Don’t bet money on the market spillover hypothesis for Covid-19 origins. Bayesian analysis concludes the odds are heavy you will lose. [Updated]

Circumstantial evidence that the Wuhan connection is not just a coincidence continues to mount. And a new Bayesian analysis puts the odds of a market spillover at no better than one in about 30.

When the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in the Chinese city of Wuhan, a lot of eyebrows were raised—and not just among scientists. Wuhan, as many knew, was the home of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), which had gained fame after the SARS outbreaks of 2002-2004. Researchers in Wuhan, including virologist Shi Zhengli—who would become internationally known as the “Bat Woman” for her forays into bat caves in southwestern China—had established Wuhan as a world center for coronavirus research.

While the general public probably had only a dim inkling of what kind of research went on at the WIV, experts in the field knew that it included years of creating chimeric SARS-like viruses, mixing and matching segments of viral genomes to see what mutations would make them more infectious to humans. Much of this work had been done in collaboration with scientists in the United States, Australia, and other countries. And while the goal of the work was supposedly to help prevent a pandemic of the kind that SARS had threatened to become twenty years ago, some scientists—including WIV collaborator Ralph Baric at the University of North Carolina—had begun warning of the potential risks of this so-called “gain-of-function” a number of years ago.

Indeed, their knowledge of what kinds of research was going on at WIV would lead a group of scientists to alert Anthony Fauci about a possible lab origin for the emerging pandemic as early as January 2020. While this same group would go on to author the infamous “Proximal Origin” letter in Nature Medicine just a few months later, arguing that a lab origin was “not plausible,” they privately continued to tell each other just the opposite—as recently revealed by documents subpoenaed by Congressional investigators.

But while many scientists, along with science journalists who dutifully repeated what they said, tried early on to put the kibosh on any suspicions that the pandemic virus SARS-CoV-2 had emerged from a lab or other research-related activity, other researchers and many members of the public refused to believe that the so-called “lab leak” hypothesis was just a “conspiracy theory.” One big reason is what might be called good old common sense: It seemed just too much of a coincidence that the pandemic began right there in the city with the world’s most famous coronavirus lab, which was actively studying exactly the group of coronaviruses responsible for Covid-19 (the so-called SARS-like viruses, belonging to the subgenus Sarbecovirus.)

Of course “common sense” is not science. So when numerous researchers favorable to the zoonotic spillover hypothesis began to tell us the Wuhan connection was just a “coincidence,” that seemed authoritative, especially to science journalists whose job it was to try to make sense of it all. The odd thing, however (excuse the pun) is that the term “coincidence” is not scientific either. As normally used, it denotes a guess about what the odds of any particular event might be, but does not include a calculation of those odds using any accepted mathematical approach.

And when other scientists attempted to do those kinds of calculations, they kept coming up with an uncomfortable answer: The odds of the pandemic arising in Wuhan naturally, taking in all of the factors we know about, were actually pretty low. One such early attempt, performed by a scientist and biotech entrepreneur named Steven Quay, concluded as follows:

“The outcome of this report is the conclusion that the probability of a laboratory origin for CoV-2 is 99.8% with a corresponding probability of a zoonotic origin of 0.2%.”

Another early Bayesian analysis, performed by Gilles Demaneuf (of DRASTIC fame) and Rodolphe De Maistre, came to similar although not quite as drastic conclusions.

Those outcomes do not look good for the zoonotic origin hypothesis. But are they valid?

