The dreaded spotted lanternfly is too pretty to squish. Do we need to rethink our attitude towards "invasive species"?

We use the same rhetoric to talk about invasive species as we do "illegal immigrants." But the concept is problematic. Some researchers think science should take precedence over moral righteousness.

“Suppose they gave a war and nobody came?”

This famous slogan of the Vietnam War anti-draft resistance was invented in 1966 by Charlotte Keys, mother of a U.S. soldier who refused to fight. It seems that some have adopted a similar stance in the “war” against the spotted lanternfly (called by some the “Asian spotted lanternfly” to refer to its ancestral roots in China, and just possibly to whip up anti-Asian racism against the pest.)

Cases in point:

— “In the Lanternfly War, Some Take the Bug’s Side,” in the New York Times, features numerous quotes and large photos of conscientious objectors (including that of a Temple University student who nevertheless told the paper that she “keeps her warm feelings for lanternflies mostly to herself.”)

— A Substack newsletter post by one of my former New York University science journalism students, Ryan Mandelbirder (as he calls himself): “why does something so cool gotta be so bad.” Ryan includes all kinds of cool sciencey details in his post, including the damage they can do to agriculture (the bug apparently has Long Island grapevines clearly in its sights), and makes some interesting ecological observations and suggestions about how we might get rid of the insect.

But clearly, Ryan’s good heart is not into the genocidal eradication program urged by agricultural authorities, along with U.S. Senator from New York Chuck Schumer, who put out a screaming press release earlier this month:

“…the rapid spread of the invasive Spotted Lanternfly threatens to suck the life out of our vineyards, agriculture, and great outdoor tourism industry. We need to stomp out this bug before it spreads, otherwise our farmers and local businesses could face millions in damage and an unmanageable swarm.”

But just two days earlier, columnist James Barron of the New York Times threw some cold water on this kind of fiery rhetoric, in a post entitled “Trying to Stop Lanternflies? ‘Don’t Bother, They’re Here.’”

I don’t have any reason to doubt the economic damage lanternflies might do to agriculture, although it would be a good idea if some erstwhile journalists (including, but not restricted to, science writers) looked into the claims. Having cut my teeth as a reporter in Los Angeles during the Medfly wars of the 1980s, when agriculture officials insisted on spraying the pesticide malathion on urban populations and California health officials insisted that this well-studied neurotoxin was safe even for pets and babies (who were nevertheless supposed to be kept indoors), I have learned to be skeptical of all such militaristic eradication campaigns.

So far, at least, local authorities in New York and elsewhere are not spraying insesticide over us, although who knows what secret plans they may have. But it should be obvious that what they are telling us to do—mainly, squish every single one of these prettily colored beasts we see, and wipe out their gray egg masses—is unlikely to make a serious dent in the population numbers of an insect that seems to have found a very nice niche for itself along the East Coast.

Charles Darwin could have told us this, if he were still alive.

What we talk about when we talk about “invasive species.”

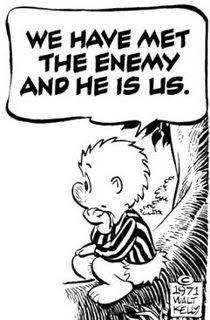

It could be argued that the invasive species that has caused the most damage in the world is Homo sapiens (or, as the cartoon character Pogo put it so long ago, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”)

Indeed, as humans spread over the globe, we brought with us all the invasive species we thought we needed for our survival. Horses, cows, pigs, chickens, among the animals, and wheat, rye, barley, and corn, among the plants, are all early examples going back to early prehistoric times.

Of course, as masters of the Earth and (we think, pretentiously) the universe, we humans take it upon ourselves to decide which species to call “invasive” and which to call our friends, depending on whether or not they benefit us personally. That’s one reason that some scientists have begun questioning the moralistic tone of the invasive species concept.

One early and widely cited dissident is Mark Davis, a biologist at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, who in 2011 teamed up with 18 other ecologists to publish a commentary in Nature entitled “Don’t judge species on their origins.” Davis and his colleagues criticized what they called “a pervasive bias against alien species that has been embraced by the public, conservationists, land managers and policy-makers, as well as by many scientists, throughout the world.”

Today, with Donald Trump and the GOP leading a racist movement against immigrants, asylum seekers, and other humans deemed “aliens” (that is, outsiders, representative of the dreaded Other), the language and rhetoric of “invasion biology” should give us pause. In their Nature piece, Davis et al. provided a number of examples of where this “native-alien” dichotomy was misleading. One example is the pine beetle, native to North America, but thought to be killing more trees than any other insect. Moreover, they argued, the goal of eradicating non-native species often ends in failure. Thus, at the time they wrote, of the 30 planned efforts to eradicate non-native species from the Galapagos Islands, only 4 had been successful.

More recently, some scientists have repeated and updated the call to change the language we use to describe non-native species, and even to throw out the term “invasive species” entirely. One notable example was published in 2020 by Meera Iona Inglis of Newcastle University in the United Kingdom, in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. In her article, entitled “Wildlife Ethics and Practice: Why We Need to Change the Way We Talk about ‘Invasive Species’” (Open Access), Inglis called for abandoning the term “invasive species” entirely. Her arguments are nicely summed up in the paper’s abstract:

“This article calls for an end to the use of the term ‘invasive species’, both in the scientific and public discourse on wildlife conservation. There are two broad reasons for this: the first problem with the invasive species narrative is that this demonisation of ‘invasives’ is morally wrong, particularly because it usually results in the unjust killing of the animals in question. Following on from this, the second problem is that the narrative is also incoherent, both from scientific and philosophical perspectives. At the heart of both of these issues is the problem that the invasive species narrative oversimplifies what are in fact very complex biological processes. As a result, the policies carried out with the stated aim of ‘controlling’ these animals are often unethical. In light of the current global species decline, this article asserts that the way we think and talk about these animals should be changed and the term ‘invasive species’ should be discontinued, in the hope that this leads to changes in practice.”

(For a good survey of this new thinking and suggestions for further reading, I recommend this 2018 piece in The Smithsonian, “Why We Should Rethink How We Talk about ‘Alien’ Species.”)

Interestingly, just this month, the New York Times ran two stories in its Science section about cases in which “invasive” species have turned out to be ecologically helpful (see here and here.)

Of course, despite all this new thinking, there is no question that some species, whether native or non-native, can wreak havoc with plants and animals that we value and favor for our own survival as a species (or, in the case of the spotted lanternfly’s attack on Long Island vineyards, value for our cultural comfort.)

And sometimes we can do something about it without wreaking havoc of our own, for example by dumping toxic pesticides over urban areas or spraying herbicides like glyphosate (now shown to cause a number of health and environmental problems) over our crops to get rid of “invasive” weeds. But in many cases—and the spotted lanternfly may turn out to be one—it’s a hopeless battle, and all of our moral fervor will not help turn the tide.

If we want to get moralistic about our earth’s fragile ecology, perhaps the most important place to start is with what we can do to slow the anthropogenic climate change that we, the most devastating “invasive species” in the history of the planet, are solely responsible for. I think that poor Pogo would really appreciate it.