More bad journalism from the New York Times. It's Covid origins, again (an exegesis)

A long-awaited piece by science writer David Quammen starts off fair enough, but quickly degenerates into a misleading and biased article that leaves out lots of key facts.

On July 25, the New York Times Magazine published a lengthy and long-awaited article by science writer David Quammen, entitled “The Ongoing Mystery of Covid’s Origin.” I say “long-awaited” because Quammen has dropped many broad hints over the past months that it was coming. I don’t envy Quammen the task: During the time he was preparing it, a lot of things happened in the fierce Covid origins debate, ranging from raccoon dog studies to intel reports to media leaks to Congressional hearings.

Most recently, claims that an early and key scientific letter in Nature Medicine dismissing the plausibility of a lab origin for the pandemic virus were fraudulent have erupted, leading to a petition demanding that the so-called “Proximal Origin” paper be retracted. (I wrote about these events recently for this newsletter.)

Quammen’s article was also long-awaited, however, because proponents of a lab or research related origin for Covid-19 fully expected that the article would be biased, as with Quammen’s previous writings on the subject, towards the competing zoonosis or zoonotic-spillover hypothesis. Indeed, in Quammen’s book “Breathless,” much of which covered the origins question, that bias was explicit; I commented on the problems with the book in several Twitter threads.

Other recent evidence of Quammen’s perspective—what, in the Times Magazine piece he calls “priors”—came in a recent opinion piece in the Washington Post about the current Congressional investigation into Covid origins, entitled “Lets leave the Covid origin mystery to scientists.” In that piece, Quammen stated his conclusion quite clearly: “The lab-leak idea stands as a long-shot alternative to the far stronger hypothesis of a natural origin.”

Morever, he characterized so called “lab leakers” (as opposed to the “zoo crew” or “zoonati”) as follows: “Other opinionizers on the covid-19 origin question, mostly amateur sleuths but also some journalists, have argued since early 2020 that this coronavirus came to humans — maybe? probably? definitely? — from a laboratory.”

Much as I hate to reveal my own “priors” so early in this piece, this statement is simply false. In fact, hundreds of bona fide scientists with PhDs and other academic degrees either lean towards a lab origin or are convinced that is the solution to Quammen’s “mystery.” Many are vocal on social media, others express their views more privately, but they are certainly out there.

Nevertheless, when I saw the subhead of Quammen’s new piece, I thought perhaps this time around he would provide a more balanced and accurate account:

We still don’t know how the pandemic started. Here's what we do know — and why it matters.”

And in fact, as I will discuss, the first half of the piece is fairly balanced, with a few quibbles I will mention. But as he moves methodically towards his foregone conclusion—no surprise, the evidence favors a natural origin, he maintains—the errors of commission and omission pile up so quickly that it’s hard to believe he did not know he was cherry-picking evidence in an increasingly dishonest manner. (I believe that in part because I and others had repeatedly pointed out the errors in his previous writings.)

In short, this article is a piece of bait-and-switch, in which Quammen—and his editors at the Times, who obviously are also responsible—tries to lull readers into thinking they are getting the best wisdom and reporting from a star science writer, only to be led down the garden path into a thicket of gaslighting and falsehoods.

That’s a strong statement, so I want to be clear about my qualifications to make it, and to put forth this exegesis of Quammen’s text (and also this exercise in media criticism, not always easy to do.)

I am a bit less than a year older than Quammen. We both started our journalism careers around the same time—me in 1978, and Quammen a few years later, according to his Wikipedia biography. Quammen did graduate work in literature at Oxford, and for a while tried his hand at fiction. He was a not-too-successful novelist at first, but then in 1981 turned to nonfiction, writing celebrated columns for Outside magazine. He went on to write 18 books, including “Spillover” and “Breathless,” along with quite a few magazine articles over the years.

As for me, having earned an MA in biology from UCLA in the late 1970s, I began a career as a freelance reporter in Los Angeles, focusing on everything from public health to AIDS to political reporting for the Los Angeles Times, L.A. Weekly, and Los Angeles magazine. In 1988 I moved to Paris, where I wrote about science and travel for the International Herald Tribune and many other publications; in 1991 I began my 25-year career as the Paris correspondent for Science. For the first decade of that gig, I was the European AIDS correspondent, serving as backup for Science’s primary AIDS reporter, Jon Cohen.

