Will a new president sort out the American Museum of Natural History's chronic #MeToo issues and make it a fair place to work?

Under outgoing president Ellen Futter, AMNH had a long history of fumbles when it came to sexual harassment. Her legacy includes chronic employee dissatisfaction, which led to a successful union drive

On April 3, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City will get a new president. Sean Decatur, currently president of Kenyon College in Ohio, will take over from Ellen Futter, who has been in the post for 30 years. On the surface, at least, this represents a major change of leadership: Decatur is a Black man, whereas Futter is a white woman; Decatur is a scientist and educator, while Futter is a corporate lawyer who climbed the business ladder to become a director of JPMorgan Chase and ConEd; Decatur leaves Kenyon with a generally positive record, whereas Futter is departing from AMNH with a decidedly mixed legacy. Indeed, in the minds of some museum staff, she represents the worst of the cultural corporate mentality.

Decatur has got just three months to get ready to deal with the messes that Futter has left behind. He will face two main issues: A chronic failure to deal with ongoing issues of sexual misconduct at the museum, mostly at the hands of senior museum staff; and tendentious contract negotiations with the museum’s employees, most of whom voted to unionize last May after years of shamefully poor wages and working conditions. As an indication of how dissatisfied museum staff were with Futter and the AMNH administration, the vote to unionize was 85% in favor, only 15% against.

As a journalist based in the New York City area for the last dozen years, I have gotten to know many people at the museum, both scientists and support staff; and, while I was still at Science magazine, the AMNH was the focus of one my most complicated and dramatic investigations, involving a serial sexual harasser who ended up being forced to resign. These experiences have given me a certain vantage point from which to comment on the museum’s issues, which I propose to do now.

Three #MeToo cases, all badly handled

Talk to museum staff, especially of course women, and they will tell you sexual misconduct has been a problem at the museum for decades. But a turning point came in late 2015, when the museum—after letting human origins curator Brian Richmond off the hook for alleged sexual assault during two bogus “investigations”—finally brought in a professional outside team to conduct a serious inquiry. But this was far from an example of the museum doing the right thing. Rather, the impetus for the third and final investigation of Richmond was the museum learning that Science, with me as the reporter, was planning to publish the accusations of a research assistant who worked with Richmond, along with students who had been the subjects of his unwanted advances over a number of years.

The story was published in February 2016. At the end of that year, the museum announced that Richmond would be resigning, although he was still given a full year’s severance pay as part of a settlement. In the wake of this scandal, the museum promised new anti-harassment regulations, training for its staff, and the other usual steps that institutions take when its protection of employees or students is found to be wanting.

But it would be nearly four more years before the museum would fire another serial abuser, notorious for bullying and sexual harassment, despite a long history of complaints dating back a number of years. This curator, Mark Siddall—a leading expert on leeches—was terminated in late September 2020, several weeks after I began reporting the allegations on social media and my blog. My sources at the museum told me that the museum administration had been well aware of Siddall’s behavior for a number of years, but had refused to act (the New York Times story on Siddall’s firing confirmed that as well, providing additional details of his victimizing conduct.)

In a series of harassing emails to me after his firing, and in an affidavit he provided the plaintiff in an unrelated defamation lawsuit, Siddall blamed me and my reporting for his downfall, claiming that the museum provost had no choice but to act once the accusations against him—which he continues to deny—became public. I do not know if this is true or not, but I can state with confidence that it would be hard to find anyone at the museum who misses him.

