Welcome to Earworm Wednesday!

In this new semi-regular feature, "Words for the Wise" explores the earworm of the week, and thoughts about why it won't go away. Consider it cultural commentary, please.

As regular readers of “Words for the Wise” know, any promise of a “regular” feature needs to be taken with a grain of salt, given the irregular posting schedule of this newsletter. I am well aware that I violate all of the advice Substack gives to its authors, such as stick to one subject and publish on a predictable schedule like the New York Times does.

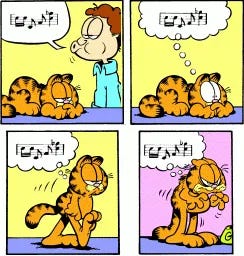

Fortunately, most of you do not seem to hold that against me, probably because you are the wise souls this newsletter is meant for. You know that the biggest killer of inspiration is the obligation to be inspired at a given day and time. Nevertheless, I am announcing, with some trepidation, a semi-weekly feature (meaning it will not necessarily be every week) I will call “Earworm Wednesday.” In this first installment, we will get the science of earwormery (technically known as Involuntary Musical Imagery) out of the way, as fascinating as it is; in future segments, I will write about earworms I have known (I always have at least two or three on the go at any time) and what I think they might mean to me and to others.

My own keen interest in earworms dates back to the spring of 1986, when the old song “September in the Rain” got into my head and would not get out. My brain focused on one phrase of the song, which played over and over and over:

“Though spring is here, to me it's still September

That September in the rain”

It took a whole week of repeat play before I suddenly remembered, in a revelatory flash, that my mother had died the previous September and I was obviously still mourning her. So while some of the scientific literature treats earworms as some kind of cognitive aberration—and earworms can certainly be very annoying, unless you embrace them as we do with dreams and even hallucinations, knowing that they are trying to tell us something—I have tried over the years to decipher their meanings. Such meanings are, of course, very personal, but I think it likely that many of us actually get the same earworms, implying the possibility of some kind of universal meaning. Certainly, music is a kind of language, as much in the melody as in the lyrics. At the very least, it is something that we humans share.

Before I go on to the science, I shall reveal my current earworm, which I will talk about next week: Jackson Browne’s “These Days,” a sad song of wistful regret he wrote when he was only 16 years old. It has been recorded many times, and I have been reinforcing it in my brain by listening to as many versions as I can find on YouTube. There are many great covers, along with a number of versions by Browne himself; but let me leave you with one you may not have heard, by the wonderful St. Vincent (Annie Clark.) Who knows, perhaps it will infect you too.

The science of the Ohrwurm

So, over the past week or two, I have done a deep dive into the scientific literature on earworms, reading at least a dozen key papers and a couple of reviews. For those wanting an overview, and who are not frightened by a little scientific jargon, I can recommend two good reviews. One, from 2018, was published in the journal Auditory Perception & Cognition by Philip Beaman at the University of Reading in the UK. (An accessible draft of the paper can be found here.) I know Beaman, because he is an expert in the area of working memory, a subject I wrote about for Science a number of years ago. Since we become conscious of musical fragments (and probably everything else we are conscious of) when they enter our working memory, earworms have been of great interest to working memory researchers.

The second review, from 2020, is by Lassi Liikannen of the University of Helsinki and Kelly Jakubowski of the University of Durham in the UK. Liikannen has been associated with earworm studies for many years, and readers might be interested in a short clip about his research:

Reading these reviews, it becomes clear that there are a number of threads in earworm research. Some scientists see it as an example of involuntary perceptions, similar to hallucinations or OCD, and think that studying earworms might provide some clues to those psychological “aberrations.” Others have concluded that, especially since studies show around 90% of Western populations studied report experiencing earworms, they are a normal part of psychology, what Beaman calls “business as usual” cognition.

I particularly liked Beaman’s review because he delved a bit into the history of earworms, as recorded in literature, before they became the object of scientific study. Thus Edgar Allen Poe, in his 1845 short story “The Imp of the Perverse”—one of my favorites, about our impulse to do the opposite of what is good for us—observed about the repeating tune: “Nor will we be the less tormented if the song in itself be good, or the opera air meritorious.”

Beaman also cites Mark Twain’s 1876 short story, “A Literary Nightmare,” which is all about an earworm (although no one called it that then:)

“I returned home, and suffered all the afternoon; suffered through an unconscious and unrefreshing dinner; suffered, and cried, and jingled all through the evening; went to bed and rolled, tossed, and jingled right along, the same as ever…”

One of the most interesting questions for researchers is what distinguishes an earworm that torments the sufferer and an earworm that is experienced as pleasant (nearly all of mine are of the latter type.) It seems to depend on personality and “musicality,” and even on how much one listens to and engages with music. An earworm well known in popular culture, and possibly responsible for widespread hatred of the late Walt Disney, is “It’s A Small World,” played relentlessly during the theme park ride:

WARNING: DO NOT CLICK ON THIS VIDEO UNLESS YOU WANT AN EARWORM THAT COULD LAST FOR YEARS!!

I leave it to readers to decide how much more they want to read about the science of earworms. I hope the above reviews and papers will be helpful. But as I write about my own earworms in the coming weeks and months, I will be stressing not so much their cognitive features as their meanings, for me and for others—a phenomenological approach, if you will. Thus one of my favorite papers from my literature review was published last year in Music Perception, by three researchers at the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia. It’s amusing title—”Singing in the Brain”—reflects the team’s conclusion that “an earworm results from an unconscious desire to sing along to a familiar song.”

That conclusion is consistent with other research showing that earworms tend to capture fragments of songs or tunes for which we do not know all the lyrics and are trying to remember them. This certainly conforms to my own experience: I would love to be able to sing an entire song in my imagination, maybe even concoct an auditory hallucination of me performing it in a concert hall Springsteen-style and have Courteney Cox come join me to dance on stage. But to be a wannabe imaginary rock star you have to know the words!

To me, at least, an earworm is not something to fight or resist, but to give in to, enjoy, and explore the meaning of—as I did with “September in the Rain” after my mother died, and as I have been doing for weeks with “These Days” by Jackson Browne (and other examples I will discuss.)

Join me next week (probably) for that next installment. And in the meantime, please do not hesitate to weigh in with your own experiences in the Comments section below.

I love that song, "These Days" - especially the Kate Wolf version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3T-uZ2osgdc