Is the wet market hypothesis for Covid origins a house of cards? A new report prepared for WHO finds the data it relies on is biased and incomplete.

A 194 page analysis by Gilles Demaneuf of DRASTIC and the "Paris Group" is the most detailed analysis yet of China's highly skewed reporting of the earliest Covid cases.

If you rely primarily on major media outlets for your news, you might think that there is strong scientific evidence for the so-called zoonotic spillover hypothesis for Covid-19 origins, and that the lab or research related origin hypothesis has little scientific support. However, as I have discussed in numerous previous posts on “Words for the Wise,” that is not actually the case. Neither of the two main competing hypotheses for how this killer pandemic got started has direct evidence to support it, only circumstantial. Until or unless such direct evidence emerges, it is extremely important to engage in continuing evaluation of that circumstantial evidence, and—most important of all—to continue to investigate the question.

Doing so, however, has been an uphill battle, largely because there are vested interests in the outcome, including among a small group of scientists who have staked their reputations on the zoonosis hypothesis being correct. Nevertheless, most efforts to suppress the debate over Covid origins have failed, in large part because many people want to know the answer—and they realize that our ability to prevent future pandemics depends on knowing.

Until recently, reporting that challenges the dominant zoonosis narrative has been carried out mostly by independent journalists and investigators, writing for publications mostly on the left or the right of the political spectrum. The mainstream, so-called “liberal” media, including the New York Times and leading science publications like Science and Nature, has been missing in action for most of the pandemic. These and other mainstream publications have carried out little to no investigative reporting into Covid origins, a major journalistic fail.

In recent months, one major American media outlet has stepped away from the pack and begun to present information that challenges the dominant market origin hypothesis: The Washington Post. Last November, the paper published an important editorial entitled “Wuhan’s early Covid cases are a mystery. What is China hiding?” The piece featured investigative work by Gilles Demaneuf, a member of DRASTIC and the “Paris Group,” two organizations that have carried a lot of the weight digging up information relevant to the origins debate. Many of their sources are from China itself, thanks to members fluent in the language and able to negotiate the intricacies of Chinese publications and public health documents, many largely hidden even from the Chinese themselves.

In that first piece, the Post described in some detail the findings by Demaneuf and DRASTIC that China had not reported all the early cases it knew about to WHO:

“The research group DRASTIC, which has been probing the origins of the virus, has now found evidence that… by the end of February 2020, China had identified as many as 260 cases from the previous December. Yet China reported to the World Health Organization a year later — in early 2021 — that there were only 174 cases that December. This raises important and still unanswered questions: Who were these early cases? How did they get sick? Why were they not reported to the WHO?”