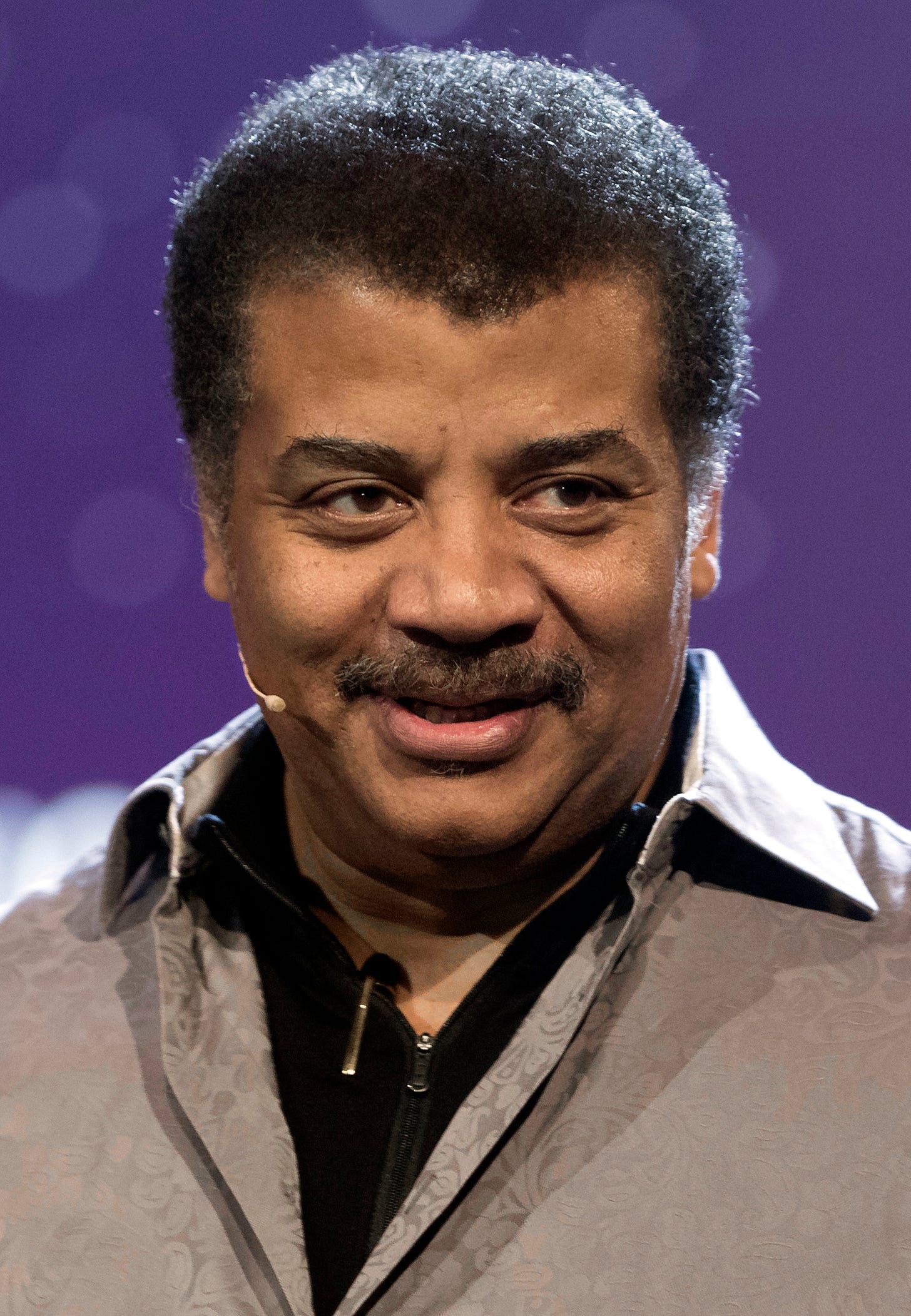

But in between the Richmond case, which got little media coverage other than my Science story (the New York Times knew all about it but failed to cover this scandal at a major New York institution), and the Siddall case, which did get some limited media attention, the AMNH managed to protect and retain one of its brightest stars: Astrophysicist and TV host Neil deGrasse Tyson. The credit for this story goes mostly to former BuzzFeed reporter Azeen Ghorayshi, who led the way with #MeToo reporting some three years before the Harvey Weinstein revelations. (I recently wrote about the pathbreaking role that science journalists like Azeen played in the earlier days of the #MeToo movement, even if they were not the ones to get the Pulitzer Prizes for their efforts.)