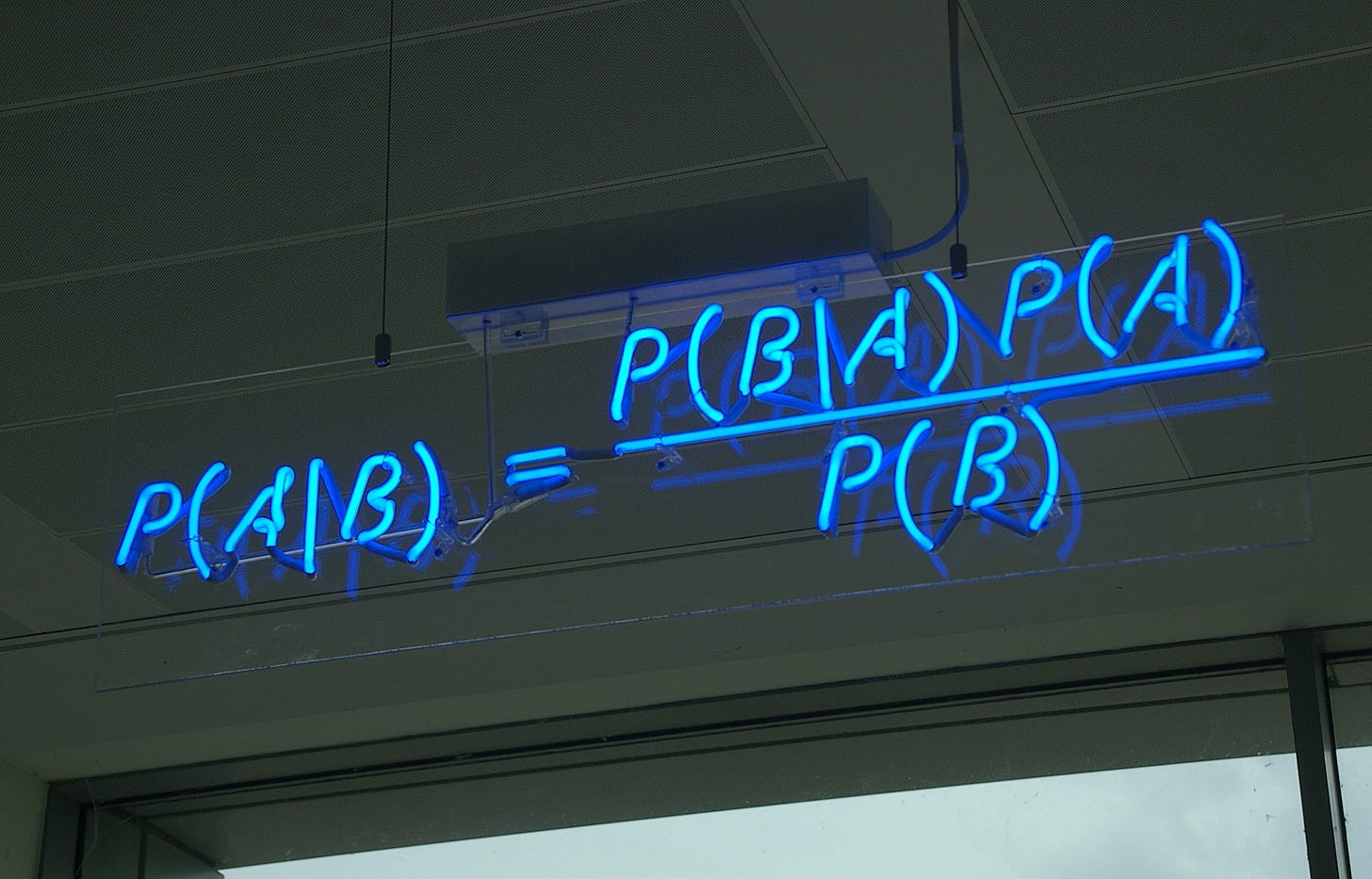

At this point we need to meet the man in the drawing at the top of this post, Thomas Bayes. Or, at least, the man the drawing is claimed to depict. According to Wikipedia we don’t have any confirmed representations of Bayes, an 18th century English statistician, philosopher, and Presbyterian minister. What we do have, however, is Bayes’ powerful theorem, an established method for calculating the odds of any particular outcome by factoring in the events that are credibly related to that outcome. It is widely used in science—although apparently many scientists don’t know how to use it and leave that to the statisticians on their research teams—and very well suited to figuring out questions such as the likelihood of any particular hypothesis.