I have only written one book, but during my years at Science I wrote more than 900 articles, along with freelance pieces for Smithsonian, Discover, National Geographic, Scientific American, Audubon, and others.

Now, let’s get to it.

The bait before the switch.

I realize that not everyone reading this will have access to the New York Times Magazine. I will thus quote liberally out of Quammen’s piece, but of course I don’t expect you to trust me that I am not taking things out of context. Here is the link again. If you really want to check my work, I hope you will find some way to read the original article.

I said above that the piece started off with a reasonable approach, although I had some quibbles. But sometimes quibbles are important, so I want to mention a few.

Here is the long opening paragraph, what we in the business call the “lede.”

“Where did it come from? More than three years into the pandemic and untold millions of people dead, that question about the Covid-19 coronavirus remains controversial and fraught, with facts sparkling amid a tangle of analyses and hypotheticals like Christmas lights strung on a dark, thorny tree. One school of thought holds that the virus, known to science as SARS-CoV-2, spilled into humans from a nonhuman animal, probably in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a messy emporium in Wuhan, China, brimming with fish, meats and wildlife on sale as food. Another school argues that the virus was laboratory-engineered to infect humans and cause them harm — a bioweapon — and was possibly devised in a “shadow project” sponsored by the People’s Liberation Army of China. A third school, more moderate than the second but also implicating laboratory work, suggests that the virus got into its first human victim by way of an accident at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (W.I.V.), a research complex on the eastern side of the city, maybe after well-meaning but reckless genetic manipulation that made it more dangerous to people.”

Quammen is a good writer, but that is not always a positive thing with this kind of story. The effect of his first sentences is to make us feel this is an unsolvable mystery, “with facts sparkling amid a tangle of analyses and hypotheticals like Christmas lights strung on a dark, thorny tree.” The impact of such phrasing is to make readers not intimately familiar with the origins arguments decide early on that they can’t possibly understand it all, and thus they are more likely to put themselves into the writer’s hands—after all, Quammen is a famous science writer and he can be trusted, yes?

But I see another problem with this first “graf,” which some diehard “lab leakers” might not agree with. Quammen lays out three hypotheses for Covid origins. The second, the “bioweapon” hypothesis, is actually not considered seriously by very many scientists, and in fact has the least evidence to support it. Some think that recent revelations that scientists from China’s Peoples’ Liberation Army were involved with work at some of the Wuhan labs—especially the Wuhan Institute of Virology—is some kind of smoking gun for this idea. But that makes too many assumptions about the PLA’s role. For one thing, as those who have studied the Chinese revolution and the country’s history know, the PLA is intimately integrated into all aspects of Chinese society, even when there are no military aspects. And second, it is just as likely that the military was interested in biodefense rather than making bioweapons—just as the U.S. military is.

But by including this as the second of three hypotheses, to which he seems here to be giving equal weight, Quammen—deliberately or not—introduces an unlikely scenario, and immediately follows by saying that the lab origin hypothesis is a “more moderate” version of it. Intentionally or not, Quammen is loading the dice.

Quammen proceeds to lay out some of the history of the debate in a fairly evenhanded manner, and eventually lights on very current events: The Congressional investigation. He writes:

“And then, on July 11, the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic, led by Representative Brad Wenstrup, an Ohio Republican, convened a hearing at which he and colleagues interrogated two scientists, Kristian Andersen and Robert Garry, about their authorship of an influential 2020 paper that appeared in the journal Nature Medicine. That paper was titled “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” The tenor of the hearing was foretold by its own announced title: “Investigating the Proximal Origin of a Cover-Up,” and the proceedings that day consisted of accusation and defense, without shedding any new light, let alone yielding certitude about the origin of the virus.”