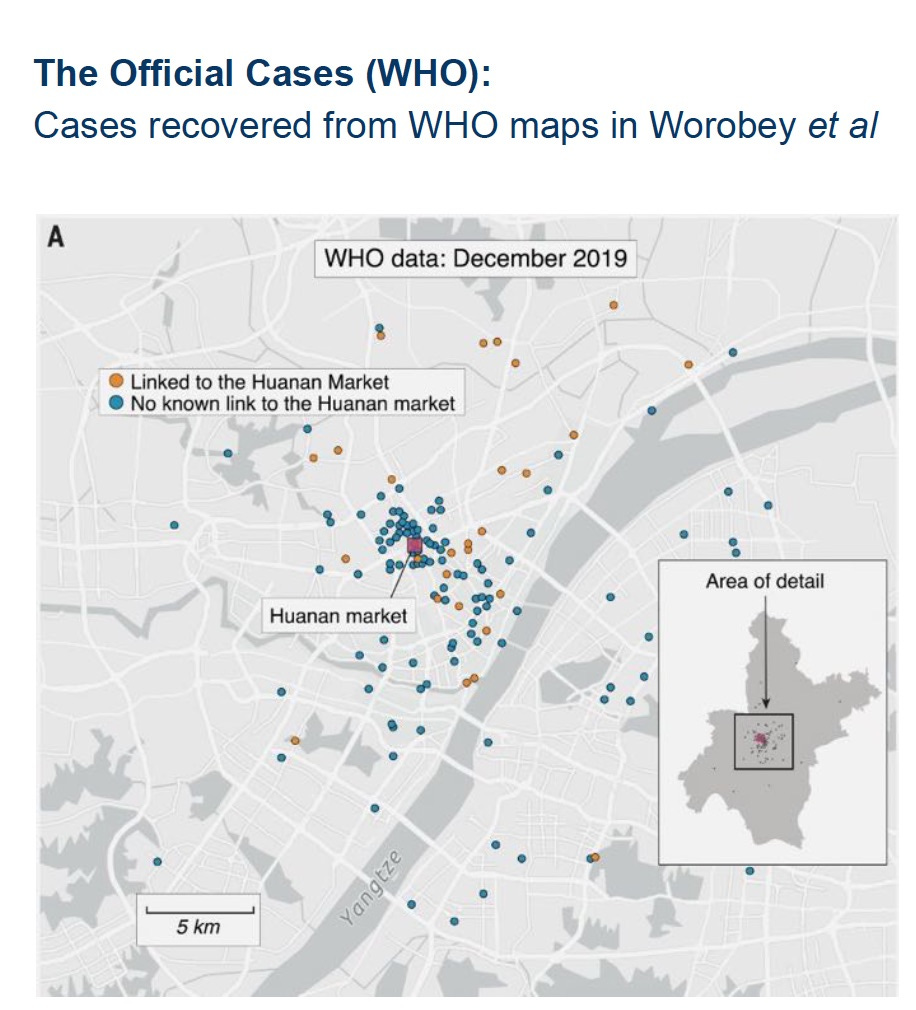

Why is this important? Because what zoonosis proponents consider their most important evidence relies almost entirely on this data reported to WHO. That evidence was laid out in two papers published in Science last year, Worobey et al. and Pekar et al.—two papers that received breaking news coverage in the New York Times when they were first released in preprint form, and in media outlets around the world. These studies relied on the data reported to WHO for spatial and genetic analyses that the authors claimed pinpointed the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan as the “epicenter” of the pandemic. (More recent claims that raccoon dogs might have been the intermediate host present at the market have largely collapsed upon closer analysis.)

The weight that zoonosis proponents have given to the Worobey and Pekar studies cannot be exaggerated. In essence, the entire natural origins hypothesis depends upon these studies and their conclusions being correct. As one of their coauthors Tweeted at the time they were published:

Despite such claims that these studies answered the “fundamental question” of Covid-19 origins, a number of research groups have challenged both the data and the analysis of the Worobey and Pekar papers. These critiques range from clear indications of “ascertainment bias” created by concentrating almost entirely on patients from the seafood market, to mathematical errors in the analyses, and include doubts about whether the much heralded “double spillover” from animals to humans ever actually took place.

Unfortunately, other than myself and the British science journalist Matt Ridley, I am not aware of any other reporter or publication that has focused closely on these counter-arguments or tried to take them seriously as part of the scientific process. (They have been widely discussed on social media, however.) Last fall I went over some of these critiques fairly briefly in a post on this newsletter; several of them have now been published in peer-reviewed journals, and I am planning a more detailed examination of them sometime soon.

Equally unfortunately, as far as I am aware, no media outlet other than the Post has featured in detail the work of Demaneuf, DRASTIC, and the Paris Group examining the data that underlies these strong claims. (If that statement turns out to be wrong I will correct it.) This week, the Post has gone one better, publishing another editorial featuring Demaneuf’s work, and linking to a 194-page report on the earliest Covid cases which he has now submitted to WHO’s SAGO, the Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens.

It’s important to note that both of these pieces in the Post were published as editorials, rather than reports by the paper’s journalists, which in many ways is symptomatic of the problem; I will discuss the media’s role at the end of this post.

The new report is dense, detailed, and very impressive in its scope. Demaneuf spent nine months preparing it; while it would be great if everyone would spend some time reading it, that is unlikely to happen other than in the case of diehard followers of the debate. So in what follows, I will try to do justice to this major investigative work with a summary and commentary—sort of a CliffsNotes version of something I had nothing to do with writing or preparing.