I won’t try to explain the theorem in detail here, because just a bit of Googling will lead you to good online explanations including some very cool YouTube videos showing how it works. And without realizing it, many of us use a simple version of the theorem every day in our thinking about human events.

In fact, when someone thinks, “Gosh, it seems like a pretty big coincidence that the pandemic started in the city that has the world’s most famous bat coronavirus lab,” they are doing an informal version of Bayes analysis. If they then add in other uncontested, known factors—eg, the published work showing WIV scientists were creating chimeric SARS-like viruses; the documentation that the WIV together with scientists in the U.S. and Singapore submitted a grant proposal describing work that would include inserting infection-enhancing furin cleavage sites into SARS-like viruses; the known fact that of all the 200 or so Sarbecoviruses so far identified, only SARS-CoV-2 has a furin cleavage site—they are doing Bayes analysis in their heads, although obviously not in a rigorous fashion using formulas and computers.

Last month, Michael Weissman, a retired physics professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, published on Substack what many Covid origins watchers consider the most detailed and convincing Bayes analysis of the question. (I am linking to Weissman’s revised September 10 version, but he provides a link to the original version published on August 31 for reference and full disclosure. Weissman also tells me that a newer version of his post, including some corrections that do not affect the result, will be posted soon.)

Unlike Steven Quay, who put the odds of a zoonotic spillover at only 0.2%, Weissman’s conclusions were more generous to the market hypothesis, which still lost out heavily: A likelihood of about 70 to 1 in favor of a lab origin, and probably no less than 28 to 1. (This is also roughly consistent with a Bayesian analyses performed by scientist Alex Washburne, a major contributor to mathematical approaches to Covid origins theorizing.)

[Update: A few hours after this was posted, Weissman issued a revised analysis that took into account the 2019 timing of the pandemic. The new calculations raise the odds in favor of a lab origin to 90 to 1, with the lower limit unchanged.]

Weissman is an interesting guy in his own right. He was an active duty physics prof at UIUC from 1978-2009, and continues his research as emeritus, largely on condensed matter physics. He is also a political activist: He spent time in jail in 1971 for draft card mutilation, and in the mid 1980s was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Barbara Boxer and others for for starting a scientific boycott of Reagans Star Wars project. Weissman has also recently focused on, as he put it to me, “showing that a lot of published work in physics education research is seriously wrong even at the level of freshman stats.”

I hope you will read Weissman’s analysis carefully, but let’s at least hit the highlights here. Key to a legitimate Bayesian analysis is entering only data and factors that we can be sure about. So we don’t put in unconfirmed allegations by a CIA whistleblower that the agency paid off analysts to favor a market origin, or unconfirmed allegations that three WIV lab workers got sick from a viral infection in fall 2019—much as we might hope to eventually confirm or falsify such contentions. We stick to the facts.

Late in the study, Weissman provides a detailed table of the factors he included in the analysis, but with his indulgence let me reproduce that here. Note that Weissman does not use data or analyses that are problematic for various reasons.

[Note: In Weissman’s revised analysis, posted today, he adds the factor of the 2019 to this chart.]

Note that Weissman does not use certain factors that some lab leak enthusiasts consider highly supportive of their conclusions—such as the presence of a furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2—nor does he include the widely cited pro-zoonosis conclusions of Worobey et al. published in Science last year, in both cases because there are alternative conclusions consistent with both competing hypotheses. This conservative approach avoids falling into speculative traps.

It’s interesting to see Weissman’s explanation for why he does not include the furin cleavage site in the analyses, a feature of SARS-CoV-2 that many “lab leakers” consider a smoking gun. His reasoning demonstrates the strength of the Bayesian method, which results in conclusions that are very conservative.