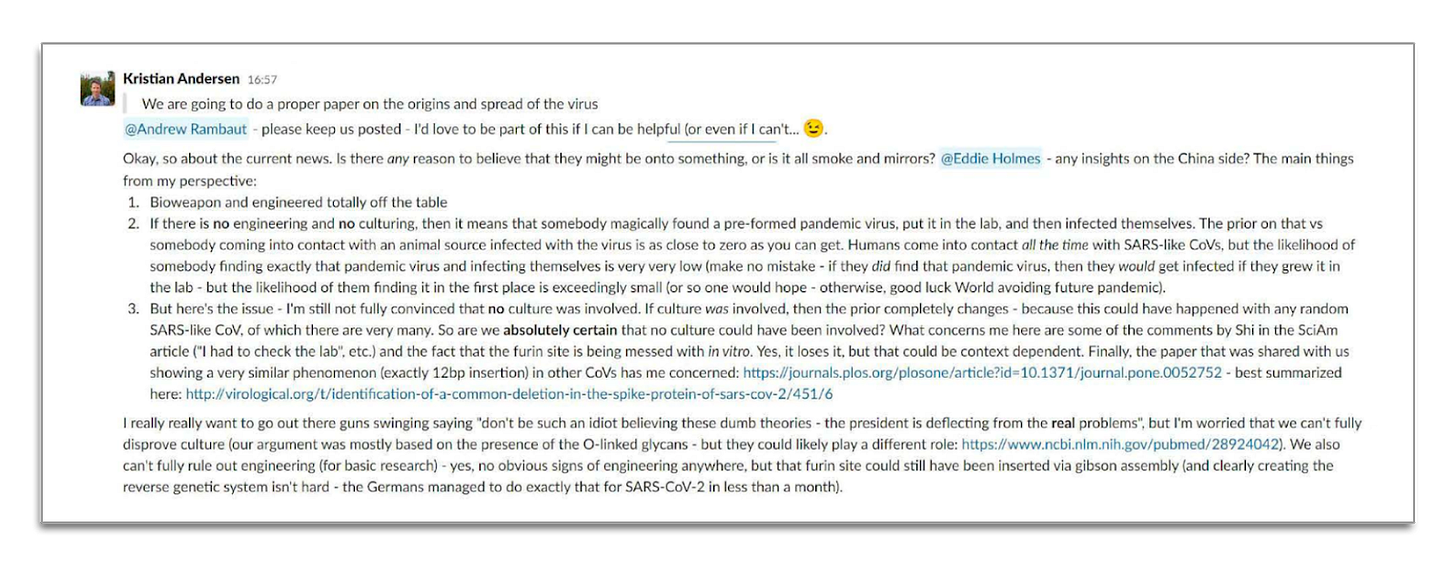

Later in the story, Quammen does refer to the emails and Slack messages released by the Subcommittee, written by the Proximal Origin authors, which reflect the “process” by which Andersen and the others supposedly changed their minds from suspecting a lab origin to concluding that was not at all plausible. But nowhere in the article does Quammen show readers the voluminous evidence that some of them—especially Andersen—continued to consider a lab origin possible long after the Proximal Origin letter was published (see the Public article linked to just above, my own post on this subject, and this Slack exchange from a month after Proximal Origin was published—with apologies for the poor visibility.)

In other words, despite all of their public statements, Andersen and his colleagues never changed their minds from their original opinion that a lab origin was very plausible. That, again, is why some scientists think they engaged in fraud—likely grounds for retraction.

What are your “priors?”

Quammen then engages in an interesting discussion with a couple of scientists, including virologist Jesse Bloom of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, about how prior assumptions can influence the way one looks at evidence—which is certainly true. (Bloom will become important again later in this post.)

Quammen decides to explore his own priors. Here he goes:

“That gave me pause to consider my own priors. For the past 40 years, I’ve written nonfiction about the natural world and the sciences that study it, especially ecology and evolutionary biology. During the first half of that, my attention went mainly to large, visible creatures like bears, crocodiles and bumblebees and to wild places like the Amazon jungle and the Sonoran Desert. I came to the subject of emerging viruses in 1999, during a National Geographic assignment, when I walked for 10 days through Ebola-virus habitat in a Central African forest. Later I spent five years writing a book about zoonotic diseases and the agents that cause them, including the SARS virus, the earlier killer coronavirus now often called SARS-CoV-1, which emerged in 2002 and spread in human travelers from Hong Kong to Singapore, Toronto and elsewhere, alarming experts deeply. Scientists traced SARS-CoV-1 to palm civets, a type of catlike wild carnivore sold as food in some South China markets and restaurants. But the civets proved to be intermediate hosts, and its natural host was later identified as horseshoe bats.”