I am grateful to Gilles Demaneuf for bringing this report to my attention and generously allowing me to borrow a number of its graphics. Gilles has Tweeted his own thread about the work, highlighting what he thinks are the most important points, which you can find here. One of his key criticisms concerns the kind of “armchair epidemiology” with which Worobey and others treated incomplete and biased data, and then insisted that they had essentially proven the zoonotic spillover hypothesis. He hopes this so-called “p-hacking,” designed to arrive at a preconceived result, will come to an end.

Pour yourself a cup of coffee or a stiff drink, and follow along.

Let’s start by hitting some of the highlights of the report, and then we will go into some detail about them. What follows is based on Demaneuf’s own summary of the report.

— Chinese officials knew that the pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, was contagious, that is capable of human-to-human transmission, several weeks before they made that known to experts around the world. Failure to share that knowledge impeded the early response to the pandemic and probably greatly accelerated its worldwide spread.

— Many if not most of the early cases of Covid-19 were mahjong players at the Huanan Seafood Market, which was a major social gathering place for elderly residents of the area as well as employees of the market after they got off work. The mahjong rooms, which were semi-illicit and located near wildlife stalls, were very near toilets as well.

— By 2019 the wildlife trade in China, and especially in Wuhan, was not concentrated in the market stalls but had moved to underground supply and distribution channels.

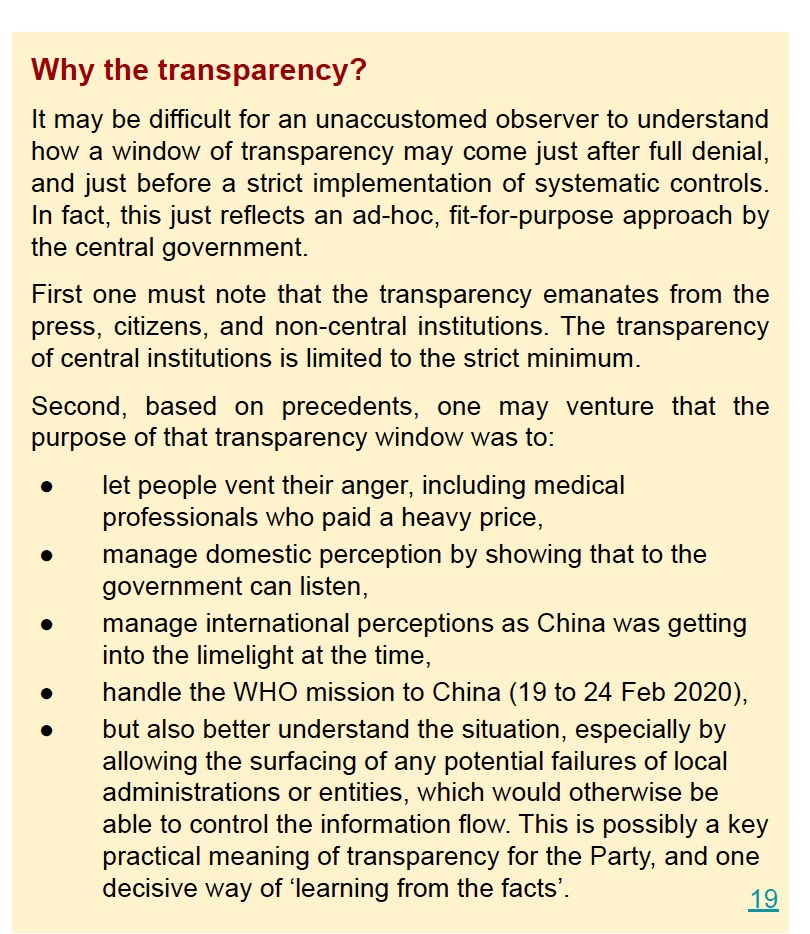

— In the earliest days of the outbreak, Chinese officials went through four stages of reaction: Emergency, Denial, Transparency, and “Control Recovery.” Only during the relatively brief transparency period was it possible for public health workers to collect data that could be used to retrospectively trace the earliest cases.