“Some LL advocates have argued that the mere fact that SC2 has an FCS is strong evidence for LL since no close relative of SC2 has an FCS and DEFUSE proposed adding an FCS. As we have seen, even the lead author of Proximal Origins thought the FCS was at least some evidence favoring LL. Nevertheless, the argument that having an FCS gives a major factor is exaggerated, since it would only apply to some generic randomly picked relative. SC2 is not randomly picked. We are only discussing SC2 because it caused a pandemic. So far as we know having an FCS may be common in the subset of hypothetical related viruses that are capable of causing a pandemic. In other words P(FCS|ZW, pandemic) may be nearly 1 even though P(FCS|ZW) is much less than 1 for some generic sarbecovirus. Therefore I will not use the mere existence of an FCS to update the odds.”

Despite this rigororous and cautious approach, in some ways the factors that go into a detailed Bayesian analysis are still similar to those that go into a “common sense,” seat of the pants evaluation of the odds, at least—and here I am editorializing—if it is done by honest people. On the other hand, the furin cleavage site argument is an example of how common sense could lead us astray (I must admit that I have long considered it pretty close to a smoking gun myself.)

Whether this all means that common sense is Bayesian in nature, or Bayesian analysis is just common sense, or both, I cannot pretend to know (although it might be worth thinking about.) At any rate, we do know that about two-thirds of Americans surveyed in recent polls favor the lab origin hypotheis, and that might not be because they are stupid, ignorant, or Republicans.

In the latest version of his analysis, posted on this date of September 22, Weissman concludes that the odds against the zoonotic spillover hypothesis are likely to be at least 90 to 1, and not likely to be less than 28 to one, depending on the assumptions made and the mathematical methods used. Even assuming errors in those assumptions, which Weissman discusses, the odds against zoonosis cannot be surmounted.

“The bottom line is just that [lab leak] looks at lot more probable than [zoonosis], with room for argument about exactly how much more probable.”

One thing about Bayesian analyses, they can always be improved based on new data. Weissman’s analysis is a work in progress. As he writes in the introduction to the very latest version of his study:

“[This version is substantially changed based on: (1) my realizing I’d forgotten to use coincidence in timing, analogous to coincidence in location; (2) A wonderful twitter exchange with pseudonymous users making me aware that codon usage in long insertions is substantially different from that in the overall genome. It’s awkward to make such big adjustments after posting an initial version, but this is an unusual area where the normal lively open pre-publication scientific conversations are almost impossible to find. The one sentence that has been in italic boldface from the start is unchanged. The method is explicitly ready for correction based on improved reasoning or new evidence.]”

If a lab origin for Covid-19 is most likely, why aren’t they telling us that?

One often hears that “most scientists” favor the market hypothesis, or even that there is a “scientific consensus” around zoonosis. However, there is no basis for such statements. No one has conducted a survey of the entire scientific community on the subject, nor would such a survey likely be practical. Instead, journalists tend to quote a small number of researchers, mostly virologists, who early in the pandemic formed into a self-appointed corps of “experts” on the subject and often attack anyone who disagrees with virulence, as it were.

The problem, as I think most recognize, is that the origins question has become hopelessly politicized, and it is sometimes very difficult to get beyond the “Republicans are for lab leak, Democrats are for zoonosis” formulation. I say hopelessly, although that might be changing. Just over the past few weeks, a number of developments suggest that the lab origin hypothesis is becoming increasingly plausible, even in the eyes of scientists.

— A few days ago, the Department of Health and Human Services debarred the Wuhan Institute of Virology from receiving NIH funds for 10 years. The main reason was the WIV’s refusal to report what it had done with the money it already received from NIH to perform what is now documented as gain-of-function research.

As HHS put it in a September 19, 2023 letter to the WIV: “WIV conducted an experiment that violated the terms of the grant regarding viral activity, which possibly did lead or could lead to health issues or other unacceptable outcomes.”

While HHS has zeroed in on one particular experiment it deemed to be particularly dangerous gain-of-function research, this is the closest the U.S. government has ever come to acknowledging that research at the institute might have led to the pandemic.

— Earlier this month, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) shut down a $125 million virus hunting program, the followup to the $200 million PREDICT program USAID had sponsored over about a decade. PREDICT, which supported the WIV and other institutions in what some scientists consider risky virus research, obviously failed to “predict” the Covid-19 pandemic. The apparent reasons for terminating the new program is that the funded research was deemed too risky itself.

