A "Critical Review" of Covid-19 Origins Leaves Out Some Critical Questions [With important updates]

A preprint paper authored by 21 scientists relies heavily on assurances by Chinese scientists and officials, and neglects to mention possible conflicts of interest by its lead author.

As the debate over the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to rage, it is becoming increasingly clear how strongly some participants are invested in a particular explanation, either the natural origins hypothesis or the lab-leak hypothesis (there are other ideas, but these are the two main contenders.)

As I have stated previously, I personally have no opinion, for the simple reason that I don’t believe there is enough evidence to come to any firm conclusions. Most scientists and science journalists acknowledge that when they give at least lip service to the need to investigate the origins question fully, which has not yet been done—not even close.

Nevertheless, we are still being treated to the spectacle of both scientists and science journalists publicly lobbying for one or the other side of the debate. My own observational conclusions are that the natural origins side is lobbying harder for its position; those who think a lab-leak (eg out of the Wuhan Institute of Virology) is possible or even likely still seem to acknowledge that the natural origins explanation is plausible. But many natural origins advocates don’t seem to want to return the favor.

As I wrote earlier, I got involved directly in this issue as a commenter (one with extensive scientific and science journalism experience) when one of our leading science writers, a friend and colleague at the New York Times, Tweeted that the lab-leak theory was racist. That really shocking violation of journalistic standards was quite an embarrassment to many science writers, and the colleague in question soon deleted it.

But similar, although perhaps more subtly phrased, comments have been made on social media by other science journalists and scientists, which has led me to think that something is going very wrong with the discussion.

The latest example is a preprint posted earlier this week on Zenodo by a group of 21 scientists, entitled “The Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Critical Review.” There is no question that the 21 are qualified to opine on the subject, as most of them are virologists or members of scientific fields relevant to the study of pandemics such as Covid-19. But as I will discuss below, the review is hardly an objective and dispassionate analysis of the existing data. Rather, like many things that scientists are publishing on this subject right now, the paper takes a clear point of view—against the lab-leak hypothesis—and not only selectively marshals evidence for that position, but leaves out some important information that would allow readers to evaluate the objectivity of the authors.

Why did Edward C. Holmes not reveal his association with China’s CDC?