— The Chinese CDC had virtually no power or authority to engage in independent investigation of the pandemic; everything it was allowed to do was controlled by higher authority.

— Chinese authorities took numerous measures to prevent the leading hospitals in Wuhan from reporting the cases they were seeing as the outbreak began to rage. As a result, much early data was lost.

— The reporting that did take place came mostly from major, top-tier hospitals in Wuhan located along the Yangtze River. But most victims of the outbreak were poor and could not afford those hospitals. Again, critical data was lost.

— The only attempts at tracing retrospectively, and thus recreating the earliest cases, were made during a brief window in February 2020, amounting to about four weeks, during the “transparency” period. Even so, the cases reported to WHO were “rolled back” to about February 14, ensuring that the data available to researchers (including of course the Worobey/Pekar teams) would be biased and incomplete.

Into the weeds.

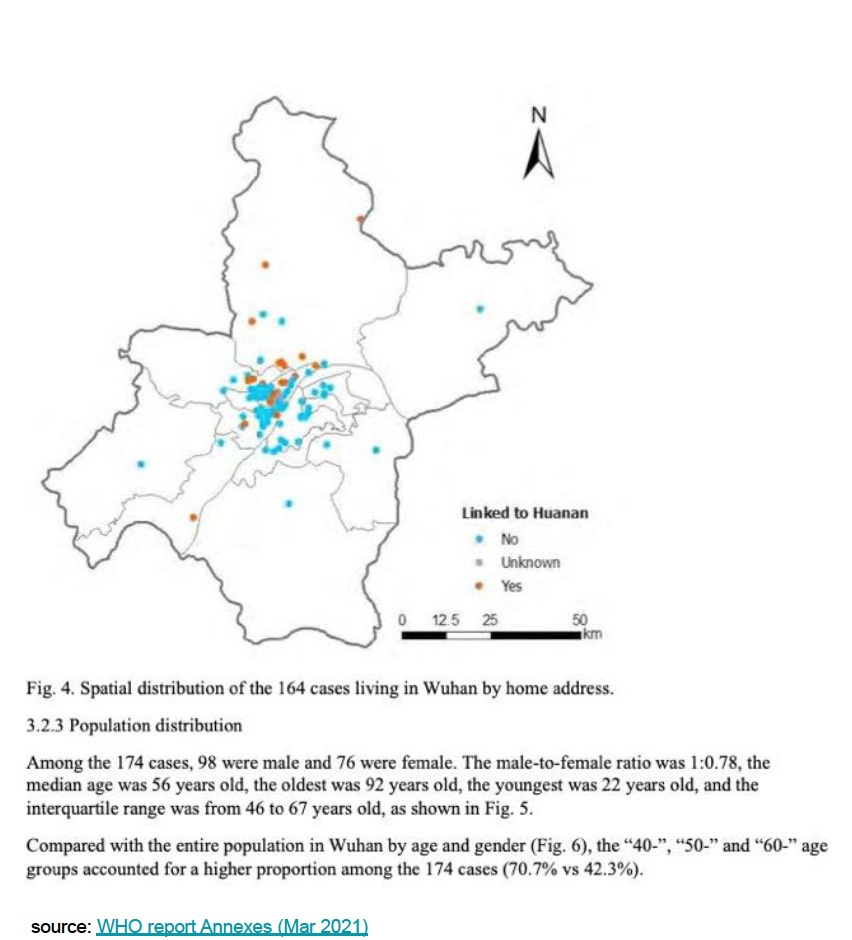

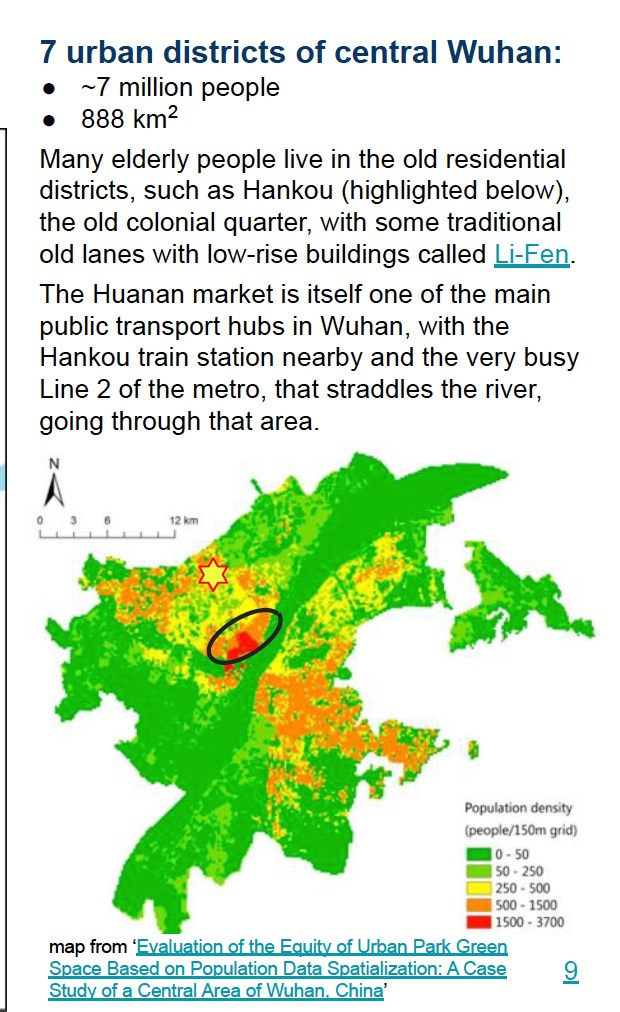

As the report points out, a total of 174 cases from December 2019 were reported to WHO by Chinese authorities. All but ten of these patients lived in Wuhan. Some scientists and investigators have long pointed out that the earliest cases were not linked to the Huanan Seafood Market, although there is little doubt that as December progressed a significant number of patients did have such links. The question has always been why: Because of a zoonotic spillover at the market, or because the market served as a super-spreader site for a virus that had already established itself in the city? As Demaneuf highlights, the Huanan market was a major transportation hub, near a major train station and through which the riverside Line 2 of the Metro passes:

See also:

Demaneuf goes on to look in detail at what we know about these 2019 cases, in what he calls “A play in four acts.”