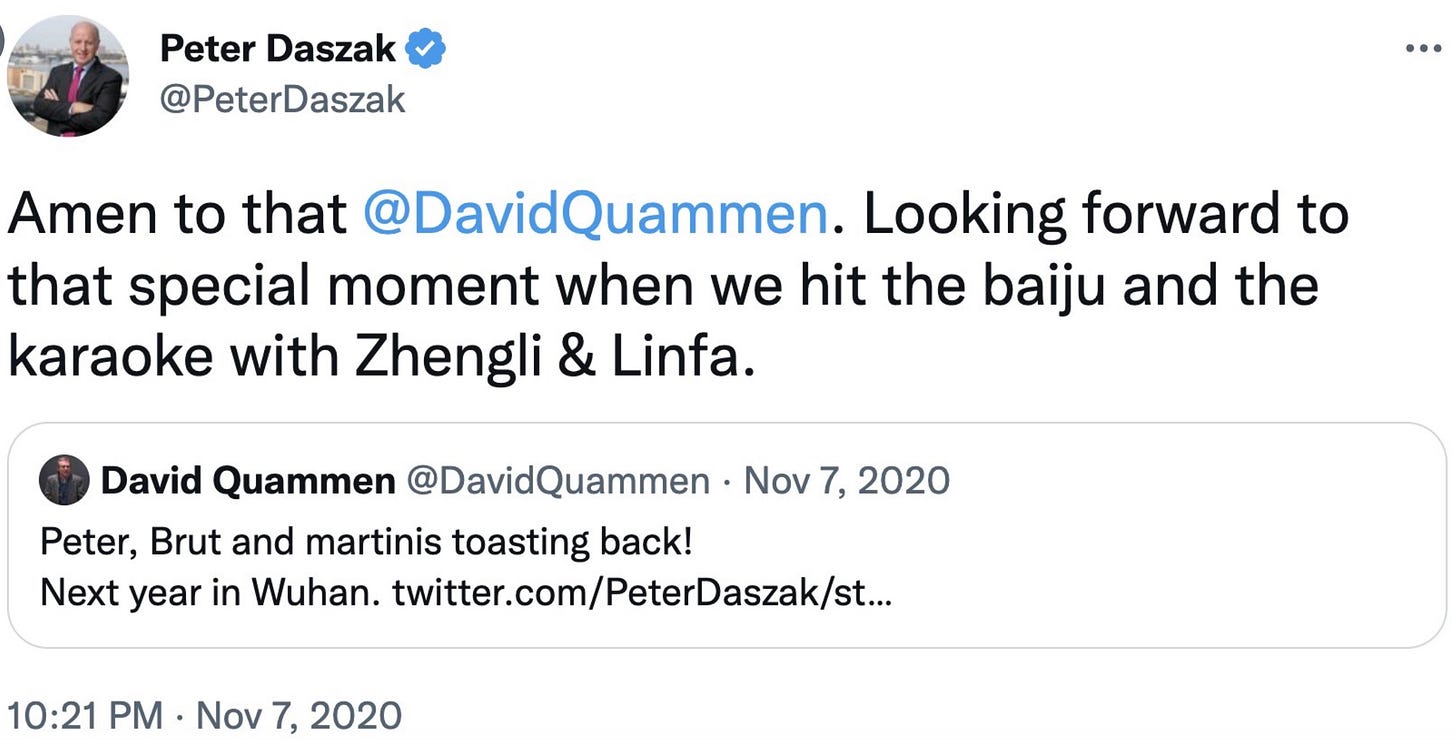

I’ve quoted this paragraph in full so as not to be suspected of selective quoting. But there is a problem: Quammen has not disclosed that he is good friends with some of the researchers most suspected of collaborating on the research that might have led to a lab accident: Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, which funneled NIH funds to the Wuhan Institute of Virology; Shi Zhengli, the WIV’s famous “Bat Woman;" and Linfa Wang, a scientist in Singapore and close collaborator with Shi.