Tyson had originally been accused of raping a fellow student in the 1980s, yet it was convenient to ignore or disbelieve her. But Azeen talked to three other women who testified that Tyson had harassed them, and related their accounts in detail in a December 2018 story for BuzzFeed. The allegations led to three investigations, one each by Fox and NatGeo, who sponsored his TV programs, and also by the museum. The upshot was that Tyson kept all of his jobs; and, in an amazing lack of transparency, none of the three institutions would publicly reveal the results of their inquiries. In other words, we don’t know whether Tyson was found guilty or innocent, just that he suffered no consequences for whatever he might have done.

Tyson himself, in a March 2020 interview with the Daily Beast, was noticeably evasive about that, even as he defended himself from the charges (earlier Tyson had denied the allegations in a detailed Facebook post.)

Among those kept in the dark were the museum’s own employees, who, unlike in the lower profile Richmond and Siddall cases, never got to know whether a scientist they had worked with in the past—and would have to continue working with in the future—was a possible danger to women. As for the new guidelines and training the museum adopted in the wake of these scandals, they are widely considered a joke by most museum employees.

Many say that Futter, a woman who worked her way up the corporate ladder (and who was earning at least $1.2 million in compensation as she prepared to leave the AMNH, according to IRS records), proceeded to turn her back on other women who lacked her power and ability to avoid sexual harassment and violence.

“They should be ashamed” — AMNH votes to unionize

The American Museum of Natural History is certainly not the only institution of its kind where employees are underpaid, overworked, and under-appreciated. Indeed, over the past few years, a unionizing drive has swept the United States, as museum workers have started refusing to sacrifice their lives and wellbeing to art, science, or any other lofty endeavor—especially when those running the museums, like Futter, are bringing in huge salaries and other forms of compensation. The storied institutions that have unionized include the AMNH, the Whitney Museum and the Guggenheim in New York City, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (I learned recently, to my delight, that the workers at our local village public library were also organizing a union.)

A major impetus to organizing at AMNH and other museums came with the pandemic, which gave museum administrations a great excuse to downsize, lay off workers, and cut the pay of those who remained. At the AMNH, these anti-worker moves were particularly resented, given the years of poor treatment long before Covid-19, and also given the Futter administration’s cruel policy of restoring temporary pay cuts to museum executives while failing to do the same for museum staff.

Museum staff I know have told me many times how hard it is to live in New York City on AMNH salaries. So it’s no surprise that, last May, AMNH workers voted overwhelmingly to join Local 1559 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME.) But doing so still took considerable courage: In a series of emails and other communications, the museum administration did all it could to dissuade employees from voting yes, using union-busting tactics honed by the professional law firms the museum hired to do the job. And one very active union organizer, anthropologist Jacklyn Lacey, was fired for her efforts, although she is now fighting to get her job back.

But voting in the union is one thing, and negotiating a contract is another. Christine LeBeau, president of Local 1559, told me that there are two contract negotiations in progress, one with new union members and the other with staff who were already members of the local (the latter group has been working without a new contract for more than a year.) Meanwhile, the museum is refusing to include students at the AMNH’s Richard Gilder Graduate School in the bargaining unit, despite their NLRB-sanctioned participation in the union vote; hopefully museum officials are paying attention to the victory of grad students and other staff at the University of California, who just won major pay increases and other benefits after a major, unified strike in the entire UC system.

It remains to be seen whether Futter will negotiate in enough good faith to arrive at a fair contract with museum employees, or if the talks will drag on until Decatur takes over. If they do, the incoming president will be immediately tested on the question everyone at the museum is now asking: Will Decatur be an agent for change, or for the same old, same old?