In Act One, which began about December 30, 2019, Chinese officials went on an emergency footing to identify current cases of a “pneumonia of unknown origin,” most of which were patients at the Wuhan Central Hospital. By the next day, these patients and more had been transferred to Jin Yin-tan Hospital, which had a special “negative pressure” ward designed for highly infectious patients. Already, no later than December 27, a private company had partially sequenced the virus and found it had a high homology to SARS-1, which had caused the SARS outbreak nearly 20 years earlier.

Although not all the cases were linked to the Huanan market, by January 1, 2020, the Wuhan Health Commission had made a link to the market as a criterion for reporting the new disease. There was no attempt at that time to trace earlier cases as part of a retrospective reporting effort that might have helped pinpoint the pandemic’s origins.

In Act Two, what Demaneuf calls the “Denial” phase, Chinese officials appear to have begun suppressing data. For example, the reported number of cases never increased between January 5 and January 17; it actually decreased from 59 to 41 cases. Only when officials admitted that human to human transmission was taking place did the number of cases begin to rise again; Demaneuf suggests that the denial “is kept until 22 Jan, when it simply becomes impossible to keep up, as the market had been closed for too long while cases had already started to pop up abroad.”

During Act Three, there was a period of “brief transparency,” when public health officials and media were allowed to do their job to some extent. Demaneuf’s analysis of this period and the reasons for it make very interesting reading:

The “transparency” window closed at the end of February 2020, after a series of gag orders—including one from Xi Jinping himself—were again issued. Critically, the 174 cases from 2019 reported to WHO, and which Worobey and Pekar relied upon for their own analyses—and which Demaneuf earlier found did not include dozens of known cases from that period and were also missing critical information such as age, occupation, date of infection, etc.)—were compiled from that transparency period, and from hospital records alone. After that, Chinese officials entered what Demaneuf calls the “Control Recovery” mode—a lockdown on information, and Act Four of the play—which has basically been in effect ever since.