Many, and I hope most, journalists and editors would agree that this kind of close association with major players in a story, whom Quammen got to know when he researched his book “Spillover,” should be disclosed. This is something the New York Times editors should have insisted on.

To Quammen’s credit, he does go on to acknowledge a critically important element in the Covid origins discussion: The frequency of lab accidents, which is not rare as some have tried to maintain. I will quote this paragraph without much comment, but it’s important: Does Quammen realize how credible this makes the lab origin scenario, and that it cannot be dismissed as a “conspiracy theory?” If so, that understanding does not carry on as the article continues.

“Research accidents have occurred, too, in the history of dangerous new viruses, and longtime concerns over such accidents constitute the priors of some who favor the lab-leak hypothesis for Covid. Such accidents might number in the hundreds or the thousands, depending on where you put the threshold of significance and how you define “accident.” There was an event that (probably) reintroduced a 1950s strain of influenza in 1977, causing that year’s flu pandemic, which killed many thousands of people, and a 2004 needle-stick injury of a careful scientist, Kelly Warfield, while she was doing Ebola research (but she proved uninfected by Ebola). Also in 2004, just a year after the global SARS scare, two workers at a virology lab in Beijing were independently infected with that virus, which spread to nine people in total, one of whom died. This followed two other single-case lab-accident infections with SARS virus the previous year, one in Singapore, one in Taiwan.”

Furin cleavage sites, raccoon dogs, and gaslighting.

A little more than a third of the way into the article, the saving graces of honest paragraphs like the one above begin to dissipate rapidly. Notable is Quammen’s first mention of the furin cleavage site, a molecular feature that allows SARS-CoV-2 to more readily infect humans. While other coronaviruses have it, no other member of the subgenus the pandemic virus belongs to—known as the Sarbecoviruses, of which about 220 are known—has this feature. This was a real eye opener to Andersen and his colleagues, as Quammen describes:

“Holmes, Andersen and their colleagues recognized the virus’s similarity to bat viruses but, with more study, saw a pair of ‘notable features’ that gave them pause. Those features, two short blips of genome, constituted a very small percentage of the whole, but with potentially high significance for the virus’s ability to grab and infect human cells. They were technical-sounding elements, familiar to virologists, that are now part of the Covid-origin vernacular: a furin cleavage site (FCS), as well as an unexpected receptor-binding domain (RBD). All viruses have RBDs, which help them attach to cells; an FCS is a feature that helps certain viruses get inside. The original SARS virus, which terrified scientists worldwide but caused only about 800 deaths, didn’t resemble the new coronavirus in either respect. How had SARS-CoV-2 come to take this form?”

I want to note carefully here that this is the first of a number of references to the furin cleavage site, which is seen by numerous scientists as a major piece of evidence that the virus was engineered. And a few paragraphs after this one, Quammen notes, as I have, that the FCS is not found in any other members of this subgenus.

I’m going to skip lightly over a long section on the virus called RaTG13, which was found in a mine far from Wuhan in 2013 and later sequenced by Shi Zhengli and her colleagues. Much has been made of the fact that this virus, while more than 96% similar to SARS-CoV-2, was still too distant to the latter to have either evolved directly into it or to have been the “progenitor” of a genetically engineered virus that went on to cause the pandemic. Quammen repeats the often-quoted insistence by zoonosis proponents that if Shi Zhengli had such a progenitor virus in her lab she would have published it or we would know about it in some other way.

As a number of scientists have pointed out, however, this is nonsense. For one thing, as biologist Alex Washburne recently said on Twitter—to paraphrase—every published genome sequence or virus was once an unpublished genome sequence or virus. So this is a fallacious assumption. To make matters worse, the WIV and Chinese officials have refused to divulge exactly what research they were doing and what viruses they had in the lab; as a result, they have had their NIH funding entirely cut off, as Quammen must know because it has been widely reported.