— Congressional investigators have talked to a whistleblower in the C.I.A. who told them that a senior analyst bribed a half dozen analysts to change their evaluations from favoring lab origin to favoring zoonosis. While this obviously needs to be confirmed—and in some ways is difficult to believe as stated—it is the case that both the FBI and the Department of Energy lean towards a lab origin explanation for the pandemic.

— An analysis by virologist Jesse Bloom of the Fred Hutchinson cancer research center in Seattle, which strongly questioned claims that raccoon dogs were the intermediate host between bats and humans, has now been published in a peer reviewed journal. Previously, a group of scientists, aided by a few credulous reporters, had claimed that this was the “strongest evidence yet” for zoonosis. This misleading story rocketed around the world’s media, and still has not been corrected by most media outlets—including, unfortunately, the top journal Science, which has failed to report on Bloom’s work (the New York Times, to its credit, has done so.)

Yet while the lab origin hypothesis may be the most likely explanation for the pandemic by far, and even obvious in the minds of many, it has yet to be formally proven. That will require either more whistleblowers, a coming clean by Chinese authorities who have refused to share early data despite pleas by the World Health Organization and funding cuts by NIH, some hard evidence that perhaps the intel agencies already possess, or other scientific or forensic evidence. One thing is sure: The debate will not end until or unless we know the truth, no matter how much some want to convince us they already know the answers.

I will let Weissman have the last, Bayes-inspired word on these questions, where P is the probability, LL is lab leak, and ZW the most likely version of zoonosis:

“How then could so many serious scientists have concluded that P(ZW) is bigger than P(LL) or even that P(ZW) is much bigger than P(LL)? There was of course a great deal of intensely motivated reasoning, as the recently published internal communications among key players vividly illustrate. For those just following the literature in the usual way, the impression left by the titles and abstracts of major publications suggested that ZW had been confirmed, although we’ve seen that the arguments in the key publications disintegrate or even reverse under scrutiny.”

For extra credit:

The way that the zoonotic spillover hypothesis has become favored by many scientists is not just a matter of political bias, but also due to a chronic error in how science is done that a number of commenters have written about lately. Weissman refers to that problem in one passage that readers might study carefully, including the link to a Nature commentary on the use of p-values. As I often comment, based on 40+ years as a scientifically trained science journalist, scientists are not necessarily scientific in their thinking just because they have PhDs or even lots of experience in their research fields.

“There has also been a familiar methodology problem among the larger community that accepted the conventional conclusion. Although simple Bayesian reasoning is often taught in beginning statistics classes, many scientists have never used it and fall back on dichotomous verbal reasoning. The initially more probable story, ZW in this case, is given qualitatively favored status as the “null hypothesis”. Each individual piece of evidence is then tested to see if it provides very strong evidence against the null. If the evidence fails to meet some high threshold, then the null is not rejected. It is a common error to then think that the null has been confirmed, rather than that its probability has been reduced by the new evidence. After a few rounds of this categorical reasoning, one can think that the null has been repeatedly confirmed rather than that an overwhelming likelihood ratio favoring the opposite conclusion has been found.”

Another way of stating this is that the threshold for any new evidence that might contradict the zoonosis hypothesis is kept so high, and that evidence dismissed so deliberately and readily, that instead of scientific argument we have special pleading. In other contexts, special pleading is widely recognized as intellectually dishonest.

Thank you for alerting me to Michael's analysis and its clear introduction here. I'll be sharing both in my weekly news review tomorrow.

I'm just amazed at the tweet by the editor of Scientific American. HOW could she have written that, and MONTHS after two magisterial pieces of reporting, in Boston Magazine and New York, on the entirely plausible possibility of a lab leak (and maybe Nicholas Wade was already reporting on it, too?) Was it sheer laziness on her part? Stupidity? Intellectual dishonesty? Has she ever recanted?