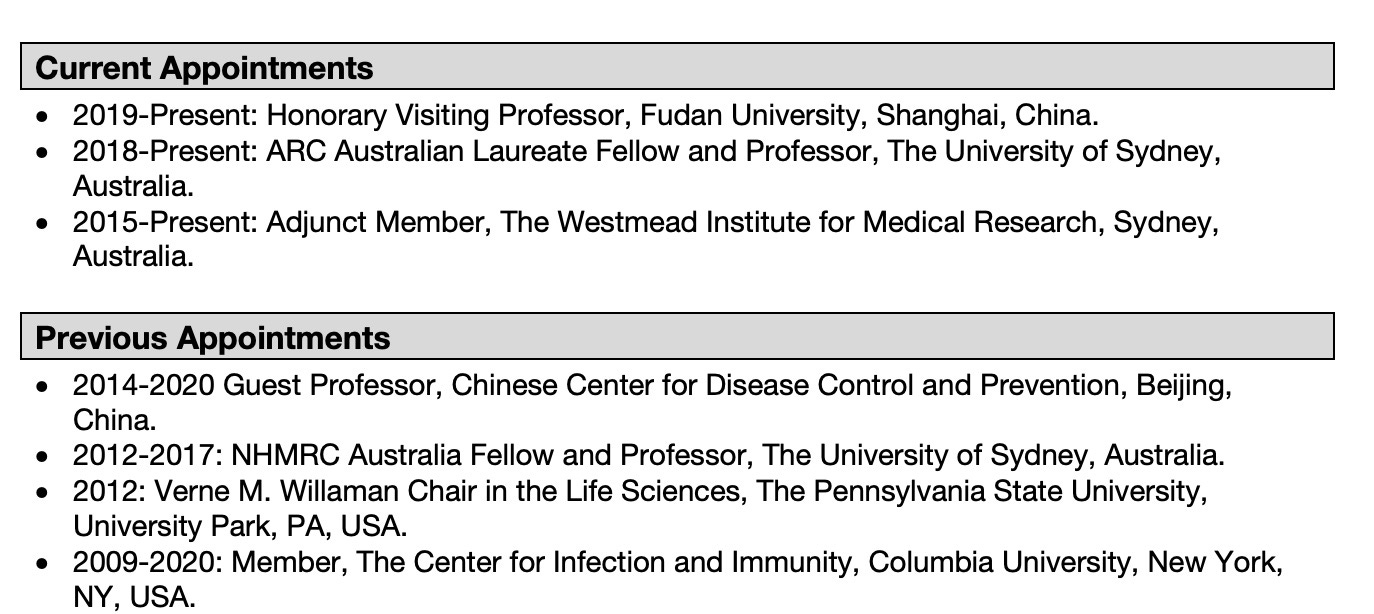

Edward C. Holmes is an evolutionary biologist and virologist at the University of Sydney in Australia, first author of the “Critical Review,” and a close collaborator with Chinese scientists going back a number of years (his CV lists 26 papers he has published in collaboration with Chinese scientists and institutions). Holmes is also a Guest Professor at the Chinese CDC in Beijing, from 2014 to the present, and an Honorary Visiting Professor at Fudan University in Shanghai. He worked closely with Chinese scientists at the very beginning of the pandemic, including on the sequencing of the virus’s genome.

(I want to acknowledge science journalist Paul Thacker for raising the fact earlier that Holmes did not acknowledge these potential conflicts of interest in the new paper.)

But in the acknowledgements for the Critical Review, where all the authors listed possible conflicts of interest, Holmes (ECH) identified himself as follows:

This is not to say that we do not want scientists outside of China collaborating with those inside China, far from it. But given the clear evidence that Chinese officials have withheld critical information relevant to deciphering the origins of Covid-19—including from a WHO team that visited the country early this year to investigate just that issue—it is clearly incumbent on researchers to disclose such ties. If that were not true before, it most certainly is now that the conflicts of interest of Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance who not only worked with and helped to fund Chinese scientists but also surreptitiously organized a letter in The Lancet denouncing the lab-leak hypothesis as a “conspiracy theory”—have been exposed.

(It is unfortunate that it took Freedom of Information Act requests by advocacy groups to reveal some of Daszak’s conflicts; that is something the mainstream media could have and should have done.)

Holmes’s defense of the Wuhan lab against allegations that it might have been responsible for a release of the virus began early in the pandemic, and has not abated since. I have written to Holmes to ask why he did not reveal his China connection in the acknowledgements, and will update this post if he responds.

A brief critique of the “Critical Review”

I just want to say a few things about this paper, because I think those interested should read it themselves and consider its logical fallacies very carefully.

The main problem, in my view, is that the authors are clearly out to muster as much “evidence” as they can for the natural origins hypothesis. But what they muster is not really evidence at all: It is suppositions about how what happened in past pandemics might inform our understanding of the current Covid-19 pandemic, and suppositions about what the genome sequence of the virus says about its origins. Certainly it is interesting and relevant, as the authors write, that past infections of humans by coronaviruses have been largely the result of so-called zoonotic transmission between animals and humans. And it is not unreasonable to think that the earliest widespread human infections could have occurred in the Wuhan seafood market, as the authors suggest, even if there is no clear evidence that this is where they began.

All of this is consistent with the natural origins hypothesis, although it does not prove it or even provide actual evidence for it—correlation, as scientists are fond of saying, is not causation (or confirmation.)

Likewise, the authors’ argument that the genetic properties (genome sequences) of SARS-CoV-2 are consistent with a natural origin is, again, not based on actual evidence but certain assumptions—assumptions which other scientists have pointed out a number of times are potentially faulty. Thus the authors assume, as have many others arguing against the lab-leak hypothesis, that a lab-leak scenario requires that the virus was “engineered” in some way, that is genetically modified, perhaps in what are called “gain of function” experiments designed to enhance the infectivity or transmissibility of the virus in the well-intentioned effort to study how to block infection of humans.