As Demaneuf comments:

“Most people think that the retrospective search was done over months, if not a full year, before the WHO was handed over 174 confirmed + diagnosed cases for Dec 2019 (164 cases for Wuhan). This could not be more wrong!”

To make matters worse, and as the earlier work by Demaneuf and his colleagues showed (reported in the Washington Post last November, and derived from peer-reviewed papers by Chinese researchers) Chinese officials at the end of February 2020 knew about 257 confirmed cases, not just 174. Why were more than 80 cases not reported? Were they typical of those reported, or did they differ in some critical way? The integrity of the Worobey and Pekar papers leans heavily on those questions.

Holes in the data, and biased interpretations of the data, continue to abound.

As mentioned above, Demaneuf engaged in a detailed analysis of China’s healthcare system, which has three tiers: Small and local primary care facilities, larger district “secondary hospitals,” and major municipal hospitals. The reporting of early cases was restricted almost entirely to the last category, thus missing many patients who might not have needed longer term hospitalization, or who may have died and their deaths attributed to other unknown causes.

Any biases in the data here would have been exacerbated by the fact that simultaneous with the Covid-19 outbreak was an unusually active winter flu season.

In Wuhan, these large, top tier hospitals are concentrated in the center of the city, on the seafood market side of the Yangtze River. This could have contributed heavily to the “ascertainment bias” pointed out by a number of researchers, and which could easily have led to the focus on the Huanan Seafood Market as a possible source of the pandemic rather than a super-spreader site.

And as noted above, this could have biased the data against patients who were poor and could not afford to go to the main hospitals. Although China is supposedly still a “Communist” country, its supposed universal health care is hardly that. Citizens still have to pay a significant portion of medical bills out of their own pockets. For a top tier hospital, that could mean the equivalent of at least six months’ salary and often much more.

Demaneuf summarized the importance of these points in this panel:

In one of the most important sections of the report, Demaneuf focuses on what might have been a key confounding factor that biased the published literature, especially the Worobey and Pekar papers, towards a market origin: The presence of the mahjong players in the market, and the proximity of their playing rooms to the toilets in the same part of the market that produced the most Covid cases. (Many viral samples were recovered from these very toilets.)