I am also skipping over a long section which heavily implies that the lab origin hypothesis is the domain of amateur sleuths and right-wing politicians, with just a few exceptions such as former Clinton administration aide Jamie Metzl. Again, this is false, and again, Quammen knows better. To make matters worse, Quammen very briefly mentions scientists such as Alina Chan of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, MA, who has been a major figure since early in the pandemic in flagging possible evidence for a lab origin. Quammen does not interview her, or ANY—ANY— other scientist on the lab origin side of the debate. (He does, however, describe the contributions of a number of journalists who have raised questions about the dominant narrative.)

Quammen’s discussion of the Worobey and Pekar papers published in Science last year, the best evidence produced so far for a zoonotic origin in Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Market, also leaves out the half dozen or so challenges to those findings, some of which—including a critique of the “two spillover” contention—have now been published. That’s not surprising, because other than me and I think British science writer Matt Ridley, no journalists have covered the important fact that these studies have been seriously questioned by other scientists.

There’s lots more here that could be discussed, but I want to close out this part of the exegesis with two “errors” of omission so glaring that I think they are likely to be deliberate.

The first has to do with the raccoon dog story, which erupted last spring. Quammen describes it as follows:

“The surge of opinion toward the lab-leak idea was interrupted in March, when Florence Débarre, a scientist working for France’s National Center for Scientific Research, discovered another body of interesting evidence, long missing but now found. This was genomic data — from the swab sampling of door surfaces and equipment and other items, including that pair of discarded gloves — gathered at the Huanan market in early 2020 but withheld since that time. The data were released, perhaps by mistake, and Débarre was alert enough to spot them and recognize what they were. A team of researchers, including Worobey, detected a pattern in the data: strong proximity between samples containing raccoon dog DNA and others containing SARS-CoV-2 fragments (and some samples that contained both), from stalls in the southwest corner of the market where wild animals had been sold as food. Malayan porcupine DNA and Amur hedgehog DNA were also found near the virus, but raccoon dogs were of special interest because of their proven susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2.

These findings didn’t establish that raccoon dogs had carried the virus into the market. But they added plausibility and detail to that scenario.”

I’m quoting this in full because Quammen fails to tell readers what happened next: Virologist Jesse Bloom, whom Quammen quotes higher in the story, posted an analysis of the raccoon dog data that found a negative correlation between the presence of raccoon dog DNA and the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This study was reported by a number of publications, including the New York Times itself (for my own take on it, see here.) In other words, the much hyped raccoon dog story quickly fell apart, and there continues to be no evidence that any animals at the market was infected with the virus.

Is it possible that Quammen, along with his New York Times editors, did not know this? I don’t think so, but they can correct me if I am wrong. And if they did know, then they deliberately left out critical information that would have disrupted Quammen’s narrative and upset his “priors,” which are clearly operating at full strength at this point in his article.

But it gets worse still. Very near the end of the piece, Quammen mentions for the first time a grant proposal, known as DEFUSE, that several of the major players—Shi Zhengli, Peter Daszak, Linfa Wang, along with coronavirus expert Ralph Baric at the University of North Carolina—submitted to the military research agency DARPA in 2018. It was not funded, but many have suspected that one of the labs—most likely the WIV—later carried out the experiments anyway, perhaps with funds from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Here is how Quammen describes it:

“A more encompassing and emollient phrase is research-related incident,’ preferred by Jamie Metzl and some other critics. That covers several possibilities, including the chance that misbegotten gain-of-function research, at the W.I.V. or the Wuhan C.D.C. or who knows where, yielded a dangerous new hybrid virus that escaped through a malfunctioning autoclave or an infected technician or grad student. (In support of this scenario, proponents point to a grant proposal known as DEFUSE — made by EcoHealth Alliance to a U.S. defense research agency in 2018, though never funded — for experiments that some critics construe as potentially dangerous gain-of-function research.)”

(Note that Quammen links to the DEFUSE proposal, but was he expecting any of his readers to look at it?)

Please read this paragraph over at least twice. I mentioned before that the furin cleavage site is considered an important piece of potential evidence that SARS-CoV-2 might have been genetically engineered in the Wuhan lab. What Quammen fails to mention—but what he knows full well, because I and others have pointed it out to him repeatedly—is that the DEFUSE proposal explicitly included plans to insert furin cleavage sites into SARS-like viruses. This fact is so well known among both “lab leakers” and “zoonati” that failure to mention it can only be seen a blatant attempt to mislead readers.

