-2 origins”—is particularly good on the ethics of scientific debate, and I highly recommend it. Before moving on to the preprints challenging Worobey and Pekar, I will leave readers with this excerpt:

“As we turn over stones, we need to be very careful to not tarnish reputations of our colleagues without strong evidence. However, at some point, the lack of cooperation, the defensive attacks and poor transparency from researchers constitutes a violation of scientific trust, a violation of their ethical duties as scientists to help our world of scientists uncover the truth. While science involves considerable peddling to claim your work is amazing and get everyone to pay attention to it, at some point it is unethical to use one’s authority as an expert in a field to present speculations as facts in a way that prevents people from finding the actual facts. It is unethical to call competing hypotheses “misinformation” and exclude their existence from the public domain. It is unethical to publish papers with hollow arguments and run those papers to media outlets for widespread dissemination and false claims of scientific consensus intended to sway the public while steamrolling over the skeptical scientists who don’t agree.”

Please see the next post for the continuation of this topic!