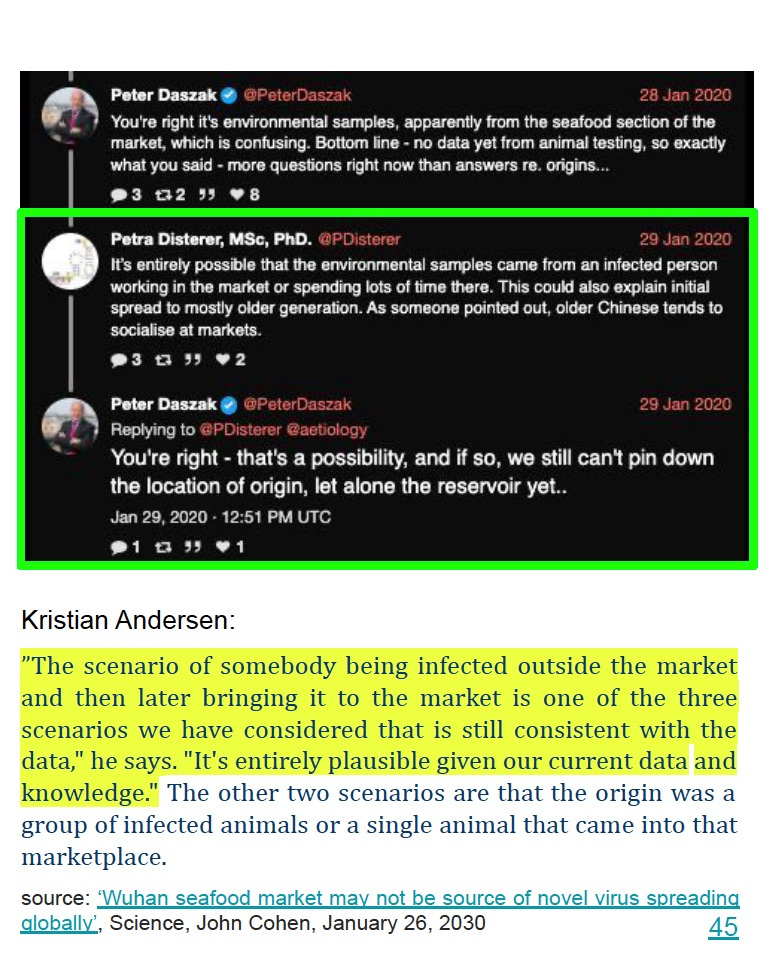

Indeed, the possibility of that kind of scenario was readily admitted in late January 2020 by scientists who now are fierce opponents of anything other than the market origin hypothesis, as Demaneuf points out in the following graphic:

Demaneuf cites a number of sources, and quotes a number of colorful descriptions, about the mahjong rooms, which are often frequented by middle-aged market employees and local retirees. They would often gather after the market closed in smoky, badly ventilated spaces.

The mahjong rooms are not mentioned in the Worobey/Pekar papers, nor in WHO reports, as Demaneuf points out:

I’m going to skip over the rest of the report pretty lightly, which gets even more into the weeds of obstacles to proper reporting of Covid cases, due to administrative obstruction and the bureaucratic obstacles typical of an authoritarian government like that of China (although not entirely unknown in even the most “democratic” countries.) One very important bias that resulted from these administrative obstructions, however, was the requirement beginning December 31, 2019, that cases had to have a link to the seafood market to be reported. That this would have resulted in “ascertainment bias” in any subsequent analysis of the data can hardly be doubted.

And in one of the last sections of the report, Demaneuf lays out “the crucial importance of retrospective reporting” to any reconstruction of Covid origins—which would have depended on a serious investigation of previous cases. But once that “transparency window” closed, there was little hope of such a reconstruction, and thus little hope that epidemiology could do the job it was meant to do in tracing the origins of the outbreak. Moreover, there was little hope that evidence of cases earlier than December 2019—for which there are considerable indications—could be added to the overall database that scientists could work with. We are still living with the consequences.

The (largely disappointing) role of the media.

As I suggested above, there is good news and bad news on the topic of media coverage of the Covid origins debate. The good news is that the Post has helped bring the important investigations outlined above to the general public, even if its editorial gives few details about this new report. For that, those interested will have to either read it themselves, or hope that the media—other than “Words for the Wise,” that is—will eventually report on it in detail.

As I mentioned, even the Post has not really reported on it; its news team was not involved. Rather, it has used its editorial space to link to Demaneuf’s work and describe it briefly. That is better than nothing, but we need major publications with big reporting budgets to get involved in reporting on Covid origins. That has been sorely lacking.

Certainly, there is no excuse for not covering this new report, which has been submitted to SAGO and hopefully will become part of its deliberations. That is especially true because the report makes no comments at all about the Covid origins debate, and is not at all a piece of advocacy for the lab origin hypothesis or any other scenario. It is a sober and powerful look at the evidence being used in that discussion; for that reason alone, journalists and scientists alike have a solemn responsibility to examine it closely.

For many journalists, that would mean changing their habits and their biases. I have discussed many times, in this newsletter and elsewhere, the unfortunate, desultory marriage of our “best and brightest” science journalists to one side of an unresolved debate, to the point of dishonor and dishonesty.

Meanwhile, as evidenced by the nine months Gilles Demaneuf and his colleagues spent on producing this report, some investigators actually take this pandemic and the question of its origins seriously. It’s far past time to see that example catch on among some other journalists who, lately, have not deserved to be identified with that noble profession.

Great stuff. Just one comment re the media: deserving of mention is the important work done by The Australian newspaper, and in particular their star investigative journalist Sharri Markson, leading to her book What Really Happened in Wuhan - and still ongoing.

Thanks for summarizing the most important parts of the lengthy report by Gilles Demaneuf.