But a number of scientists have pointed out that such “engineering” would not be necessary for a lab-leak to have occurred. Thus the virus that causes Covid-19 could have been recently or previously collected by the Wuhan lab, which collected coronaviruses from all over China, including ones known to have infected humans and made them sick. The fact that the best known of these viruses, from a mine far from Wuhan and which made some miners sick—a virus now known as RaTG13—was probably not the culprit does not mean that another virus, which itself might have escaped from the lab, could not have been.

In a writeup about the Critical Review in the New York Times by my friends Carl Zimmer and James Gorman, Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers who is quoted often in the debate, points out that arguing that an engineered virus is a requirement for the lab-leak theory is a “straw man.”

“Dr. Ebright said it was possible that a W.I.V. lab worker might have contracted the coronavirus on a field expedition to study bats or while processing a virus at the lab. The new paper, he argued, failed to address such possibilities.”

The Times article also quotes David Relman, a microbiologist at Stanford University who along with others has called for a serious investigation of Covid origins:

“Basically, it really boils down to an argument that because nearly all previous pandemics were of natural origin, this one must be as well,” said David Relman, a microbiologist at Stanford University who organized the May letter to Science.

He noted that he does not object to the natural origin hypothesis as a plausible explanation for the pandemic origin. But Dr. Relman thinks the new paper presented “a selective sampling of findings to argue one side.”

But to me the worst fault of the Critical Review is its unquestioning reliance on what Chinese officials and scientists have been willing to say, or not say, about the pandemic. Here are some examples:

Referring to coronaviruses with sequences closer to SARS-CoV-2 than RaTG13:

“None of these viruses were collected by the [Wuhan Institute of Virology.]”

Re the origins of the virus:

“…there is no data to suggest that the WIV—or any other laboratory—were working on SARS-CoV-2, or any virus close enough to be the progenitor, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Re work at WIV:

“No published work indicates that other methods, including the generations of novel reverse genetics systems, were used at WIV to propagate infections SARS-CoVs based on sequence data from bats.” [Italics added]

Conclusion:

“There is no evidence that any early cases had any connection to the WIV…nor evidence that the WIV possessed or worked on a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 prior to the pandemic.”

As scientists also like to say, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. All of these statements rely heavily, or exclusively, on representations that Chinese scientists and officials have made and which none of the 21 scientists who signed this paper have any direct way of knowing are true. (None of the authors are based in China. One thing we do know, Chinese officials were trying hard to cover up the outbreak in Wuhan from the very beginning—indeed, in January 2020, journalists were pretty much able to track the coverup in real time.)

That doesn’t mean they are not true, or could not be true. Perhaps they are. But they do not constitute evidence—rather, they suggest the lack of it. Again, just to stress the point, there is no question that from the beginning of the pandemic Chinese officials sought to suppress information and data that many scientists say they need to fully investigate what happened. There are even some strange, still unexplained events—such as the deletion of viral sequences from a key database—that require some serious explanation.

I hope the debate over the origins of Covid-19 can somehow straighten itself out, divest itself of (fairly obvious) biases, and show the public the responsible side of both science and science journalism. And indeed, many involved in the controversy have been careful not to draw conclusions when there is so little evidence to base them on. They are setting the example for how we most move forward if we ever really want to know what caused a pandemic that has killed 4 million people around the world.

Update July 10: After science journalist Paul Thacker Tweeted about Edward Holmes’s role at the Chinese CDC earlier today, Holmes changed his CV to reflect that he supposedly ended that role last year (the previous version indicated that it was ongoing.) Below is a partial screenshot of the new CV. Also, as Thacker points out, Holmes was a coauthor on a March 2020 paper that is often cited as evidence against the lab-leak hypothesis, by Kristian Andersen et al. in Nature Medicine. In that paper also, Holmes did not disclose his ties to Chinese scientific institutions and colleagues.

Update July 12: Alina Chan of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, MA, a major player in the Covid-19 origins debate, has just published her own response to the Holmes et al. “Critical Review.”