Having made a dishonest and misleading “case” that a natural origin for the pandemic is best supported by the evidence, Quammen concludes by partly psychologizing and partly philosophizing about why the public—which in both U.S. and international polls favors the lab origin hypothesis by about two-thirds—could be led astray from what the real “science” and real “scientists” are supposedly saying about Covid origins.

Quammen writes:

“So, what’s tilting the scales of popular opinion toward lab leak? The answer to that is not embedded deeply in the arcane data I’ve been skimming through here. What’s tilting the scales, it seems to me, is cynicism and narrative appeal.”

Having led his readers through a garden path, Quammen now concludes that it is our failure to trust scientists that has led so many people—including some scientists themselves, apparently—to lean lab leak. He goes on:

“The seeds of distrust have been growing in America’s civic garden, and the world’s, for a long time. More than 60 percent of Americans, according to polling within the past several years, still decline to believe that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, killed John F. Kennedy. Is that because people have read the Warren Commission report, found it unpersuasive and minutely scrutinized the “magic bullet” theory? No, it’s because they have learned to be distrustful, and because a conspiracy theory of any big event is more dramatic and satisfying than a small, stupid explanation, like the notion that a feckless loser could kill a president by hitting two out of three shots with a $13 rifle.”

Quammen finally lets the cat out of the bag: The lab origin hypothesis, as some have insisted all along, is a “conspiracy theory,” nothing more or less. (I won’t elaborate on the fact that a lot of reasonable scholars and others think the JFK assassination involve multiple actors, including some who have actually read the Warren Commission report.)

Known priors, and unknown priors.

Why has it all gone down this way? Quammen is right that we all have our priors, although my own have changed over time. I remember the first time, early in the pandemic, someone told me they thought a lab origin for the pandemic was likely. It was someone I respected a lot, and I thought he had gone a little crazy in this particular area. As time went on and I got involved in reporting on the issues, I moved to a position of neutrality. My main issue was the way journalists were handling the debate, how the reporting could be better, and why so many reporters had such strong priors (read biases.) Now, I am leaning lab leak pretty heavily, as new information has emerged over the past year or so.

I also tried to explore how the subject had become so politicized. I wrote:

“The politicization of the origins debate has greatly hurt the search for the truth, even though most everyone involved agrees that knowing the origins of this pandemic can help prevent the next one. If COVID-19 was caused by a lab-leak or other lab accident, those who have argued for stricter biosafety regulations — including an end to so-called ‘gain-of-function research’ that can make human pathogens even more dangerous — will have new arguments for making research safer. And if the virus jumped to humans from wild animals sold at a market, it will be more clear that the wildlife trade — which many scientists and journalists have warned about for decades — must be brought under control, not only by China but many other countries as well. Simply put, humanity cannot afford another pandemic, nor can it afford not to understand how the current one came about.”

But for the politicization to end and the real science to begin—something which in many ways has still not happened yet—we need honesty from both scientists and journalists. We need editors at the New York Times to realize when one of their writers is providing a dishonest propaganda piece disguised as a slick piece of journalism. And we need them, and all others involved in this debate, to take a close look at their own priors. Quammen is at least right about that, even if in this piece he has failed utterly to do it.

“Quammen has not disclosed that he is good friends with some of the researchers most suspected of collaborating on the research that might have led to a lab accident: Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, which funneled NIH funds to the Wuhan Institute of Virology; Shi Zhengli, the WIV’s famous “Bat Woman;" and Linfa Wang, a scientist in Singapore and close collaborator with Shi.”

This is CRAZY. I read that story and though I’m inclined towards the lab leak theory, I thought it was … okay. But I would have read it VERY differently knowing that he’s friends with Daszak and Zhi. I had no idea.

Merci pour les éclairages. J’avoue que c’est difficile de s’y retrouver quand on y connaît rien. Et encore plus difficile de trouver des gens « neutres ». Bien souvent quand je regarde après les avoir lus leur « background » leurs activités antérieures et opinions, je n’arrive plus à leur accorder une confiance absolue .. ( journalistes ou scientifiques). Et même si je comprends l’anglais, certaines subtilités m’échappent également